In 1913, President Woodrow Wilson imposed Jim Crow laws on federal government employees, causing the highest ranking Black federal employee to resign in protest.

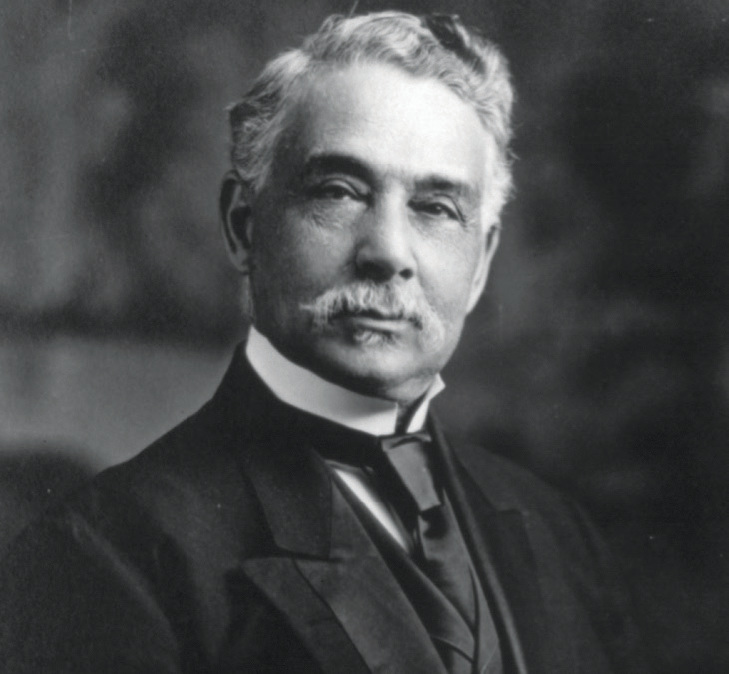

That man, James C. Napier, happened to be from Nashville.

Napier was born in 1845 — the day after Andrew Jackson died, it turned out. His parents, William Carroll and James Elizabeth Napier, were enslaved at that time, but the family was granted its freedom in 1848.

James was sent to a school for free Black children until 1856, when such schools were outlawed by the Nashville city council. “Classes were begun for the young negroes in a small house which stood on North Vine Street,” the Tennessean newspaper explained many years later. “Then one morning a white man appeared at the door, came in rudely without knocking and told the teacher to send the children home and to leave the city in 24 hours.”

Napier was then sent to Ohio where he attended Wilberforce College and then Oberlin College. He later went to Howard University in Washington, D.C., where he got a law degree.

In 1872, the 27-year-old James Napier returned to Nashville. Since it was hard for a Black lawyer to find work at first, he worked for the Internal Revenue Service for several years. However, he eventually rose to be a leader in the city’s African American community and was part of every political struggle fought by Nashville’s Black residents in the Reconstruction era. Councilman Napier led the battle to get Nashville’s government to hire African American teachers, and citizen Napier helped organize Nashville’s fire engine company.

At a time when the vast majority of Black citizens were Republican, Napier was a member of the state’s Republican Executive Committee. In 1904, he co-founded a financial institution called the One Cent Savings Bank (now the Citizens Bank and Trust Company).

National prominence knocked at his door once.

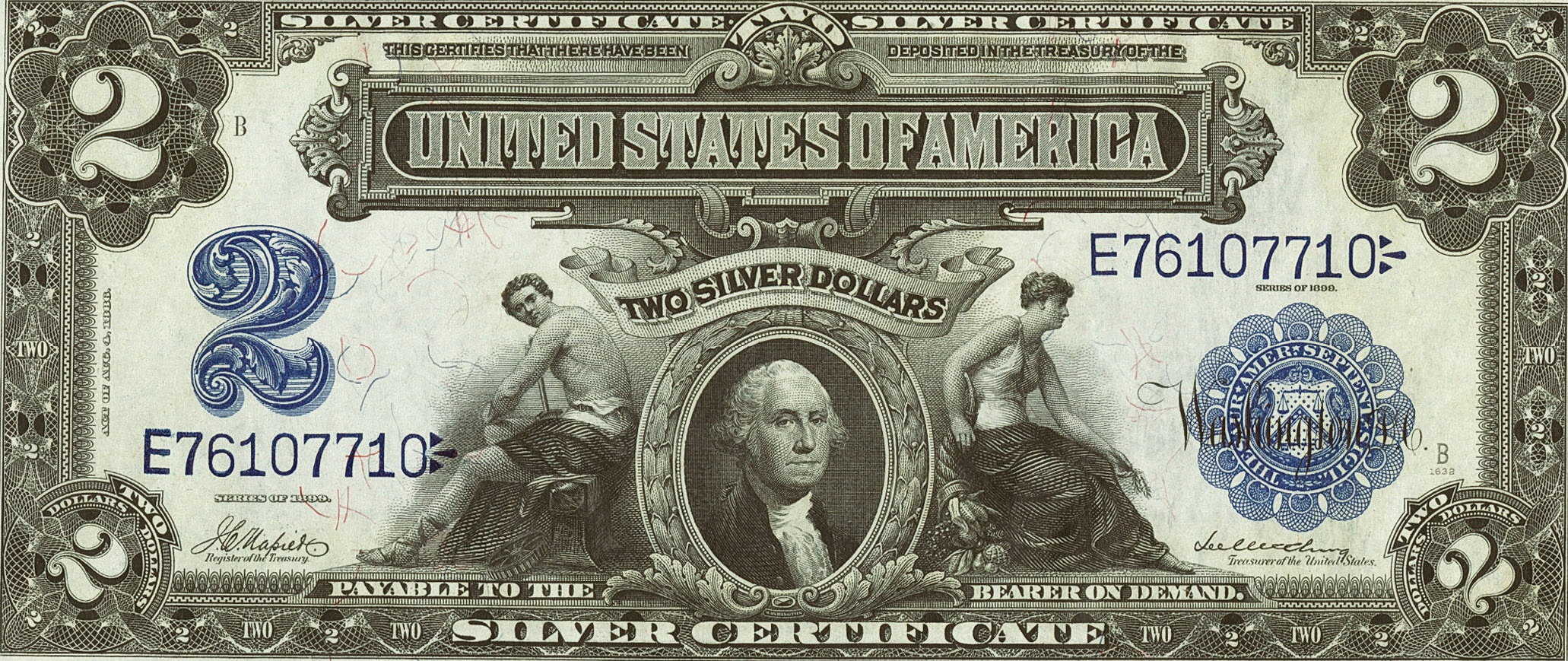

During the Civil War, a position was created in the U.S. government called register of the Treasury. According to Wikipedia, its duties included “filing the accounting records of the government, transferring and cancelling federal debt securities, and filing the certificates of U.S.-registered ships.” The signature of the register of the Treasury appeared on almost all U.S. currency until about 1923.

In any case, remember that during the half century after the Civil War, Republicans were consistently elected president. Also remember that in the half century after the Civil War, most Black Americans voted Republican.

Starting in 1897, the president of the United States began appointing Black men to be register of the Treasury. The first African American to hold this position was Blanche Bruce of Mississippi; then Judson Lyons of Georgia; then William Vernon of Kansas.

In March 1911, President William Howard Taft appointed James Napier to register of the Treasury. “The new register (Napier) is a man of striking appearance and most graceful manners,” the Memphis News-Scimitar reported. “He is a lawyer and a banker and has achieved success by the modest dignity of his bearing and the superiority of his intellectual attainments.”

The next year, however, there was a major shift in executive branch power. In November 1912, Democrat Woodrow Wilson was elected president — the first Southerner to ascend to that position since before the Civil War. After he took office, Wilson took steps to segregate the federal government. “In the Treasury Department, signs have been placed over the doors of the toilets which read ‘White men’ and ‘Colored men,’ ‘White women’ and ‘Colored women,’” the New York Age reported.

As a result of Wilson’s orders, James Napier resigned his post as register of the Treasury — a position that would no longer go to a Black man.

Napier returned to Nashville and returned to his position as a civic leader and lawyer. In 1937, a 37-year-old Tennessean reporter named Helen Dahnke interviewed him at his office. “Behind James Carroll Napier, Nashville’s first negro citizen, lies ninety-two years of eventful living,” she wrote. “As a banker and the oldest member of the Nashville bar he seems remote from the days of slavery, lack of opportunity and prejudice when he was born. Yet he has managed to bridge the two eras of his people without bitterness and to maintain a pride and dignity which any individual might do well to copy.”

Dahnke told Napier her newspaper had proposed that a public housing project then under development be named for him. That did occur, and the place still exists (Napier Homes). There is also an elementary school and a public park named for Napier.

James Napier died in April 1940. For the rest of the 20th century, there were many articles written about the man and his legacy in various Nashville and Tennessee publications. However, these articles almost never mentioned the circumstances under which he resigned his national post. That anecdote was relegated to obscurity until the recent digitization of newspaper records, which has brought to light the stories written in the North when Napier resigned.