The Tennessee Valley Authority built a dam in Johnson County in the 1940s, permanently flooding the valley that included the small town of Butler and creating Watauga Lake. There is nothing unique about this. TVA and the Army Corps of Engineers built dams and flooded valleys all over Tennessee and north Alabama between the 1930s and 1960s.

What is unusual about Butler is that, in the years following their move to higher ground, some of its former residents chose not to throw away some of the old possessions, furniture and photographs that reminded them of life in their hometown. They eventually put all of this memorabilia in a single place, now known as the Butler Museum. Because of this, Butler of the early 1900s may be the best-preserved and -documented small town in Tennessee.

I recently reflected on this irony on a visit to the Butler Museum. You can learn a lot there about what communities such as Butler were like, why TVA flooded such places and what the residents went through.

It is important to remember, for instance, that there was — and is — more to TVA than electricity. One of its main purposes was flood control. Butler, along with other locations along the Watauga River, flooded in 1867, 1886, 1901, 1902, 1916, 1924 and 1940. Not only did these floods destroy hundreds of homes and businesses in Butler, it did the same in every community downstream (Elizabethton, for instance). The 1940 flood destroyed the railroad line from Elizabethton to Mountain City, and it was never rebuilt.

Herman Tester, a native of old Butler and the chairman of the Butler Museum board of directors, told me on my recent trip to the museum that he was still learning about things that were destroyed by the Watauga River’s many floods.

“Look at this panoramic photograph of the Luppert Lumber Company, which was right here in Butler,” he said, referring to a detailed photo on the wall. “Look at all this equipment and all these buildings and all these homes.

“This is the type of business that obviously struggled to stay here because of the floods. And I grew up here and had never even heard of this company!”

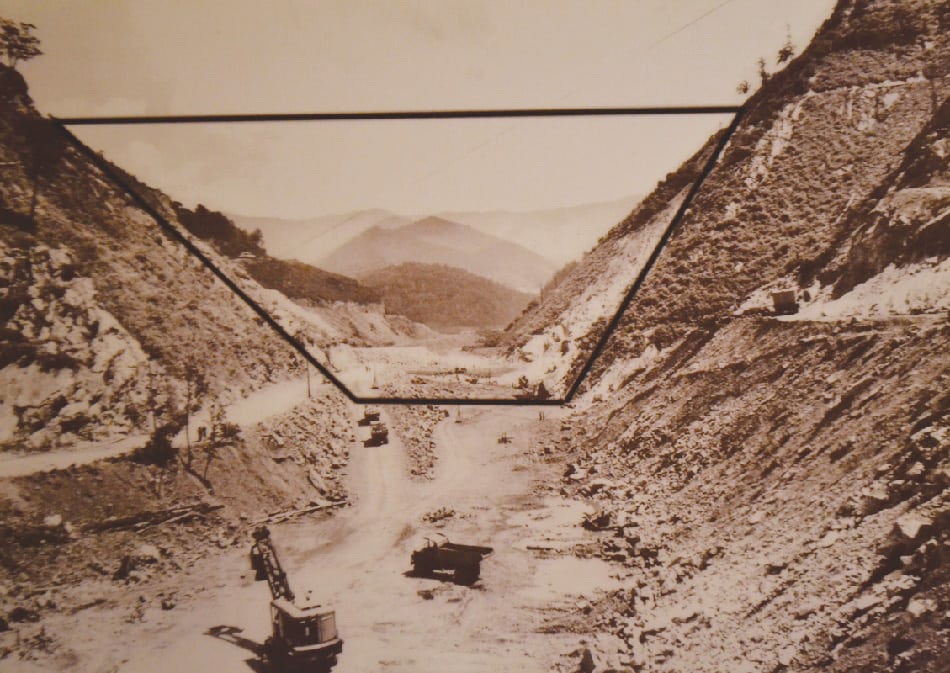

TVA first started building a dam on the Watauga River in 1942 but left the project half-finished during World War II. By the time it resumed work on the dam in 1946, many residents of Butler doubted that TVA would ever finish. But when the authority began buying up homes, farms and businesses, it was obvious that everyone had to move.

Many residents decided to move together and organize a new planned community on a subdivided farm. They originally called this community Carderview. Five years later, they decided to change the name to Butler to honor the name of their original town.

In the early 1900s, Butler was a typical East Tennessee tobacco-farming and lumber town with about 750 residents. It had a post office, grocery stores, furniture store, drug store, doctor’s office, gas stations, several churches and about a hundred houses. Butler’s most notable institution was Watauga Academy, which traced its origins to a school started in 1871.

At the museum, you can see many of the things that were moved when the water started to rise. There is equipment that was used in the Butler post office, a horse-drawn hearse and several coffins, furniture from homes, equipment from Whiting’s lumber mill and even the chair from Kyle Stout’s barber shop.

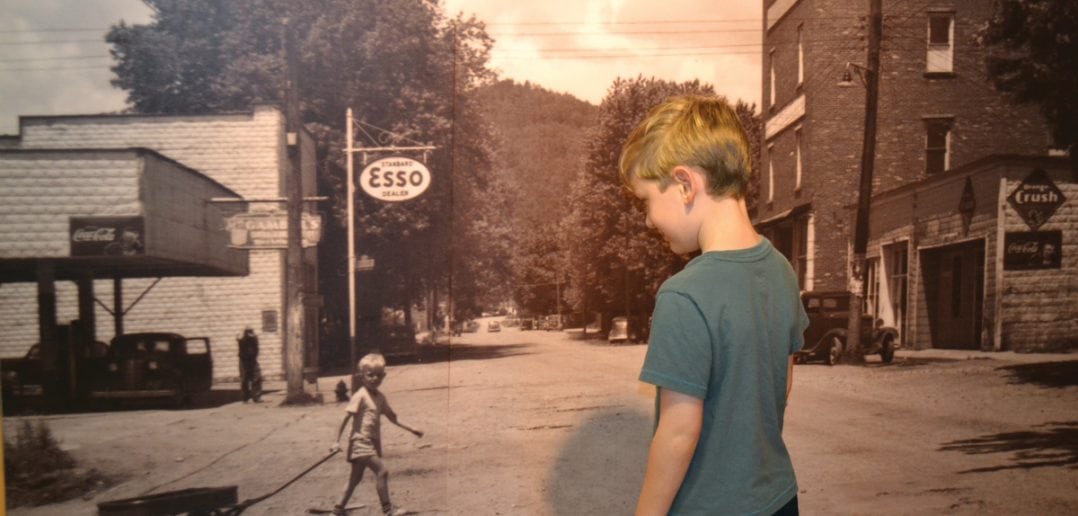

I would argue that photographs are the most interesting part of this museum. There are photos of old houses, children growing up in Butler, dam construction and people from Butler who served in the U.S. military, including a longtime member of the U.S. House of Representatives named B. Carroll Reece. There are wonderful photos of church get-togethers. There are photos of structures being moved to higher ground.

The remains of more than 20,000 people had to be moved to make way for TVA lakes. But over the years, I have found few photos that document the process of cemetery relocation, likely a reflection of the TVA propaganda machine. However, there are at least three photos at the Butler Museum that show people digging up old graves. They speak volumes about the grim, personal impact that such forced relocations had on long-term residents.

In 1983, TVA drained Watauga Lake to work on the dam. For a few weeks, the remains of old Butler were exposed again, and aged residents flocked back to inspect the remains of the town. They found roads, stone walls, foundations and even the solid rock walls of an old shoe shop in the middle of town. This unusual event is well documented at the museum, and you can even see television news broadcasts about what was for many former residents of Butler an emotional homecoming.

The Butler Museum is a wonderful place that, like so many other small local museums in Tennessee, operates on volunteer time and donations. The institution is adding to its holdings and not long ago moved to the museum grounds a general store building that had been in old Butler.

I highly recommend visiting the museum and suggest that you go to www.thebutlermuseum.com for more information like operating hours and more.