If you’ve gotten on an elevator at TriStar Summit Medical Center in Hermitage, chances are you’ve been helped on by a tall, friendly man with a warm smile and kind eyes.

That’s Rick Hunt, and he’s known around here as Rick the Elevator Guy. Donning his blue vest, jeans and comfortable running shoes (he walks an estimated 60 miles per month here), Rick is what you might call the strong, silent type.

Rick is strong because he had to be, and he is silent because his tongue and voice box were removed after a squamous cell cancer* diagnosis in 2009. Three rounds of chemo, 35 treatments of radiation and eventual surgeries in 2010 and 2012 left him cancer-free but speechless at age 56. He had smoked a little in the 1970s, but doctors said it was unrelated.

A small bandage just above his collarbone is the only sign that he might have any health problems. Unable to speak or eat conventionally (his meals are blended in a Vitamix with water), Rick the Elevator Guy performs mighty feats of compassion that continue to touch the lives of thousands who pass through those large steel doors on their way to the frustrating world of health care, where clipboard questionnaires await, asking for medical history and medicines they can’t remember the names of.

Rick’s own health crisis began with the detection of an irritating lump on the base of his tongue. His quotes here are taken from an ongoing email conversation I’ve been having with him for the past few weeks.

“At first, I said no thanks to the surgery,” Rick said. “How about juicing carrots? Let’s take the holistic approach? They answered that without the surgery, I’d need hospice care in six to 12 months. They gave us time to think about it.”

“My wife, Elaine, and I headed home from that appointment, and we were both feeling blue. After a few moments, she looked over at me and said, ‘Well I guess you won’t be able to tell me how to drive anymore!’

“We both laughed. We prayed and gave much thought to our next step. They did the surgery, and 12 years later, I’m still here, living one day at a time.”

How I met Rick the Elevator Guy

Getting sick is overwhelming. I know this firsthand. I have been both a patient and a caregiver at TriStar Summit.

I got on Rick’s elevator the first time in August 2018 on my way to a fourth-floor appointment set up by my family doctor. I’m nervous in hospitals, but Rick smiled, and I smiled back. I had been having migraines and “foggy” episodes often associated with early signs of a stroke.

That day changed my life forever. I was diagnosed with a rare blood cancer called polycythemia vera.** The rest of the afternoon was a blur. If I saw Rick at the elevator on my way down, I don’t remember. I’m not even sure how I got home.

Over the next several months, my wife, Deana Lynn, became my caregiver and health coach. She was amazing. She altered my diet, looked up symptoms and treatments online, bought supplements and joined support groups on social media. She went with me to my treatments. Soon I was bouncing back with my usual energy. My migraines stopped, my symptoms subsided and aside from taking a handful of pills every day and seeing far too many doctors on a regular basis (no offense, guys; you know I love ya), I’m doing just fine.

Then, in April of 2021, Deana Lynn started waking up in the middle of the night with lower back pain. I spent every night for the next week dispensing copious amounts of ibuprofen and rubbing her back with jars of Icy Hot — to no avail. The pain just grew worse. After a few doctor visits and a conclusive blood test, she was diagnosed with stage 1 pancreatic cancer.*** It was my turn to take care of her. The next year and a half became a dizzying whirlwind of blood tests, doctor and surgeon consults, countless medications, chemotherapy and radiology.

Deana Lynn’s oncologist, Dr. Brian Hemphill, just so happened to share office space with mine, Dr. Chirag Amin, and we got to encounter the kindness of Rick the Elevator Guy on a weekly basis, if not more often. We would sometimes talk about Rick on our rides home, knowing he must have one heck of a story.

Our sharing of doctors on the fourth floor further reinforced the nickname my wife and I had started to call ourselves: the Cancer Twins.

We had to laugh about this or else fall irretrievably into the abyss. Gallows humor, as they call it, is not for everyone, but it worked for us. Just as Elaine’s driving joke loosened the tension for she and Rick, humor worked as an immediate release valve on this pressure cooker we now called daily life. We laughed as often as we could. In the meantime, we began greeting Rick by name along with the other weary regulars.

After several doctors told us surgery was not an option, Deana Lynn opted out of further treatments. We focused on quality of life. We visited with family. We laughed with friends. We went to the beach. We slow danced, which actually is just hugging to music.

We were eventually forced to let go of everything we had ever hoped to do or be, and Deana Lynn let go of life in our home, surrounded by love, on Sept. 28, 2022. She was 52 years old.

A light in the midst of darkness

As a caregiver, I’ve wandered the halls of too many hospitals, meeting the eyes of fellow wanderers who waited for test results, burdened with all it means to love someone who is sick. Clutching long-cold cups of coffee, we smiled our weary smiles, nodding quietly as we passed each other on our way to our own little nightmares or prayers-come-true.

Rick was there, smiling that kind smile, doing what he could to cut through the malaise he knows firsthand.

During Deana Lynn’s treatments, I would often find a chair in the lobby and watch the elevator doors open and close, a ballet of wounded dancers wandering in and spilling out with their crutches, casts and canes. I’d listen to their cheerful chatter echo through the lobby as they greeted the nice, quiet man in the blue vest.

I’m now alone as I return to Rick’s elevators for fourth-floor follow-ups and bloodwork. Entering the lobby is not easy for me. Going up the elevator is not easy. Sitting alone in the same waiting room where the Cancer Twins held hands, whispered our little jokes and plotted our escape — none of it is easy. I am the surviving twin, and half of me — it feels like more — is gone.

So, I seek out the familiar. I reach for solid and steady touchstones: people who remind me that there is stability in a world that has gone off its axis, rocking wildly as I stumble, trying to stand and move forward.

And I’m sure I speak for many when I say Rick Hunt, the Elevator Guy, has been one of those beacons for me.

The origins of service

“How did you become Rick the Elevator Guy?” I asked.

“I’m not sure of the actual date,” he replied. “But it was sometime before all the COVID stuff started. My wife, Elaine, and I moved to Mount Juliet in 2013. I was trying to enjoy retirement, but something was missing. I was playing golf with neighbors, having a good time, but I wanted to work. I have worked on and off for 50 years. — 33 years with Verizon in Maryland, where I’m from. I finally said, ‘Lord, where would you like me to be as I play this game of life in the fourth quarter?’”

“Sometime later I was at TriStar Summit for a doctor’s appointment, sitting in the lobby. I was watching people get on and off the elevators, and I’d see the doors closing as seniors approached with walkers, and I heard God whisper, ‘Right here, this is where I want you.’”

“I smiled,” Rick continued. “I can’t speak! How can you use me here?”

“After my doctor visit that day,” Rick said, “I went to the hospital administration and said I would like to be a volunteer. I filled out all the paperwork, and soon I was at the elevators, creating my new position.”

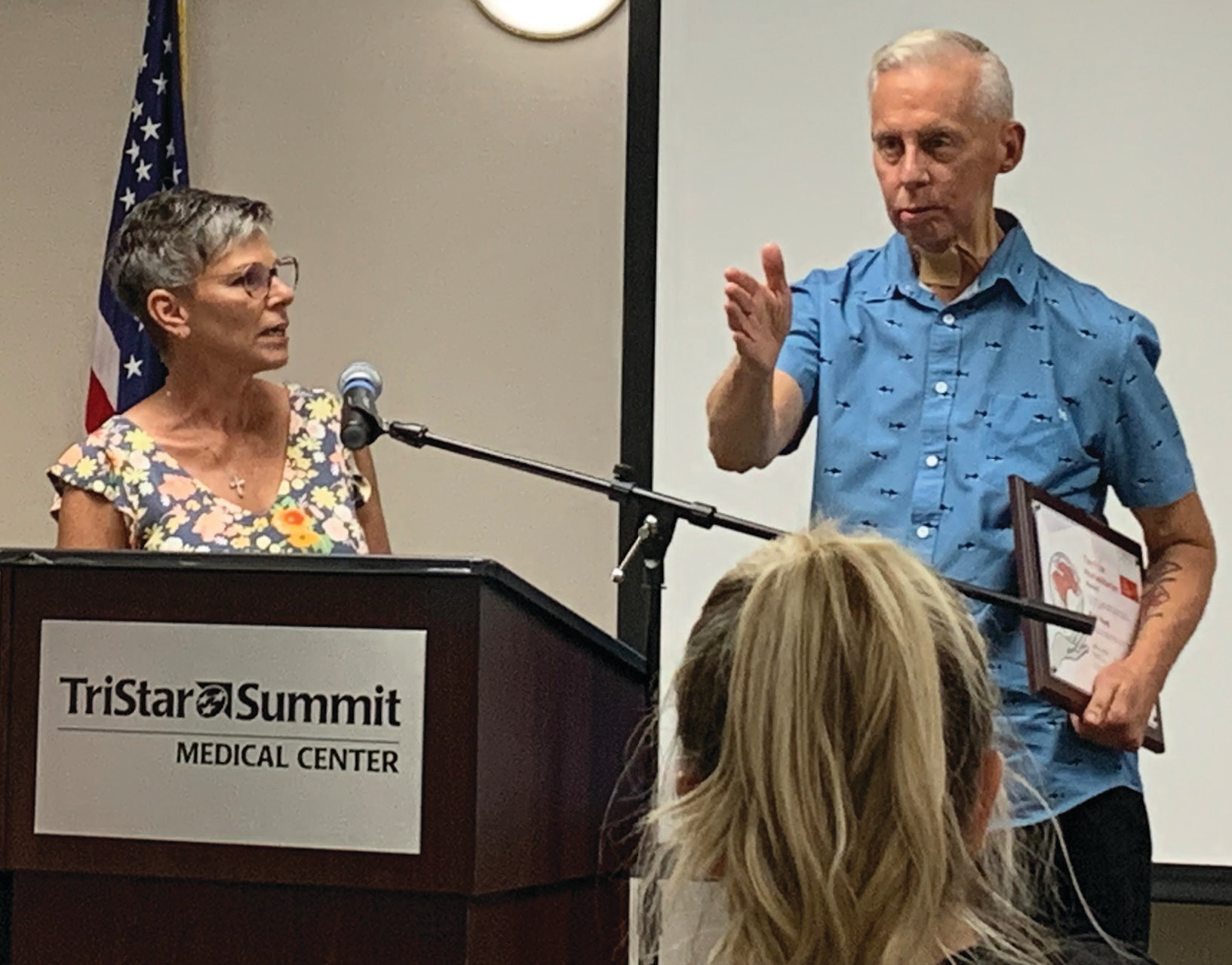

Rick volunteers five days a week — 8–11 a.m., then home for lunch and back at the hospital 1–3 p.m. His role has expanded over the years. He does much more than help folks on and off the elevators. “I walk people back to the ICU or same-day surgery,” he said. “I find extra wheelchairs, I spend time in oncology with cancer patients, and it’s not always just the patients. I try to encourage many on the staff throughout the hospital and doctors’ side who have their own struggles. I help them find a smile.”

We are all part of Rick’s story — and Rick is a part of ours

This was not an easy story for me to write. I’ve been very private about my journey until now. And recalling the painful details of the last few years was not easy. My original intent was to tell Rick’s story and his story alone. I tried a dozen ways to keep me/us out of this, but I realized it had to be included. Deana Lynn’s story and mine are like so many others, and we are what Rick is all about: showing kindness and love to an army of the wounded, diagnosed with bad news and limping as fast as we can to get to an elevator before it closes.

“The world we live in is filled with hate and anger and fear,” said Rick. “When people are at the hospital or doctor’s office, many times they are dealing with serious issues on top of all that other stuff. I don’t care what culture, race, religion or sexuality people have; when they walk in my doors, I want them to feel loved, I want them to know my smile is for them.”

Standing at the gauntlet

Living through a health crisis feels like a cosmic fraternity hazing, and the initiation process is brutal. You limp along an endless gauntlet while one indignity after another is being thrown at you. But as I continue to sit in sad waiting rooms with my fellow wounded, Rick’s words remind me that, despite our differences, we are all the same in every way that truly matters.

And thankfully, there are caring people who help us along the way. We encounter them everywhere: at the coffee counter or the grocery store. And occasionally someone will hold open heavy steel doors, giving us all the time we need to make life’s more difficult steps.

This morning, I went to the fourth floor for a little bloodwork and a consult with my oncologist. And there in the lobby, as I walked in from the cold, I saw the familiar face of my friend Rick with his blue vest and peaceful smile. I said hello, and he said hello back. We chatted for a bit.

I heard him loud and clear. His voice rings deep in my heart. It’s the voice of a warrior, the voice of a friend.

He held the elevator open as I shuffled in with other patients. He pushed the second and third floor buttons — and the fourth for me. He waved as the steel doors softly rumbled closed, and the elevator lifted us upward to whatever awaits.

An elderly woman with a walker said, “What a nice man.”

“I love that guy,” someone else said, “I wonder what his story is.”

“I’ll bet he’s got a good one,” I said with a smile. And I joined my fellow riders in a small, collective sigh.

Detecting cancer

* Squamous cell carcinoma is diagnosed in 1.8 million Americans each year. It is typically not fatal but can spread to other parts of the body and be deadly if not diagnosed and treated. Symptoms of tongue and mouth cancer might include a red or white patch on the tongue that won’t go away, a sore throat that doesn’t go away, a sore spot or lump on the tongue that doesn’t go away, pain when swallowing, numbness in the mouth that won’t go away, painful or burning feeling over the tongue, problems moving your tongue or speaking, a lump in the neck or unexplained bleeding from the tongue not caused by biting your tongue or another injury. In rare cases, one can feel pain in the ear.

** Polycythemia vera is currently diagnosed in about 50 in 100,000 Americans. It causes bone marrow to produce too many red blood cells, raising the risk for heart attack, stroke or blood clots. It is not hereditary and typically occurs in middle age. Symptoms can include migraine headaches, high blood pressure, itchiness of the skin when in the sun or after taking hot showers, shortness of breath, dizziness, flushed face and night sweats. A simple blood test can determine your likelihood of having the disease. If you’re experiencing similar symptoms, ask your doctor for a CBC test, which examines levels of hemoglobin (red blood cell proteins that carry oxygen) and hematocrit (red blood cell percentage in the blood). There is no cure, but the first step for treatment is usually a weekly blood draw to lower the red blood cell numbers. A secondary risk of high platelet count (the sponge-like tissue that forms clots to prevent bleeding) can occur. If that happens, a daily regimen of chemo tablets is often prescribed.

*** Pancreatic cancer accounts for about 3% of all cancers in the U.S. and about 7% of all cancer deaths. The survival rate is about 12% depending on various factors. It is slightly more common in men than in women. It typically doesn’t show signs or symptoms until later stages. Symptoms might include pain in the stomach, side or lower back; trouble with food digestion; weight loss; bloating of the stomach; and yellowing of the eyes and skin. If you are experiencing these symptoms, ask your doctor for a tumor marker test such as a CA19-9, and get scanned. The most often used imaging tests for detecting pancreatic cancer are ultrasound, CT, MRI or PET scans.