Drayton Callison seeks out America’s unusual and abandoned sites for his “Dray’s World” videos on his popular YouTube channel. On a trip to Tennessee, he stumbled upon something unexpected in the small town of Sparta. There in the Mt. Gilead United Methodist Church cemetery was a collection of “tent graves,” burials topped with concrete stones in the shape of a tent.

“It was unique,” Callison said. “I wondered if there were other places in the world that had that. I would have liked to have known who they were and why they did those.”

Callison is not alone. Reasons for the tent graves popular in the 19th and 20th century differ. Some think the graves like those found in White County were meant to withstand weather and animal intrusion while others believe they were created for their aesthetic value. Although relatively rare, others can be found in parts of Kentucky and northern Alabama.

These unique tent graves are just some of the fascinating aspects of Tennessee cemeteries.

Celebrities

Naturally, many of Nashville’s famous country singers are buried in several city cemeteries. Woodlawn Memorial Park, for instance, includes the final resting places of Porter Wagoner, George Jones, Eddy Arnold, Tammy Wynette and Lynn Anderson. A unique feature of Woodlawn is the Lynn Anderson Rose Garden with its Lynn Anderson hybrid rose bushes named by the National Rose Society of America. The garden stands in honor of Anderson’s hit song, “Rose Garden.”

A few miles northeast of Nashville lies Hendersonville Memory Gardens, chosen by many country music stars, the most notable Johnny Cash, June Carter Cash, “Mother” Maybelle Carter and Anita Carter.

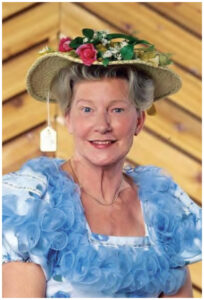

In Williamson County, fans can visit Mount Hope Cemetery Franklin to honor celebrities such as Sarah Ophelia Colley Cannon, well-known under her stage name, Minnie Pearl. With her trademark sales tag hanging from her hat, Cannon was a regular at the Grand Ole Opry.

Mount Hope also is home to four U.S. congressmen and music producer Felton Jarvis who produced Elvis Presley from 1966 to 1977.

Visitors to the Alex Haley House and Museum State Historic Site learn about the Pulitzer Prize-winning author of the best-selling novel “Roots” but also visit his grave and those of his grandparents, Queen and Alex Haley. From 1921 to 1929 and during some subsequent summers, Haley lived at the Henning home with his grandparents and listened to oral accounts of his family history that inspired his award-winning novel.

Established in 1872, Greenwood Cemetery in Clarksville pays homage to many fallen Confederate soldiers with its dramatic monument, but it might be actor Frank Sutton’s grave people visit most often. Sutton played the energetic Sgt. Carter on the TV sitcom “Gomer Pyle, U.S.M.C.”

Tennessee pioneers

Dating back to the state’s settlement and founding is Clarksville’s Riverview Cemetery, created in 1800 by Revolutionary War hero Valentine Sevier, brother of Tennessee’s first governor, John Sevier. Valentine Sevier lies on this property that overlooks the Cumberland River as do Revolutionary War soldier Robert Nelson, U.S. congressman James B. Reynolds and other early Clarksville pioneers, settlers, civic leaders and statesmen.

Clarksville’s Greenwood contains the graves of two Tennessee governors, Willie Blount and Austin Peay, the latter who also founded Austin Peay State University.

Explorers, champions and whiskey lovers

Famous explorer Meriwether Lewis was a leader of the Lewis and Clark Expedition that mapped out the Louisiana Purchase from 1804 to 1806. On Oct. 11, 1809, the man who helped shape the expansion of the United States was found dead in Hickman County at age 35 from two gunshot wounds. It’s unclear if Lewis was murdered or took his own life, but most claim he died by suicide due to financial troubles.

Lewis is buried beneath the Meriwether Lewis Monument in Hohenwald at Milepost 385.9 on the Natchez Trace Parkway, a circular column with a broken top that signifies a life cut short.

McNairy County Sheriff Buford Hayse Pusser took on the “Dixie Mafia” and a variety of vices running rampant near the Mississippi state line. The life story of the former Marine became the 1973 semibiographical film “Walking Tall.” Pusser died in a suspicious car accident in 1974 and is buried in the Adamsville Cemetery.

Adamsville is also the birthplace of “Daddy-O” Dewey Phillips, one of rock ’n’ roll’s pioneering disk jockeys, who is buried in nearby Crump Cemetery.

Jasper “Jack” Newton Daniel, who learned the art of making charcoal-mellowed Tennessee whiskey from an enslaved man named Nathan “Nearest” Green, went on to create Jack Daniel’s in Lynchburg, one of the world’s top whiskey distilleries.

Daniel left his finances, including the business’s thick iron safe, in the hands of his nephew Lem Motlow. Early one morning when Daniel was about to travel and in need of the safe’s contents, he attempted to open it on his own. He didn’t know the combination and kicked the safe in frustration, shattering his big toe in the process.

“He doesn’t see a doctor about it, thinks he can walk it off,” said Jack Daniel’s tour guide Ben Spears. “All those bad decisions lead to an infection, and then the toe’s amputation, since that’s all they can do at that point in history.”

The infection spread, and Daniel died. He was laid to rest in the nearby Lynchburg Cemetery, not far from his famous distillery. His grave contains two cast-iron chairs in case visitors wish to pay respects for his spirited life.

On the other hand, Nearest Green’s headstone at Lynchburg’s Highview Cemetery reads, “Father, husband, mentor, the greatest whiskey maker the world never knew.”

African American cemeteries

Tucked behind the Ephesus Seventh-day Adventist Church on Cumberland Drive in Clarksville is one of the oldest cemeteries dedicated to Tennessee’s African American citizens. Mount Olive Cemetery dates to 1817 and contains gravesites of at least 1,350 African Americans, including more than 20 members of the U.S. Colored Troops. The Mount Olive Cemetery Historical Preservation Society was established in 2004 to protect the 7.24-acre property — 90% of the graves are unmarked — and, in 2020, the cemetery was added to the National Register of Historic Places.

In 1863, the former enslaved Stephen Cole purchased land in Montgomery County that would become the oldest tract of land continuously owned by African Americans in the county. Golden Hill Cemetery is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Many gravestones in both Golden Hill and bordering Evergreen Cemetery, also an African American burial site, were designed by Hiram Johnson, an African American stonemason and sculptor who worked for Samuel Hodgson, owner of Clarksville Marble Works.

Joshua Beck, a Union supporter living in northern Chattanooga, donated a 1-acre site around 1865 for the burials of African American contraband soldiers and members of the city’s African American community. Beck Knob Cemetery contains 188 known burials, but only 42 graves contain markers. It’s believed that many graves have not been discovered.

William Gaines started a church and school for African Americans in the hamlet of Comfort in Marion County, not far from Chattanooga. The Gaines Chapel was in operation from 1881 to 1922, but all that is left of the chapel, school and the Comfort community is the Gaines Chapel Cemetery across the street from the Battle Creek Baptist Church.