In November 1925, a new employee of the National Life & Accident Insurance Co. drove his “trick lizzie,” as he described his car, from Chicago to Nashville. It was a long trip for the man, his wife and two daughters. By the time they arrived, they were “bespattered with mud,” according to a Nashville Tennessean article about the trip.

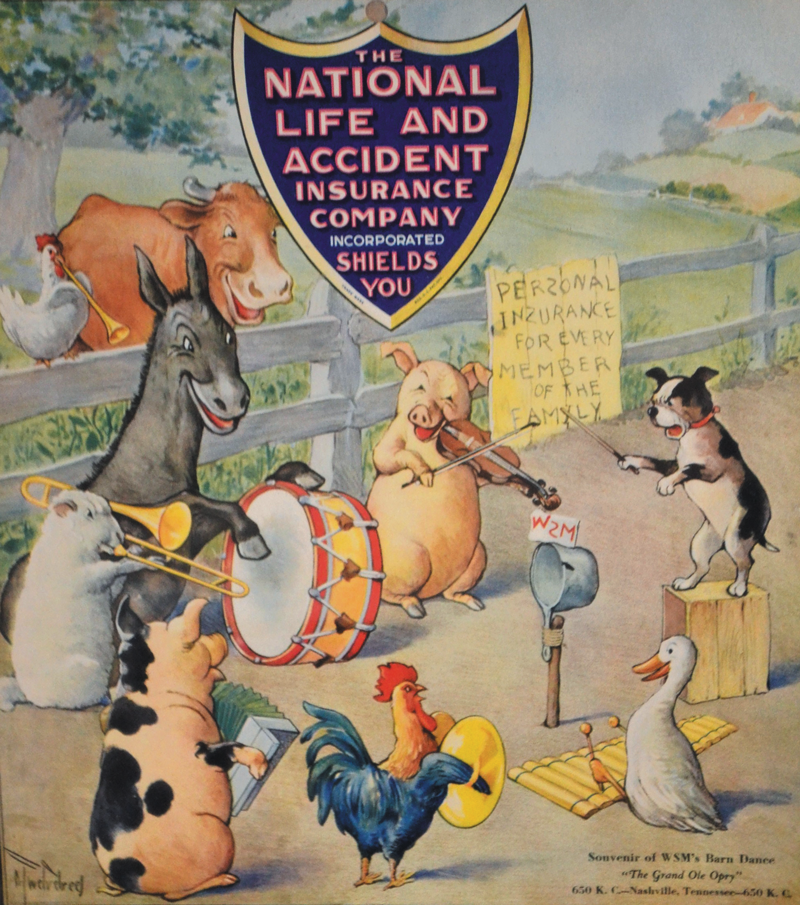

The man was George Hay. He had been hired by National Life to direct its new radio station, WSM, whose call letters stood for “We Shield Millions.”

Hay was already a celebrity. A one-time reporter for the Memphis Commercial Appeal, he tried his hand at radio when that newspaper started a station called WMC. Hay was eventually named, by survey, the most popular radio announcer in the country.

That honor earned him a job with station WLS in Chicago (a Sears, Roebuck & Company-owned station whose acronym stood for “World’s Largest Store”). However, Hay didn’t take to Chicago too well and jumped at the opportunity to run Nashville’s new radio station.

“I’m tickled to death to be back in Dixie,” he told a reporter when he got to Tennessee.

Hay, nicknamed the “Solemn Old Judge,” didn’t waste any time when he got to town. Within a day of his arrival, he met the employees of WSM and the executives at the National Life & Accident Insurance Co.

Hay especially excited Nashville’s morning newspaper, which published three stories about the new WSM director the week he arrived. One of Hay’s trademarks in Memphis, the paper reported, was an old steamboat whistle he called a “railroad whistle” while he was on the air in Chicago. “He (Hay) originated his own particular style of announcing, refusing to conform to stereotype ideas, and is capable of handling any type program from the most classic to the jazziest,” the Tennessean reported.

However, we do not remember Hay for his love of classical or jazz music.

About three weeks after his arrival, a 77-year-old fiddle player from Wilson County named Uncle Jimmy Thompson made an unscheduled two-hour appearance on WSM. Like another man who had played on WSM a few weeks earlier named Humphrey Bate, Thompson played a type of music then known as “old-timey,” or “hillbilly” — the kind of music that featured fiddles, harmonicas and guitars.

After Thompson played, the response from the public in the way of telegrams, letters and phone calls was overwhelming. Hay brought Thompson in to play again and again, and listeners loved it. For a few weeks, Hay wrestled with National Life about what to do.

Then, around Christmas, WSM announced it would be devoting a regular Saturday night show to what its newsletter described as “old familiar tunes.” The show, which for two years was known simply as the Barn Dance, featured performers like Thompson, Bate, an African-American harmonica player from Smith County named Deford Bailey and a well-known vaudeville performer from Rutherford County named Uncle Dave Macon.

WSM had a “clear channel” signal, which meant it could be heard a lot farther away than other stations, especially at night. After the show debuted, some of the fan mail WSM received came from as far away as the West Coast.

“Last night an old Tennessee hillbilly out in Western Oregon was giving the dial a final twist about 10:15 Pacific Time when he hit banjos like they never have,” said one letter. “The wife dropped her knitting and moved over closer to the old (radio) set.”

Gertrude Bellringer of Atlantic City, N.J., said the music she heard on WSM was “the best I have got on the air for some time. Your city must be wonderful to produce such old-time music. It is so different than what we folks in the East hear.”

Hay was a showman who had a way of giving listeners the impression that the show was being broadcast from a barn and that its performers were farmers. In fact, WSM’s studios were located on the fifth floor of a stately downtown office building. Many of the musicians wore coat and tie as they played and sang.

Band leader Humphrey Bate, for instance, was a Vanderbilt-trained medical doctor. When he and his band first appeared on the Barn Dance, they were known as Humphrey Bate and the Castalian Springs Barn Dance Orchestra. Before long, Hay renamed the band the Possum Hunters.

Here is an anecdote I dug up a few years ago when I researched and wrote a book called “Fortunes, Fiddles and Fried Chicken”: Six months after it started, WSM announced the cancellation of the Barn Dance. “WSM will continue the barn dances through the month of May, but beginning June 1 will probably discontinue the old-time music for the summer, unless the public indicates the desire to have it continued throughout the hot weather,” the Nashville Banner reported on May 9.

National Life executives reversed that decision a couple of weeks later after Barn Dance fan letters came in from as far away as California. “The proportion is about fifty to one,” the Banner reported, although the article implied that most of the letters against the Barn Dance were written locally.

About a year after the show went on the air, Hay started calling the show “The Grand Ole Opry,” a name he came up with spontaneously when he compared it to another popular show at the time called “The Grand Opera.” “For the last hour, we have been listening to music taken largely from grand opera and the classics,” he said. “We now present our own Grand Ole Opry.”

It took a couple of decades for the Opry and “country” music to evolve into an industry. The real turning point was most likely during World War II, when several Grand Ole Opry stars went on tour, visiting U.S. military servicemen across the world. This trip reinforced the popularity of performers such as Minnie Pearl and Roy Acuff.

After the war, the publishing and recording of “country” music, as it became known, became a business in Nashville. The Grand Ole Opry continued its run and introduced a new generation of superstars, the biggest of which was Hank Williams Sr.

George Hay, who arrived in Nashville bespattered with mud in November 1925, is thus the originator of the art form today known as “country” music.