It is the strangest item in the Tennessee Historical Society’s collection. The Tennessee Museum puts it on display once a year. When the museum does so, there is often an article about it in one of the Nashville newspapers, along with a photo of it and the little case in which it is stored.

It is a human thumb.

And it is not just any thumb, mind you. The thumb put on display used to belong to none other than John Murrell.

Who was John Murrell? Was he an ill-fated hitchhiker?

Not exactly. John Murrell was an outlaw who operated in the 1820s and 1830s on the Natchez Trace as well as points as far west as Arkansas. It is safe to say that few living Americans have heard of John Murrell. But that has not always been the case.

Not exactly. John Murrell was an outlaw who operated in the 1820s and 1830s on the Natchez Trace as well as points as far west as Arkansas. It is safe to say that few living Americans have heard of John Murrell. But that has not always been the case.

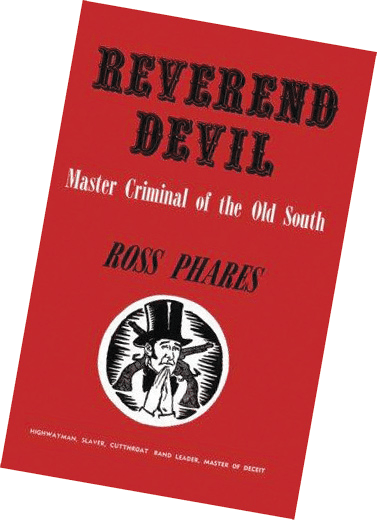

There have been many books about Murrell. The first was written in the 1830s by Virgil Stewart, who claimed to have spied on Murrell and learned firsthand about Murrell’s murders, robberies and his secret crime organization, the “Mystic Clan.” Over the years, there have been about a half-dozen more books. They generally repeat much of the information in Stewart’s book, painting a picture of Murrell as a clever, cutthroat, ruthless criminal — a “land pirate,” so to speak.

According to most of these books, Murrell routinely latched onto fellow travelers along the Natchez Trace, often in the guise of a friendly and articulate traveling preacher. Then he might cut their throats and steal their money, or, when he preferred, he would preach publicly and have accomplices wander through the crowd, picking pockets and stealing horses. Murrell routinely “helped” slaves escape from bondage only to trick them and sell them to another slave owner or slave trader, the stories say. Many books also claim that Murrell planned to incite and profit from a mass slave rebellion to take place on Christmas Day 1835. However, that plan was thwarted when Murrell was arrested and convicted for stealing slaves.

Mark Twain talks about John Murrell in his book “Life on the Mississippi.” In “Tom Sawyer,” Tom, Huck and Injun Joe are all searching for Murrell’s lost treasure, said to be hidden in a cave near the Mississippi River.

In 1940, Humphrey Bogart played John Murrell in a movie called “Virginia City.” A fictionalized John Murrell appeared in 1950s TV shows such as “The Adventures of Jim Bowie” and “Riverboat.” Murrell was the central figure in the 1960 movie “Natchez Trace” (posters for which hang at the Zaxby’s restaurant near my house).

All of this might make you wonder how it is that our knowledge of John Murrell has diminished over the years. I have two theories for this. One is that our awareness of just about everything Tennessee-historic has dimmed over the years. But the other reason is that the stories about John Murrell were almost certainly exaggerated during the 120 years after his death.

As best I can tell, John Murrell was twice convicted of crimes. The first time was in the 1820s in Nashville when he was branded, whipped and sent to jail for horse theft. The second time was in 1834 in Jackson when he was convicted of stealing slaves.

Murrell was pardoned in 1844 and moved to Pikeville in Bledsoe County. He died only a few months later. In a deathbed confession, Murrell admitted to many of the crimes he had been charged with. But he said he had never killed anyone.

Assuming Murrell was telling the truth — or even if he wasn’t telling the complete truth — why did this criminal from Tennessee become so famous? The story may have something to do with the nature of the times.

In the early 1830s, because of the Nat Turner rebellion in Virginia, white Southerners were nervous about the idea of a slave uprising. Virgil Stewart’s 1835 written claim that John Murrell and his gang of outlaws were masterminding a slave rebellion was taken seriously at the time. In fact, after the release of Stewart’s booklet, many slaves throughout the South were questioned and lynched for their alleged roles in the conspiracy, especially in Mississippi.

But if there was no planned slave rebellion, why would Stewart have claimed there was? Perhaps he was lying about the whole thing, trying to make himself out to be a hero in the antebellum South.

In any case, the “Murrell Excitement,” as it was known at the time, was the Southern equivalent of the Salem witch trials. Innocent slaves were the victims.

Finally, one more point about the era of John Murrell and his alleged “slave rebellion”: The 1830s was the decade in which books about David Crockett were best-sellers. All of these books combined truth with fiction, actual occurrences with ridiculous exaggerations. Even Crockett’s own autobiography is filled with tall tales about falling into huge holes and hand-to-hand fighting with black bears. So it is very possible that a story about a simple outlaw could get blown out of proportion.

All of this brings us to the thumb:

Sometime after Murrell was buried in 1844, grave robbers allegedly dug up his body at the Smyrna Cemetery near Pikeville. The outlaw’s body somehow ended up at a Nashville medical school six decades later. A physician severed one of Murrell’s thumbs and donated it to the Tennessee Historical Society in 1895.

This story may be just as preposterous as the one about Murrell’s Mystic Clan and his planned slave rebellion. It is certainly true that 19th-century grave robbers would dig up corpses and sell them to medical students as cadavers. But why would grave robbers unearth a corpse in Pikeville, then transport it all the way across the state?

The more likely scenario is that medical students at the University of Nashville gave names to all of their cadavers (as medical students probably still do). Since they all knew the legend about Murrell, they gave that name to one, and it stuck. Eventually, someone sliced off his thumb and donated it to the Tennessee Historical Society as a bit of a joke.

“How this mummy came into the Medical Department of the University of Nashville, and where it rested from 1838 to 1851 or whether the whole thing is a fanciful romance, a hoax out of whole cloth, I am trying to determine,” Dr. S.S. Crockett of the Tennessee Historical Society wrote in 1917. “The more I look into the matter, the more I believe that the tradition was probably without any foundations whatever.”

The more I read about John Murrell, his Mystic Clan and his thumb, the more I come to the same conclusion about many of these stories. But I’m sure that won’t stop people from making movies and writing ghost stories. And it won’t stop people from being interested in the mysterious thumb and the cute coffin put on display every year at the Tennessee State Museum.