Cemeteries tell stories — not only of those who are buried beneath the soil but of the city’s history, its demographics and the challenges the community faced over time.

Elmwood Cemetery in Memphis is a good example, a municipal resting place containing both free people and enslaved, local and international residents and victims of crime, wars and yellow fever epidemics.

“Elmwood has always been open to all people from all walks of life,” said Kimberly Bearden, executive director of Elmwood. “So, it’s been open to the richest and the poorest. It represents the whole history of the city. I think that Elmwood is absolutely a perfect patchwork quilt of our history.”

The cemetery was founded in 1852, its name pulled from a hat and its 80 acres a couple of miles from city limits. Inside its boundaries lie soldiers, politicians, musicians, brothel madams and a few notorious criminals. There’s Robert Church, the South’s first black millionaire; suffragette Lide Smith Meriwether, who founded suffragette chapters throughout Tennessee; Marion Scutter Griffin, Tennessee’s first licensed female attorney; and Civil Rights leaders the Rev. Dr. Benjamin Hooks and Maxine Smith.

The cemetery also became the burial place of hundreds during the yellow fever epidemics of the late 19th century, which decimated the city.

“Memphis was on track to become the biggest city in the South until yellow fever hit it in the 1870s,” Bearden said. “It nearly wiped the city off the map. Half of the city’s citizens fled, so the taxing base left. We lost our charter, and it became known as a taxing district under Nashville.”

Naturally, being the city that gave birth to rock ’n’ roll, Elmwood includes many musicians. Willy Bearden, filmmaker, music historian and Kimberly’s co-author on the book “Elmwood Cemetery, Memphis,” gives music tours to point out the burials of the famous. His tour is one of many offered, covering topics from those who have died in shipwrecks to African American history.

“We also do a huge event called Soul of the City,” Kimberly Bearden said, adding this year it’s Oct. 13–14. “It’s where we have actors who come dressed in costume, and the public meets the people who are buried in the cemetery. We hang bistro lighting in the cemetery, play music and have food trucks.”

In addition to the 80,000 graves, the cemetery is home to 1,400 trees, 13 private mausoleums and unique Victorian cradles that resemble tiny bathtubs. Volunteers have adopted the cradles — up to 200 — for use as specialty gardens that are yet another attribute of the cemetery.

“So many people have told Kim and me that the cradle gardening program kind of saved their lives during the pandemic because it was somewhere to go,” said Willy Bearden. “They were meeting people in a safe place. And so many people made connections during that time, so on the human level, it was very important and continues to be important.”

Elmwood is one of many historic cemeteries in Tennessee. Here are a few others:

Shiloh National Cemetery, Shiloh

It’s a peaceful walk today through Shiloh National Military Park, and it’s hard to imagine that three battles occurred here in 1862 with more than 20,000 dead. Immediately following the Civil War, the U.S. government established the cemetery along the banks of the Tennessee River. Around 4,000 Civil War dead are interred here, with 2,359 of them unidentified. Tall granite gravestones mark those who are named while short stones mark the unknown.

Stones River National Cemetery, Murfreesboro

Another national cemetery within a national park is the Stones River National Cemetery at Stones River National Battlefield near Murfreesboro. More than 6,000 Union soldiers are buried at this Civil War site, with 2,562 unidentified. Other veterans and family members have been allowed to be interred here as well.

Wheat Community, Oak Ridge

Oppenheimer may have built his World War II atomic bomb in New Mexico as part of the Manhattan Project, but the uranium fuel was developed in Oak Ridge. In 1942, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers purchased thousands of acres to build a city where civilians and military would enrich uranium. Part of that property was the Gallaher-Stone Plantation and the Wheat Community, which included an 1850s slave cemetery. The cemetery of 90 or more unmarked graves and a historical marker can be found on the side of the Oak Ridge Turnpike.

Forest Hills Cemetery, Chattanooga

Forest Hills is the final resting place for many of Chattanooga’s politicians but also several Major League Baseball players. Among them is Joseph “Joe” Engel who played for the Washington Senators and later purchased the Chattanooga Lookouts and built the team’s stadium, which now bears his name. Known as the “King of the Minor Leagues,” Engel was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1994.

A baseball great lost in time — no doubt because of her gender — is Virne “Jackie” Mitchell who played professional ball for the Lookouts. Her pitching took down two baseball legends at an exhibition game between the Lookouts and the New York Yankees when she was only 17.

“On April 2, 1931, in an exhibition game witnessed by more than 4,000 Chattanooga fans, Mitchell struck out both (Babe) Ruth and (Lou) Gehrig,” writes Gay Morgan Moore in “Chattanooga’s Forest Hills Cemetery.” “Shortly after the game, baseball commissioner Kenesaw Landis voided her contract, stating that the game of baseball was ‘too strenuous for women.’”

Jonesborough cemeteries, Jonesborough

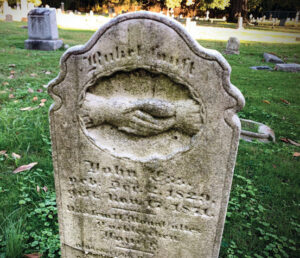

Civil War Confederate Brig. Gen. Alfred Eugene Jackson and early 19th century U.S. Rep. John Blair are among those buried at the Jonesborough City Cemetery. Visitors who want to learn more, including 1800s burial customs, can join tours of the town’s Rocky Hill and College Hill cemeteries by the Heritage Alliance of Northeast Tennessee & Southwest Virginia. Proceeds from ticket sales help fund the ongoing preservation and maintenance of the cemeteries. The Heritage Alliance will offer a tour of the cemetery on Oct. 7 and present a play inside the cemetery titled “A Spot on the Hill” Oct. 13–14 and 20–21. Tickets to both events are available by visiting heritageall.org.

Nashville National Cemetery, Madison

This 64-acre cemetery opened in 1866 to bury Union troops who fell at the Battle of Nashville and other Tennessee skirmishes. U.S. Maj. Gen. George H. Thomas chose the site along the Louisville and Nashville Railroad so that “no one could come to Nashville from the North and not be reminded of the sacrifices that had been made for the preservation of the Union.” A tunnel beneath the railroad tracks connects the cemetery’s two sections, and the main entrance is enhanced by a limestone archway built in 1870. Buildings on the grounds date to the 1800s, and monuments are placed to honor Civil War troops, including the United States Colored Troops.

Mount Olivet, Nashville

Thousands are buried in the state capital’s historic resting place created in 1856, many of whom are community leaders, politicians and country music legends. Some of the lesser-known but interesting graves are those of Confederate spy Fannie Battle, Civil War photographer Carl Giers and astronomer Edward Emerson Barnard who discovered 14 comets and the fifth moon of Jupiter. Country music stars buried at Mount Olivet are Grand Ole Opry’s Del Wood, Rufus Thibodeaux, members of The Stonemans, Bob Moore, Jim Denny and Vern Gosdin, known as “The Voice.”

McGavock Confederate Cemetery, Franklin

After the 1864 Battle of Franklin, about 1,500 Confederate dead were buried adjacent to the 1826 Carnton antebellum mansion that was used a hospital during the conflict. Today, the McGavock Confederate Cemetery is the largest private Confederate cemetery in the country, and both the cemetery and mansion are open to the public for tours.

In the nearby town of Franklin, the Franklin City Cemetery, listed on the National Register of Historic Places, contains four American Revolutionary War veterans.