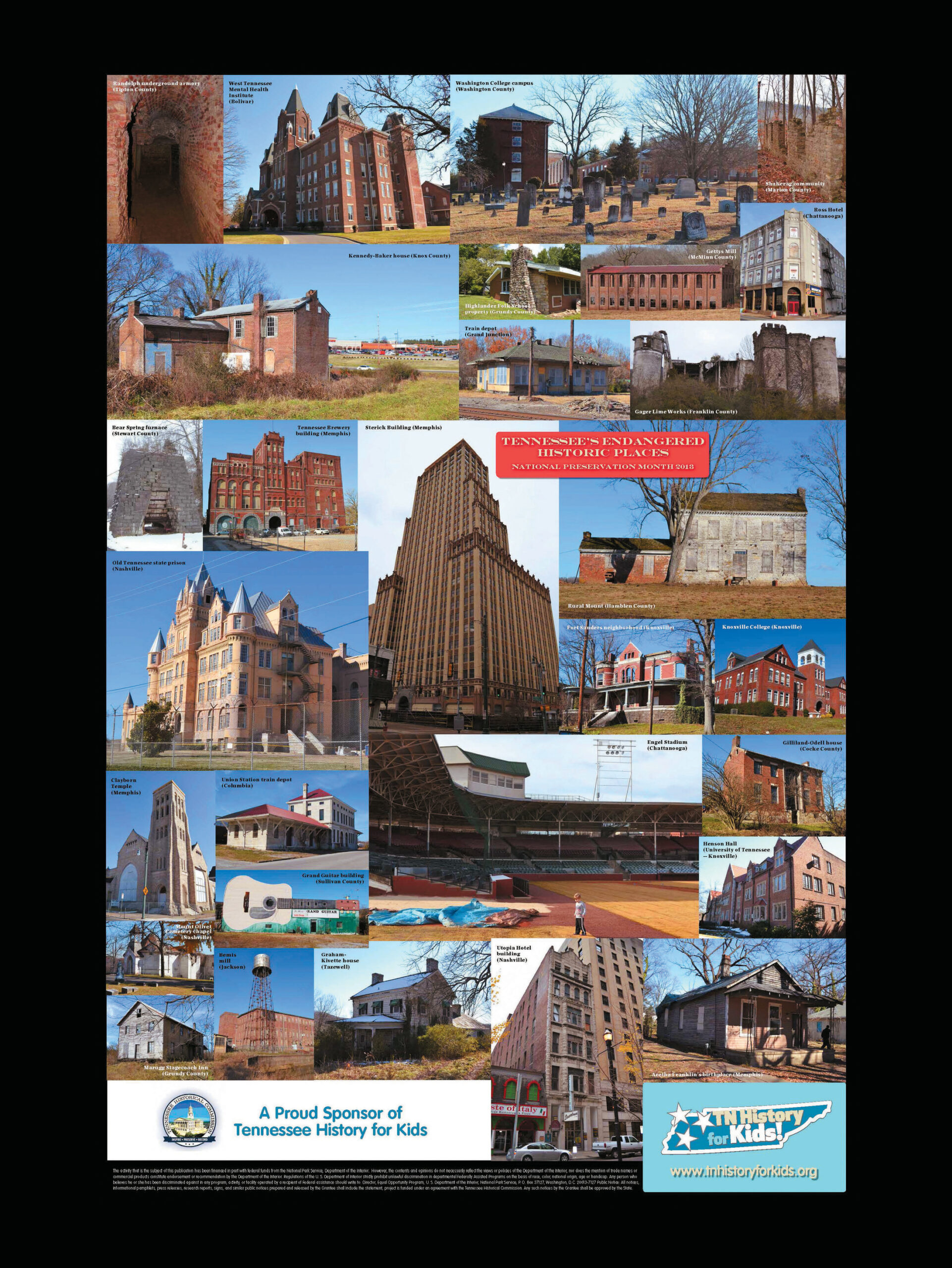

Eleven years ago, Tennessee History for Kids and the Tennessee Historical Commission produced 10,000 copies of a poster called “Tennessee’s Endangered Historic Places.” It featured photographs of 29 old structures (mostly buildings) that were in danger of being torn down or falling down. We gave the posters to teachers to hang in their classrooms, and they were snatched up in a matter of weeks.

This article will update what has happened to many of these old buildings. Some have been renovated, some are being worked on as we speak, some have been torn down and some are still sitting in much the same state that they were in 2013.

Starting in East Tennessee and moving west, here are buildings from the poster that can be placed in the “saved” category:

There’s an old house across from the Cedar Bluff Home Depot in Knoxville. For lack of a better name, it is known as the Kennedy-Baker-Walker-Sherrill House and was built in the 1840s. Since the poster came out, a Knoxville developer bought and restored the house, and a business called Knox Wellness is now operating there.

The night before he died, three-time Democratic presidential nominee William Jennings Bryan slept in downtown Chattanooga’s Ross Hotel. The hotel was built in 1888, remained open until about 1979 and was mostly or completely empty for several decades after that. I’m happy to report that the four-story, 40,000-square-foot structure has been renovated and is used as a combination of restaurants and apartments called the Tomorrow Building.

For many years, I walked past the skinny, six-story, empty Utopia Hotel building in downtown Nashville and wondered what would become of it. Today, the structure (built in 1891) is part of the Dream Hotel in downtown Nashville, which consists of not only the Utopia Hotel building but also the Climax Saloon building next door. The Dream Hotel is one of Nashville’s “downtown boutique” hotels. (If you have to ask how much a room costs, you probably can’t afford one.)

Columbia’s Union Station Depot (built in 1902) has been renovated by David Hill, president of a Maury County company called WireMasters. “I grew up in Maury County and hate to see so many old historic properties disappear,” he explains. “The architecture and craftsmanship on display in the train depot are skills that are no longer used or even remembered.” The depot is private property, with the public invited to the occasional open house. If you want to see some beautiful photos of its interior, go to hillhistoricproperties.com.

In West Tennessee, when locals learned the Grand Junction Train Depot was scheduled to be razed, concerned citizens formed a nonprofit entity dedicated to saving the structure called the Grand Junction Depot Museum Corp. (GJDMC). The group purchased the depot from the railroad and has spent an estimated $50,000 to restore its exterior. “There were trees growing inside the building when we started,” says Kathy Ledbetter, chair of GJDMC. “But now it looks great and is structurally sound.” The group intends to turn the depot into a museum and public space. “We have a lot ahead of us — fundraising, installing modern plumbing, bathrooms, electrical work, woodwork,” she says. “We’ll get it done.”

The Tennessee Brewery Building in downtown Memphis was built in 1890 and sat vacant after 1981. In 2014, Memphis business leader (and cellphone tower builder) Billy Orgel paid $825,000 for it. The next year he began converting it to residential use, and it has been an urban residential success story since. For photos of it, go to atthebrewery.com.

Now for some currently being renovated:

Washington College in Washington County has not been a degree-awarding institution for about a quarter-century, but many of the buildings on its campus are still standing. These structures are cared for by a nonprofit called Washington College Academy, and the former campus is now used for art classes, festivals, bluegrass jam sessions and early voting. “We focus our resources to keep up and restore Harris Hall (built in 1842), Temple Carnegie Hall (built in 1909) and President’s House (built in 1842),” says spokesperson Debra Lewis. The organization had a setback a couple of years ago when a windstorm took out the roof of the campus gym, requiring a $50,000 repair. But the bottom line is that the once-abandoned campus is being used, and there are capable people on the board of Washington College Academy looking out for it.

Thanks to a $750,000 grant from the state, Claiborne Heritage Center announced last year that it was restoring the Graham-Kivett House to be its future home. “We secured funds and have put up a new roof and repaired the stonework, so now the building is absolutely solid and waterproof,” says Karen Clark of the heritage center. The plans for the 1810 building include a wing, yet to be financed. “This is a matter of when we complete the project — not if.”

Memphis’ Clayborn Temple featured heavily in the Civil Rights Movement and the sanitation strike of 1968. Built in 1892, it sat empty for decades but is now about halfway through a complete restoration that will, by its end, cost about $25 million. “We’ve already restored the exterior of the building, which includes the roof, stonework and replacing stained glass windows that had been destroyed,” says Brooke Sarden, managing director of Historic Clayborn Temple. “Recently we had the original organ removed from the building to be completely restored and then put back in.” The African American Cultural Heritage Action Fund, a national entity, is financing most of the renovation. When completed, Clayborn Temple will be open to the public and used for live performances and speeches.

Two large and important things whose fates are yet to be sealed:

Engel Stadium is a beautiful place for baseball and even has covered bleachers in its infield. But it hasn’t had a tenant since the Chattanooga Lookouts moved to AT&T Field 25 years ago.

The good news is that the stadium is now the property of the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga. The less-than-good news is that UTC hasn’t decided what it can, and can’t, afford to do with it, says university spokesman Chuck Wassertrom. “The recent campus master plan contemplates a historically appropriate use of the site,” he says, “but that’s all I can say right now.”

When it opened in 1930, Memphis’ Sterick Building was the tallest building in the South, at 29 stories and 365 feet high. It’s been empty since 1986.

However, the Sterick Building has a champion in its corner, that being developer Stuart Harris. Tennessee has never seen an old building of the Sterick’s size and magnitude renovated to date — but don’t tell Harris that. Harris’ business (Constellation Properties) owns the building and has publicized plans to renovate it — much like it did the eight-story, century-old Commonwealth Building in downtown Memphis a few years ago.

Like the Commonwealth Building, Harris hopes to bring back the Sterick Building with a myriad of uses. “We’re looking at a combination of residential, hospitality and offices — like coworking space,” he says. “The residential component would need to be rented, at least at first, because the building is on the national register, and we would be using federal historic tax credits.”

When you are renovating a 340,000-square-foot building, you have to raise a lot money through different sources. Harris says that if all goes well, the renovation will begin in 2025, and people might move back in two years after that. Stay tuned!

Finally, here are some of the structures on the poster that have been torn down:

The Grand Guitar building on Interstate 81 in Bristol (which was shaped like an acoustic guitar) was torn down by its owner in 2019.

Pickle Mansion in Knoxville’s Fort Sanders neighborhood was torn down around 2015. Like other former houses in that once-proud area, its lot is now used for parking and will probably one day become student apartments.

In recent weeks, Henson Hall at the University of Tennessee was razed to make way for an expansion to the Haslam College of Business.

The chapel building at Nashville’s Mount Olivet Cemetery burned down in January 2015.

Last but not least, the main Bemis Bag Factory building in Madison County was torn down in 2017, an event that broke the collective hearts of everyone in the Bemis Historical Society. The society’s longtime chairman, Joel Jackson, says there was no alternative. “Three different companies came out and gave a price on stabilizing it and fixing the roof, and those bids came it at $600,000 or $700,000,” he says. “At the same time, the company was offered a large amount of money by a salvage company for the estimated 5 million bricks in its walls.”

The Bemis factory building site has been converted to a public park. Meanwhile, the Bemis Auditorium — a historic building in its own right — is now property of the Bemis Historical Society. It also contains a small museum, but it is open by appointment only (see bemishistory.org for more information).