Revolutionary explorer, important in his time, died in debtor’s prison

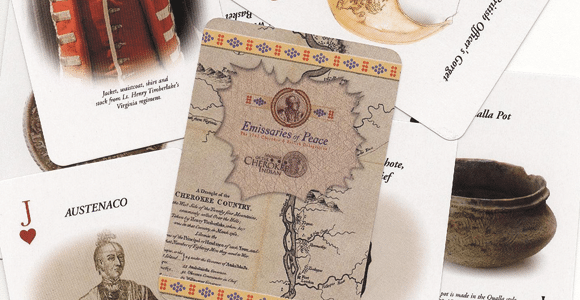

We all like to think that if we are diligent, undergo great ordeals in the service of our country and are involved in the monumental events of our time, we will be rewarded. But this was not true of Henry Timberlake. He risked his life to help bring an end to a war. He was one of the first people to document what Cherokee civilization was like before it was changed by Europeans. He took three Cherokee chiefs across the Atlantic Ocean to see King George III, one of the first times in world history that European royalty came face to face with Native Americans.

None of these things earned Timberlake wealth, comfort or even the gratitude of his country. He died in debtor’s prison and didn’t live to see his life’s work published.

Timberlake was a junior officer in the Virginia militia during the French and Indian War. In 1761, his regiment was building a fort in present-day Kingsport. To their surprise, a large force of Cherokee arrived and appealed for peace.

One of the Cherokee leaders, a chief called Ostenaco, asked the British commander for an officer to accompany him on a journey through Cherokee lands as proof that hostilities were over. Timberlake volunteered for that duty. He was accompanied by a sergeant named Thomas Sumter as well as an interpreter and a servant.

The journey started off as a disaster. Rather than travel overland with the large group of Cherokee, Timberlake opted to go by canoe. However, the Holston River was unusually low. He and his men had to drag their canoes and carry their provisions over slippery shoals for, as Timberlake later wrote, “two or three hours a day, for nineteen days.”

One day, Timberlake’s gun misfired and broke, rendering it apparently useless, and a few hours later, another gun fell overboard and was ruined. In desperation, the men managed to fix the broken gun and killed a bear, whose meat and fur kept the party alive until the group met a Cherokee warrior named Slave Catcher.

Timberlake eventually joined Chief Ostenaco. He visited the Cherokee villages of Tomotley, Chota and Settico, where he observed and took part in peace ceremonies. In his memoirs, Timberlake described the location of Chota and the town-house where he sat for a ceremony. It was “large enough to contain 500 persons, but extremely dark,” he wrote. “Within it has all the appearance of an ancient amphitheatre, the seats being raised one above another, leaving an area in the middle, in the center of which stands the fire, the seats of the head warriors are nearest it.”

The next day, Timberlake’s party set out for Settico, where they were greeted by a group led by a chief named Cheulah, whose body was painted red, except his face, which was half black. Holding a sword in one hand and an eagle’s tail in the other, Cheulah danced for a while, then waved the sword over Timberlake’s head “and stuck it into the ground, about two inches from my left foot.” It was Cheulah’s way of telling Timberlake it was time for peace.

At the various ceremonies, Timberlake did what he thought he should do, including eat the food presented to him and smoke the peace pipes handed to him. But he later wrote that he did not enjoy smoking. “I was almost suffocated with the pipes presented me on every hand, which I dared not to decline,” he said. On one occasion, the smoking made him so sick that he “could not stir for several hours.”

Timberlake remained with the Cherokee for two months, writing detailed descriptions of them, their customs and society and the land on which they lived. Then, reports began to arrive that there was renewed fighting in the north. Timberlake asked Chief Ostenaco to go with him to Virginia to ensure the peace, and the chief agreed, taking two other Cherokee leaders with them.

They traveled overland, going by what is now known as the Great Indian Warpath, and arrived in Williamsburg, Va., in April. It was while in Williamsburg that Ostenaco asked Timberlake if he would take him to London in hopes of meeting the king. Timberlake agreed, and in May the party boarded a ship. They arrived in early June, and the three Cherokee chiefs were an instant attraction, drawing curious crowds from the minute they arrived.

In July the chiefs met with King George III. It was a short audience, and “they were struck by the youth, person, and grandeur of his Majesty,” Timberlake wrote. It was the next year that King George III issued his famous “Proclamation of 1763,” which prohibited settlers from moving west of the Appalachian Mountains.

Upon the party’s return to America, Timberlake was promoted to lieutenant. However, the Virginia General Assembly refused to pay his expenses on the journey to London, concluding that he went not because of orders but because of his own “profit or pleasure.” Embittered, Timberlake sold his parents’ estate to settle his debts.

In 1764, a group of five Cherokees came to Virginia to ask Timberlake to take them to England to tell the king that his proclamation was already being ignored by the settlers. Timberlake at first declined but agreed to do it after a friend offered to finance the trip.

This second journey to England was disastrous. Timberlake’s benefactor died along the way. This time, the king refused to see the Cherokee leaders, and the British government put the chiefs back on a ship for America. Unable to pay their lodging bills, Timberlake was thrown in debtor’s prison. He was writing his memoirs there when he died at the age of 29.

The events described in Timberlake’s memoirs occurred 250 years ago. In recent months their anniversary has been recognized at places such as Fort Loudoun in East Tennessee, Williamsburg and Fort Necessity in Pennsylvania. We now know that Timberlake’s journey did not create a lasting peace, Timberlake did not experience a happy life afterward and both the Cherokee Indians and King George III faced dire consequences when the Proclamation of 1763 was not observed. Nevertheless, Timberlake’s is a remarkable story from which we can learn much about both Cherokee and white culture.

Finally, three fascinating footnotes about Timberlake’s journey:

I asked Barbara Duncan, education coordinator of the Museum of the Cherokee Indian in Cherokee, N.C., whether we have any idea where Timberlake is buried. “We looked into this but concluded that the locations of the burial sites of most of the people who died in the prison have been long since dug up and turned into other buildings,” she said.

In 1969, University of Tennessee researchers used Timberlake’s memoirs to locate the remains of Chota. They found that his map and his description of the Chota town-house were remarkably accurate. Shortly thereafter, however, the site of Chota was buried forever under the waters of Tellico Lake.

Sumter, who accompanied Timberlake on his remarkable journey, also went to debtor’s prison, but a friend loaned him money to get out. Sumter moved back to South Carolina, where he became a Revolutionary War hero (a British general once said he “fought like a gamecock”). After the war, Sumter was elected a U.S. senator, and he lived to be 97 years old. Fort Sumter, the fortification in Charleston where the Civil War began, was named for him. His nickname stuck to his home state, and to this day the gamecock is the mascot of the University of South Carolina.

Many people might wonder if there is a connection between Henry Timberlake and actor Justin Timberlake. Believe it or not, there may be. While he was living with the Cherokee, Henry Timberlake took a Cherokee wife and has Cherokee descendants as a result. In an interview, Justin Timberlake once said his great-grandmother was full-blood Cherokee, which makes it possible that he is a distant descendant of Henry Timberlake.

1 Comment

I believe this to be my relative. I have family history books about him living with the Indians in Virginia and one of four Timberlake history books. The other three printed copies are in Virginia libraries. My mother was Judith Timberlake daughter of David HenryTimberlake. The family resided in Chicago but the family history book is a series of original documents, letters, and journal entries dating back to Virginia during the French Indian War. My relative Henry was born in 1703 in Hanover County Va. he served under George Washington during the French Indian War. He lived with the Cherokees and sued for peace on their behalf after the war. He is in a book “American Scene” published 1974 by the Thomas Gilcrease Museum Association. I have a family copy of that book also. I am headed to my Williamsburg next month and would love to learn more or our history.