Jim Ruth recalls transporting Freedom Riders during civil rights movement

Those born after the height of the civil rights movement of the 1960s have not lived in a world where races had to use separate facilities and sit in different areas of buses or where someone might not receive service at all if he or she were African-American. It’s mind-boggling to think that even two Supreme Court decisions didn’t end segregation in the South, but it’s true. Despite the fact that the decisions — 1946’s Irene Morgan v. Commonwealth of Virginia and 1960’s Boynton v. Virginia — found that segregated public buses were unconstitutional, the practice was still going strong in the Jim Crow South in 1961. Thus, hundreds of civil rights activists, black and white, undertook what became known as the Freedom Rides, interstate bus trips into the segregated South to challenge the lack of enforcement of those Supreme Court decisions.

Sadly but predictably, violence ensued. Freedom Riders were beaten by mobs, often with the full knowledge and tacit approval of local law enforcement, and buses were firebombed. On some occasions, the white participants of the rides received even more brutal beatings, likely because the members of the mobs viewed them as race traitors.

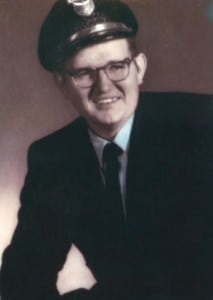

Because of all the violence, it was sometimes difficult to find bus drivers willing to shuttle the Freedom Riders. Perhaps they feared for their safety or didn’t agree with the cause — or both. But one Tennessee man didn’t think twice before saying yes when he was approached to drive a group of Freedom Riders from Nashville to Jackson, Miss. Jim Ruth of Brighton, a member of Southwest Tennessee Electric Membership Corporation, will tell anyone who asks that it was his job, adding, “If they were going to die, I was going to die with them.”

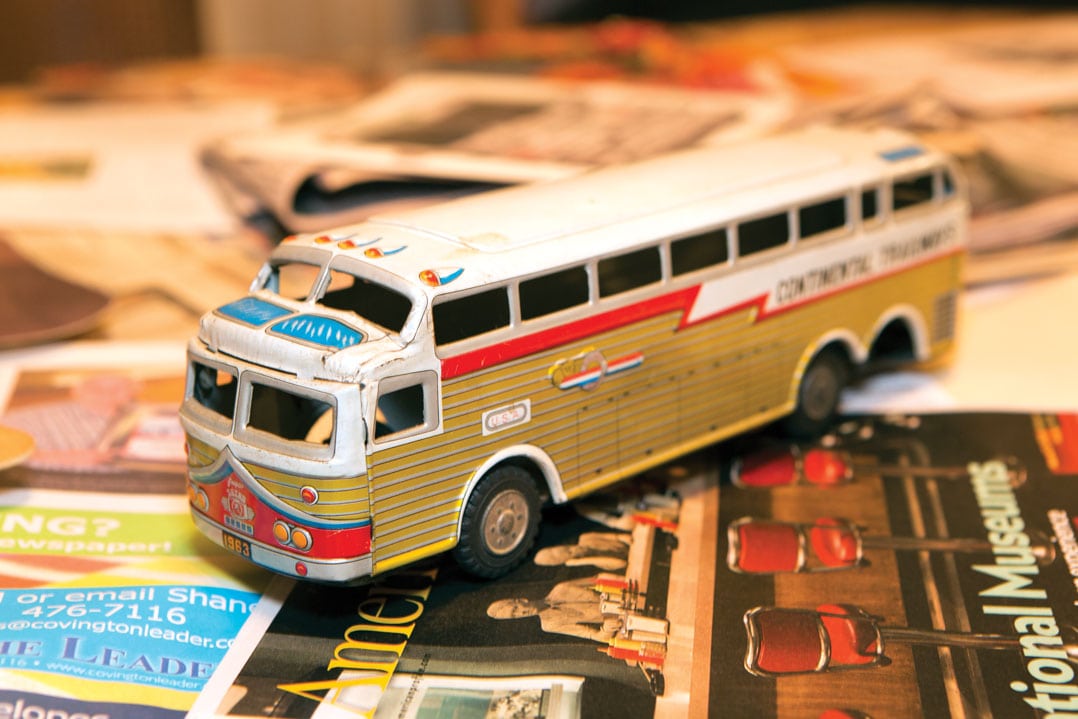

Ruth was in his early 20s and driving for Trailways when he was approached by a professor at Nashville’s A&I State University (now Tennessee State University) to take a group of student activists to Mississippi. Four other drivers had already turned down the request because they were scared to make the trip. But unlike some of the other Freedom Rides, the one that Ruth drove didn’t see any violence. He says that after leaving Nashville, they made a stop in Jackson, Tenn., where his parents brought him some shaving cream at the bus station; another in Memphis for gas; and the final one in Batesville, Miss., so he could get some coffee before they arrived in Jackson, Miss., where he dropped off the riders at a motel. Ruth gave them his phone number, and they called him when they were ready to return to Nashville.

“We made it just fine,” he says, “didn’t have any trouble.”

What Ruth didn’t know until later was that they were followed during the trip by a bodyguard. “I never saw him,” he says.

Ruth, who has been a widower for several years, is disabled, in part because of a bus crash in 1963 that left him unconscious for 19 days and partially paralyzed. He happened to be listening to the news out of Memphis a few years back when he heard of efforts to find the drivers who drove the buses for the Freedom Riders. Some phone calls later, he found himself in Nashville being honored by the NAACP for his important role in the struggle for civil rights for African-Americans.

“They treated me like a king,” Ruth says, smiling. “I’d never been honored like that. There were about 500 people there, and I got up and gave a speech in front of all of them.”

Ruth thinks very highly of the Freedom Riders, too: “They were the best group of people I ever hauled.”

He says it was nice to reconnect with the riders to whom he hadn’t talked since returning them to Nashville all those decades ago.

Ruth says that at the time he had no idea that what he was doing would be so important to history, though he’s proud of his decision to make that drive.

Since he was honored by the NAACP, he’s been interviewed several times, talked to lots of people about his experience and has seen his awards and story become parts of an exhibit at the Tennessee State Museum in Nashville.

“It was more important for me to give them to the state of Tennessee than for me to keep them,” he says.

If you would like to contact Jim Ruth please send an email to [email protected].