Wayne Brezinka transforms trash into artistic treasure

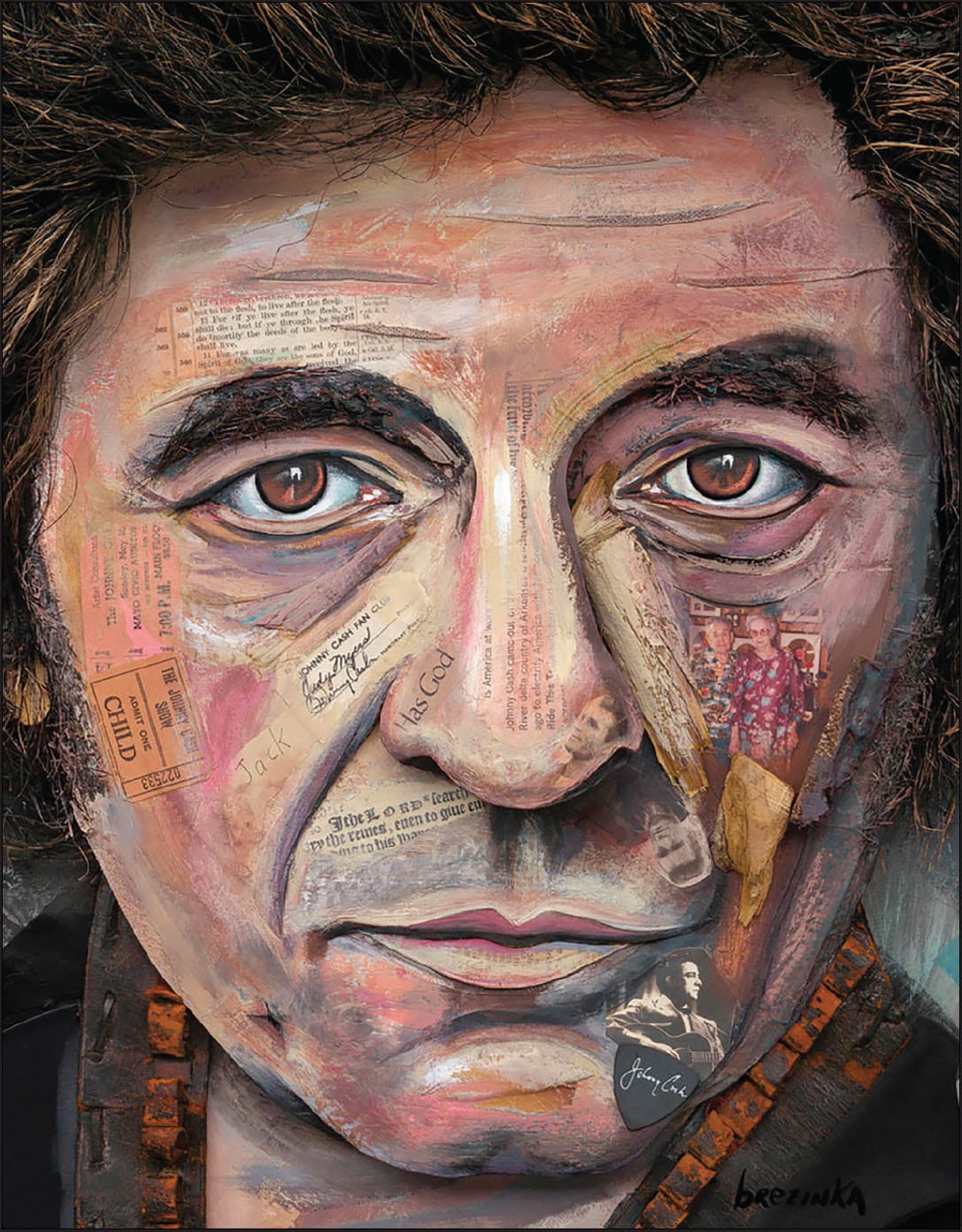

A young Bob Dylan looks back from the concrete-block wall, just a few feet from a three-dimensional portrait of Donald Trump — perhaps the only wall in America the two share. They are feet from a multicolored face of Vincent Van Gogh, sans the ear, the portrait as complex and engaging as Van Gogh himself. A mesmerizing, lifelike human eye on a scrap of paper peers out from between pictures of Johnny Cash and Elvis. A buffalo with a knowing sadness surveys the space.

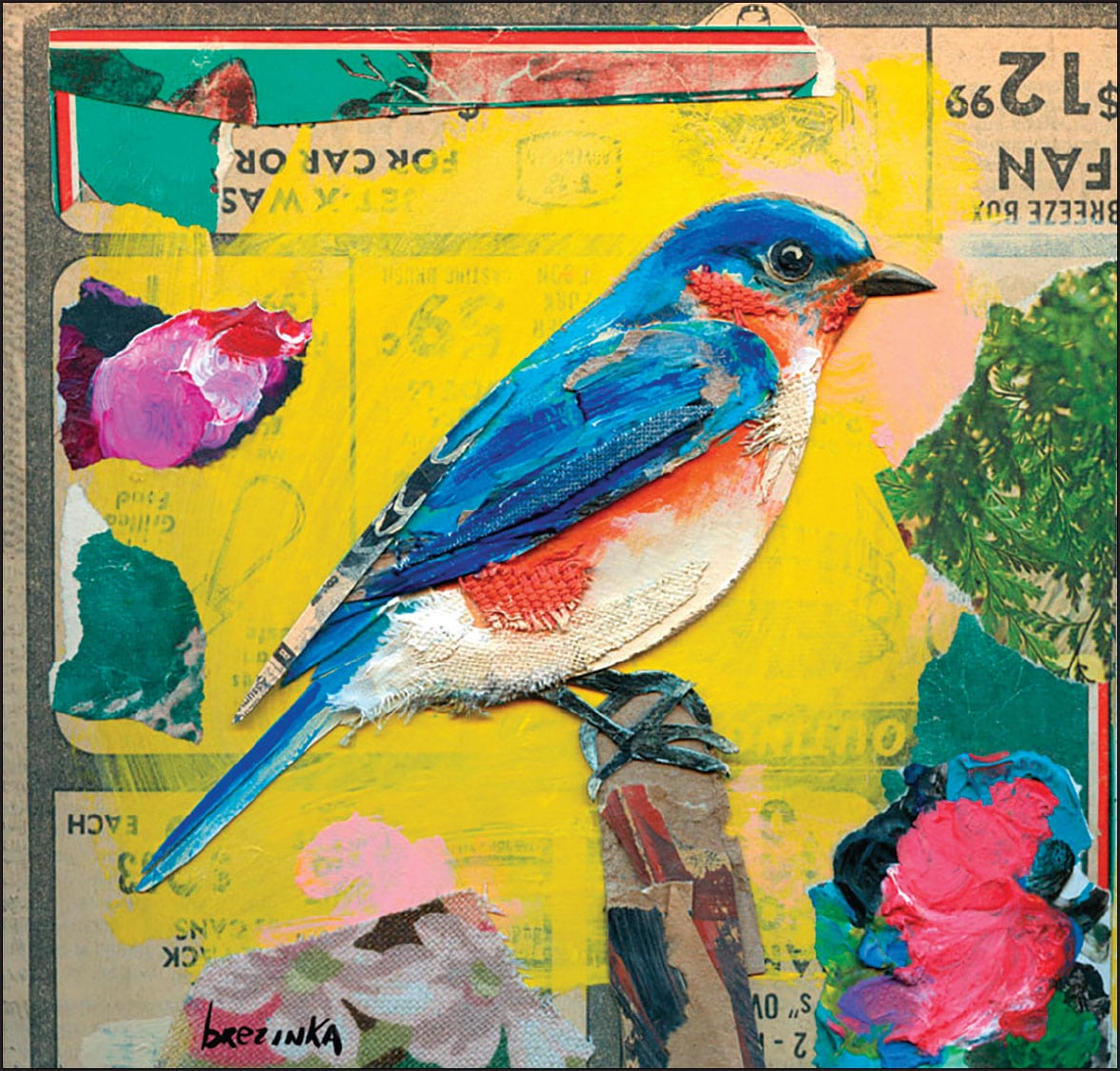

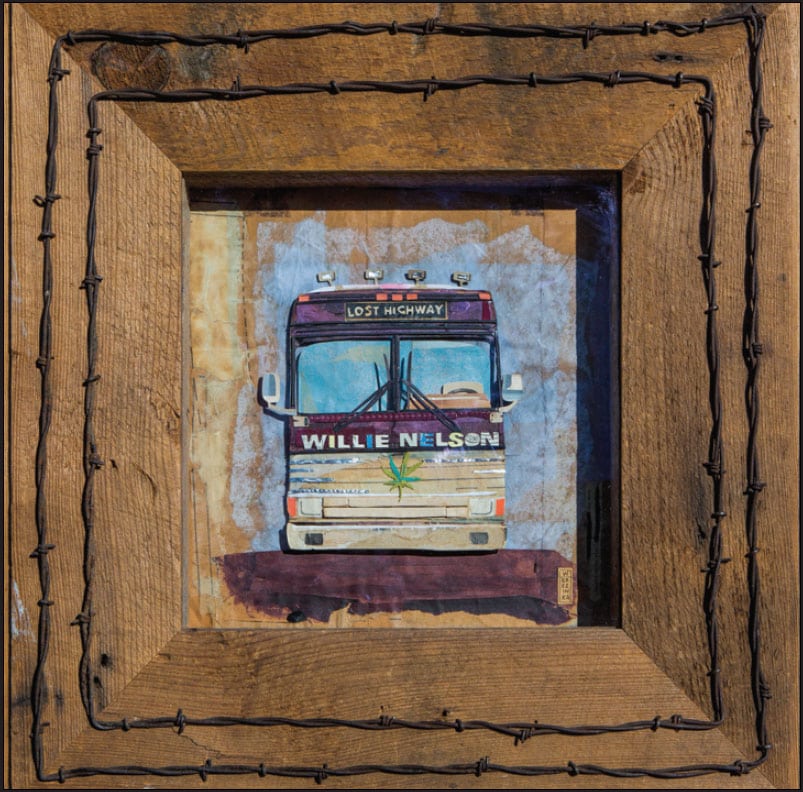

The wall in this Old Hickory art studio mirrors its occupant, artist Wayne Brezinka — an intellectually curious man on the cusp of 50 who creates art that doesn’t fit conventional labels. Without a better descriptor, Brezinka calls his work mixed media, assemblage, 3D and/or collage. His art is created from materials that consume the studio — newspapers, magazines, old books, art supplies, picture frames and all manner of remnants such as string, rope, wire, photos, old envelopes and cereal boxes minus the cereal.

The studio itself is tucked behind another unrelated business. The entrance is in the back rather than the front — appropriately unconventional, a bit of effort required to find it, mimicking the effort needed to find truly exceptional art.

Music plays in the background, again some effort required. It’s not what is popular or expected, but it engages you.

Similarly, Brezinka’s work is immediately engaging, but it is not easy to describe.

“I want people to wonder more about themselves when they view it,” Brezinka says of his creations. “I want them to ask questions and be curious about the world and themselves. There are a lot of different parts and pieces to our lives. I love creating something new that no one else would imagine from discarded items.”

His work is interesting, complex and intellectual. Each truly deserves the overused adjective “unique.” Each captures the essence of the subject. Each makes you think.

It does not translate well to one dimension, however.

“People say they enjoy my work when they see it online,” Brezinka says, “but when they see it in person, it blows them out of the water. It translates so differently.”

Brezinka’s latest work — a portrait of the apostle Paul — is a breathtaking example. Paul looks up from writing, a quill pen in his hand. The apostle’s gnarly beard and receding hairline, created from old-fashioned farm rope and paint, convey his advancing age. One side of the painting fades to black; the other is the particular yellow of natural sunlight as though light is streaming in from an unseen window. Strips of newsprint intertwine with paint and seem perfectly natural as details of the face. Underneath one eye is the word “Christ” in tiny newsprint.

The eyes convey multiple messages — strength, compassion and with the dots of white, a timeless hope. Getting the eyes right is essential.

“I spend a lot of time on the eyes,” says Brezinka, who quotes Irish painter Colin Davison, who said, “You have to nail the eyes.”

Describing the total effect, one Facebook fan put it eloquently: “Your work almost translates the soul of a person, like he is living, breathing.”

Many of Brezinka’s works incorporate original objects of importance to the subject. His portrait of Johnny Cash contains one of Cash’s guitar picks and pictures at different stages of his life. A portrait of Lincoln includes newsprint from his time as well as old photos of slaves.

“The objects complete the piece,” Brezinka says. “In terms of an Elvis or a Johnny Cash, everyone has an image, idea or memory of the person visually burned into his or her mind, but if you look back through history, the person changed every five to 10 years. Photographs and mementos bring it all together. The objects let people in on their inner world as a person.”

Brezinka’s work is increasingly showing up in big-time publications — The Washington Post, The New York Times, POLITICO Europe, Deloitte University Press, The Tampa Bay Times. Former Vice President Al Gore just purchased a piece as did country icon George Strait. His haunting portrait of Lincoln has been hanging in the historic Ford’s Theatre and Museum in Washington, D.C., for five years. It will soon be added to the Smithsonian Institution Catalog of American Portraits Documentation and Research Center.

His work has been recognized by the biggies of the art world as well, including the Society of Illustrators, Communications Arts, Print Magazine and 3×3.

Exhibitions of his work have been held in New York, Nashville, Indiana and Washington, D.C. His 2014 exhibition “Paper Cuts” at O’More College of Design in Nashville had a record-breaking opening attendance.

Behind all the bright lights and big names, though, is a quiet family man — a father of three who misses daughter Abigail out West for college, enjoys his high-schooler, Zach, and picks up his youngest, Andrew, from school at 3:30 every day. He is married to Staci, a therapist who helps those addicted to drugs.

Brezinka rises before dawn several mornings a week to exercise his already fit body. He is a man of faith who experienced gut-retching personal trauma as a child. In short, he is a man as complex as his art, a man who uses that art to convey truth and work through his own truths. He believes deeply in the healing that can be found through art.

“I am drawn to art therapy, to using the arts to get to deeper issues,” Brezinka says. He worked through his own childhood trauma this way.

“When I was 7 or 8, I was molested by a family member,” he recalls. “As a child, you don’t know what to do with that. You can’t process it. The pain is so deep-seated, you can’t tell anyone. The body takes the trauma, hides it and keeps it.”

Art showed Brezinka a way through the pain.

He re-created the nightmare that awoke him on so many nights into a 4-by-5-foot, three-dimensional piece that shows a young red-haired boy in striped pajamas clutching a teddy bear. The boy is in the woods. Alone. At night. Actual tree branches jut out. A snarling animal with piercing eyes is a few feet away. The abuser is right behind the boy, not clearly identifiable but instantly recognizable. The boy is screaming, but there is no one to hear or help.

He soon discovered that the catharsis was not just for him; it would help others, too.

“It is one of my most powerful pieces,” Brezinka acknowledges. “People stand in front of it and start weeping. I have seen the power it has to help people with their own stories.”

Ann Angle, an author in Wisconsin, saw the piece and commissioned a book cover for her work, “Things I’ll Never Say: Stories About Our Secret Selves.”

For Brezinka, the piece helped him dig deeper psychologically and create better work.

“A lot of significant moments in my past caused me to guard myself more and steer how I wanted to be seen,” he says. “Now I have embraced art more. I love what I do. There is such power in art. I am comfortable with what I do and who I am. I am realizing how great a gift art is. It speaks to so many people.”

Brezinka’s pieces typically take months to create, although he completed one in two grueling weeks to accommodate a client. He does not like to be rushed and normally gives no thought to the length of creation.

He begins with a sketch the actual size and appearance of how the finished piece might come together, but it is rarely precise. There are so many pieces to be fashioned together.

“If the work is commissioned, I take direction and try to wrap my mind around what that would look like,” he says. “They usually provide me with an envelope full of material about the subject and sometimes some objects to work with.

“Paul was a commission. They wanted to capture Paul writing, so I started with questions about what Paul looked like (there is no known image) and how I could capture him in that sort of setting.

“I did a lot of research into the history of the subject and studied images. I felt like light would be important in this work, but it is difficult to capture light. It was a really big challenge. I learned by studying and by trial and error.”

“I wasn’t looking for it,” he said of his journey to this medium. “I wasn’t aiming to create work that looked like it. I was just drawn to small pieces of trash on the pavement — rusty nails, metal, so forth. I would scan them into my computer and play around with them.”

Behind that experimentation, though, was a degree in graphic design from Staples Technical College in Minnesota. That training led him to work at an art agency in Duluth, Minnesota.

A passion for music, particularly Christian music, and an intense desire to create album covers led Brezinka to take his first leap of faith and move to Nashville, then and now a mecca for Christian musicians.

“I decided to give it a go,” Brezinka says, “and within three months, I had a job with an ad agency.”

Three and a half years later, a friend who also happened to be the creative director at the prestigious agency EMI approached him about a job there.

Brezinka’s dream job was within his reach. Four interviews later, he landed the job. He was there for four and a half years before taking another leap of faith — this time leaving the security of a steady job to pursue a form of art few knew about.

“The art grew slowly from small images of 4 or 5 inches,” he says. “The three-dimensional aspect has also grown, protruding farther from the canvas over the years.”

Brezinka is now embarking on a project that challenges all artists — a self-portrait. He shares a picture of himself as a freckle-faced child that will be part of the portrait as well as remarkable drawings of animals he created as a child — an orangutan, cats on paper yellowing with age. They are accurate renderings, not the whimsical, stick-figure-type drawings most children make.

The self-portrait might lead to his new dream: winning the Outwin Boochever Portrait Competition and ultimately having a portrait he created hanging in the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C.

Brezinka is also beckoning others into art, offering workshops to help aspiring artists find their creative outlets.

“I am drawn to opening the door for people to create,” he says. “I like being a guide for people to get back in touch with their creative little kid.”

The little kid with red hair and freckles who was hurt so badly as a child is now an adult with a family of his own, immense talent, the freedom to create and a blossoming career. Art has brought him through tragedy to a life he couldn’t even imagine back then.

“I am over being fearful and not really living,” Brezinka says. “I am thankful. I am ready to start digging in and celebrating life. I’m in a really good place.”

Brezinka hopes his art will help others arrive at their good place.

For more on Wayne Brezinka, including information about his workshops, visit waynebrezinka.com.

Old Hickory Centennial Celebration features Brezinka’s work

Once a DuPont company town, Old Hickory is now an area of Nashville rich in history and family tradition. In recognition of its 100th anniversary, the community will hold a three-day celebration June 1-3. Friday will feature an opening concert. Saturday opens with a parade, includes tours and sessions and concludes with a dinner and fireworks. A community worship and picnic highlight Sunday’s activities. Most events are free and open to the public.

Old Hickory resident Wayne Brezinka is designing a time capsule from a compilation of Old Hickory/DuPont memorabilia. When complete, the time capsule will hang at the Old Hickory Community Center.

To find out more, visit oldhickorycentennial.com.