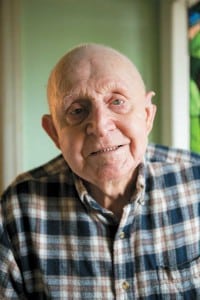

Rossville veteran R.H. Pulliam’s life is a story of survival, duty and determination.

Mr. R.H., as everyone knows him in Rossville, just celebrated his 92nd birthday. At home in the simple farmhouse he built in 1952 for him and his young wife, Patti, to begin their lives together, Rupert Harvey Pulliam Jr. recounts a birthday he’ll never forget.

You see, R.H. spent his 21st birthday as an injured prisoner of war in Germany. His story of patriotism and duty is not uncommon amongst the hundreds of thousands who valiantly fought for our country during World War II. His story of survival, on the other hand, is quite remarkable.

Two years after graduating from Collierville High School, R.H. joined the United States Army Air Force in April 1943.

Before enlisting, he spent his time working on his family’s farm and helping clear the first right-of-way for Chickasaw Electric Cooperative. “I learned how to use a cross-cut saw really quick,” says R.H. “There were four or five of us local boys. We cut the right-of-way by hand from Macon to Rossville in 1940 or so. I earned an Atwater Kent refrigerator for my work. Daddy paid me for it.”

Perhaps R.H. began to learn something about service to others that summer as he helped the newly formed Chickasaw Electric Cooperative get electricity to the farms and communities. His cousin, J.P. Pulliam, was a founding member of CEC in 1940, and his father, R.H. Pulliam Sr., served on the board of directors for many years.

Enlisting in the Army a short time later, R.H. knew he wanted to serve his country. “I joined the Army Air Force and trained to be a ball turret gunner on a B-24 bomber.”

The ball turret was an exposed Plexiglass bubble centered under the belly of the B-24, as described by the Army Air Force. Gunners had to be smaller in stature to fit in the sphere that housed two .50-caliber machine guns. Gunners revolved with the turret as they tracked enemy fighters.

Crews were assembled and trained together stateside at several bases scattered across the country before deploying to the European Theater. According to R.H., his training began in Nashville and continued, in succession, in Biloxi, Miss.; Denver, Colo.; Las Vegas, Nev.; and finally Herington, Kan.

“We picked up our plane in Herrington,” says R.H. “That was the plane we were shot down in.”

As the crew prepared to fly the plane to England, they realized their flight path would take them very close to the farm of R.H.’s parents in rural West Tennessee. However, they couldn’t tell anyone what their orders were, when they were leaving or where they were going.

But as the plane flew “low and slow” over the Pulliam farm, R.H.’s parents, R.H. Sr. and Sally, knew their son was on that plane. “Mother said we knocked leaves off the sycamore tree we were so close,” says R.H. “We flew down low, and I remember seeing my horse raring up in the backyard. I dropped a .50 caliber machine-gun bullet with a hankerchief tied to it like a parachute so they would know it was me.”

The bullet, retrieved and saved by his parents, is one of the few artifacts R.H. has from the war. It’s kept on a shelf not far from his brown recliner in the living room.

Arrriving as part of the 466th Bomb Group of the 787th Bomb Squadron flying out of Attlebridge, England, the crew readied for their first combat mission. The American Air Museum in Britain lists the crew members as Charles Bidgood, bombadier; Robert Boebel, co-pilot; John Bushing, top turrett gunner; Clem Ehmet, radio operator; Daniel Harris, pilot; Lyndle Newman, tail gunner; Rupert Pulliam, ball turrett gunner; Eldon Slager, right waist gunner; Thomas Styalinger, navigator; and Sam Wilkinson, left waist gunner.

It was on their fourth mission that R.H. and the rest of the crew experienced their first hit by enemy fire.

“We were hitting the airfield in Hanover, and they didn’t like that,” R.H. says. “They hit us with antiaircraft fire.”

R.H. recounts that as the plane was burning and going down, the crew knew they would have to bail out to survive. “We were shot down on April 8, 1944, which was Good Friday.”

“My ’chute burned up, so I helped clear out the other gunners. I didn’t think about hooking onto them,” recalls R.H. “The waist gunner got hung up on the plane and went down with the ship.”

“I went on up to the front, walking on the catwalk,” recounts R.H., holding his hands about 8 inches apart to describe the narrow beam at the center of the plane. “My feet slipped out from under me, and I fell a-straddle of it.” With the bomb bay doors open, he barely missed plunging to his death. Fortunately, he regained his balance and lost only his oxygen tank and mask.

“The pilot, co-pilot and radioman were still in the front,” R.H. remembers. “The pilot said, ‘We’ve got to bail out.’ The radioman, Ehmet, said, ‘Hook onto me.’ So I hooked my harness onto his strap, and out the bomb bay we went.” Though they escaped from the burning plane, they landed in enemy territory.

R.H. and Ehmet hit the ground hard with both of them on one parachute. Ehmet was able to escape to cover. R.H. suffered a broken leg and severe burns to his back and head where his parachute and oxygen mask had been.

“We landed in a field with some farmers out there,” R.H. says. “Since they only saw one parachute, they found me first and didn’t look for the radioman. They came over with pitch forks but didn’t do anything.”

“They came out in an open touring car and carried me to a hospital,” R.H. adds, but “they (the hospital) wouldn’t take me, so they carried me to another, and they wouldn’t take me. They carried me to a third, and they took me.”

Back home, R.H. was reported missing. It would be four months before the family learned he had survived and was a prisoner of war. He remained in the hospital in Hanover for several weeks as his burns slowly healed and the broken leg mended. He was transferred to another hospital that he recounts was run by British doctors who had been captured in North Africa. He was then transferred to a series of POW camps where food was scarce and soldiers survived on the bare minimum.

“We didn’t have enough to eat, but we had enough to live on,” R.H. says. “We got Red Cross packets with powdered milk, Spam and a pack of cigarettes. Before I went over there, I wouldn’t eat cabbage and didn’t care nothing about potatoes, but over there, that was all we had to eat.

“When they transferred us to the last POW camp in Barth, Germany, near the Baltic Sea, they did it with boxcars. There were 40 men to a car with no food or water, no nothing. We were on the train six days. The ones who were well enough and could walk, they put on the death march.”

R.H. narrowly missed being killed again after arriving in Barth. “The Royal Air Force raided the railroad we were in. We couldn’t run, so we just sat there,” he says. “We didn’t get hit.”

Thirteen months after he was taken prisoner, R.H. was among some 10,000 soldiers liberated from the Barth camp by Russian soldiers. “After the Russians, we got to Camp Lucky Strike (in France),” says R.H. about the beginning of his journey home.

The ship that would bring him home was aptly named the Liberty. Arriving home in August 1945, R.H. made a joyous reunion with his family and community to begin a new phase of his life that brought happiness and contentment. He launched what would become a 39-year career as a rural postal carrier in Rossville in 1948 and in May 1952 married Patti J. Frazier.

“Mother told me the first time she remembered Daddy was her first day of school at Rossville Elementary,” says Sara Pulliam, one of the Pulliams’ four children. “ I’m sure they met before that because they were raised less that five miles apart. She was in the first grade, and Daddy was in the third grade. He yelled at her to get out of the desk she was in because it was his.”

They were married for nearly 47 years when Patti passed away in 2009. Besides Sara, their children were Andrew, Diane and Roger. They also have seven grandchildren and two great-grandchildren.

Though R.H. has slowed down in recent years, he remains active in the community and serves on the Chickasaw Electric Cooperative board of directors. Following in his father’s footsteps, he joined the board in 1974.

“Chickasaw Electric Cooperative is very fortunate to have an individual such as Mr. R.H. Pulliam on our board of directors,” says CEC’s general manager, John Collins. “His knowledge and experience greatly aid our board as they make decisions that affect our members and employees. Mr. R.H. has served on the board for 41 years. He has witnessed and been a part of the many improvements and advancements that have enabled us to better serve our members.”

R.H. still enjoys his farm, doing a little fishing and, most of all, spending time with his family. Needless to say, each September birthday he celebrates is a much sweeter day than the one he spent in a POW camp when he turned 21.

Thank you for your service, R.H.!

Thank our veterans

Thank our veterans

As we celebrate Veterans Day on Nov. 11, keep in mind all those who have served and are serving to keep us safe. Share your memories and notes of appreciation with us on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram using #thankaTNvet.

Or send an email to [email protected] or letter to The Tennessee Magazine, Veterans, P.O. Box 100912, Nashville, TN 37204.

1 Comment

This is my grandfather. I am Roger Pulliam’s son. Thank you for this article, I would love to tell you other stories from the war that he hold me before he died.