Songwriters from Operation Song go from hitmaking to healing as they co-write with Tennessee’s military veterans with PTSD

Combat veterans will tell you that most battle wounds are invisible. Soldiers carry scars on the inside from wounds sustained at the moment of impact. They entered hell willingly, trained for the inevitable clash of artillery and upon returning home are expected to fall back into their previous suburban lives, tranquil and trauma-free. They are once again mowing their lawns, walking their dogs and going to dinner with their families at their favorite restaurants. Like strange tourists who only visit the troubled and war-torn, many veterans talk about the reverse whiplash of returning home and the disorienting effects of what can seem like time travel in warp speed.

Soldiers may return with medals to indicate their physical sacrifice — a Purple Heart for lost limbs, sustained shrapnel — but many return home in unmeasured psychological pain. The flesh heals, but the soul of a soldier carries within it all the detonation of combat — sight, sound and fury — for years. For some, it never goes away. For a lucky few in Tennessee, they have the opportunity to exorcise some of the pain — with music.

Operation Song, headed by Nashville songwriters Bob Regan and Don Goodman, is here to help.

“We started with a ‘let’s give this a try’ attitude,” recalls Regan, whose award-winning songs have been covered by Keith Urban, Trisha Yearwood, Reba McEntire and scores of others. “We look back on it now with amazement. We’ve co-written over 700 songs at this point, and in some ways, we feel like we’re just getting started.”

Songwriters and organizers of Operation Song collaborate with military veterans on the process of telling their story in song. From left, Al Jarvis, Paul Newby, Steve Dean, Skip Skipper (in back), Roger Rahor and Lee Waters read from an overhead screen while Dean sings the lyrics to “Long, Black Wall,” a song by Newby about what it’s like to see his friends’ names on the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, D.C. (Watch a video of the process at tnmagazine.org/OperationSong.)

Operation Song is a nonprofit organization that survives on grants and donations. A small stipend is paid to the 25 or so participating songwriters to reimburse them for travel, but all writers do what they do free of charge.

“It’s not important that our writers have a military background,” says Regan. “Actually, it’s better if they don’t because we want to tell the vets’ stories. This is about them. We just become their guides, working them through the structure and formula of writing a song and giving them an outlet.”

“This is the best thing I have ever done with music,” adds Don Goodman, whose songs have been recorded by George Jones, Alabama and Steve Wariner, among many others, “but a lot of the healing that happens — it’s not what we, the songwriters, do. It’s vet to vet. By meeting and sharing their stories like this, they end up friends. It’s like they get their platoon back. And that’s an amazing thing to see because so many of these guys have been lost for a long time.”

Songwriter and Operation Song Vice President Don Goodman enjoys a moment of levity with veterans as they sort through ideas. From left are Ira Braden (in back), Paul Newby, Margie Newby, Laura Phillips, Mike Couture, Al Kashimer and Goodman.

Dennis Buchanan, a Vietnam veteran from Mount Juliet and participant in many Operation Song writing sessions, might disagree with Goodman’s humble dismissal: “These guys have written hit after hit after hit, and now they’re giving back. They don’t have to be doing this. Because of Operation Song, I have felt, for the first time in 47 years, that brotherhood I had lost.”

Buchanan was introduced to Operation Song by country music artist Charlie Daniels, for whom he worked, and Daniels’ manager, David Corlew. “PTSD never goes away. And it started really getting to me after I retired. When you slow down, your brain has more time to bring up the past, and it starts overworking. I was waking up two and three times a night with nightmares. I’d have to change my clothes because I was soaked in sweat.”

Buchanan, who celebrated his 45th anniversary with his wife, Kay, in October, had started as a young man to pursue music but quit along the way. “I have five guitars, but I had stopped doing anything. I wasn’t going anywhere. I was trapped.”

“I volunteered at 18,” recalls Buchanan. “I’d hardly ever left Tennessee, and before I knew it, I was getting off a plane in Vietnam. It was 117 degrees, and we were immediately under a rocket attack. I thought I had an idea of what hell was, but I knew right away — this was hell. I was so young, it just whupped me.”

Those who know the tall, barrel-chested Buchanan and his decades-long service to Mount Juliet as a police officer, businessman and economic development adviser might be surprised to hear that he could be “whupped” by anything.

Goodman adds, “I’ve seen these big, tough guys — they’re strong, they’ve been trained for combat — and they’ll just break down. They’ll cry freely, openly. In these writing sessions, they know they’re safe. And those tears bind them together.”

“By writing,” adds Regan, “you’re basically taking the bandage off and rinsing the wound. When we write in these sessions, it can go pretty dark, but we always try to put hope in there, even if there is seemingly none. We get them to look at what they have to be grateful for and put that in each song.”

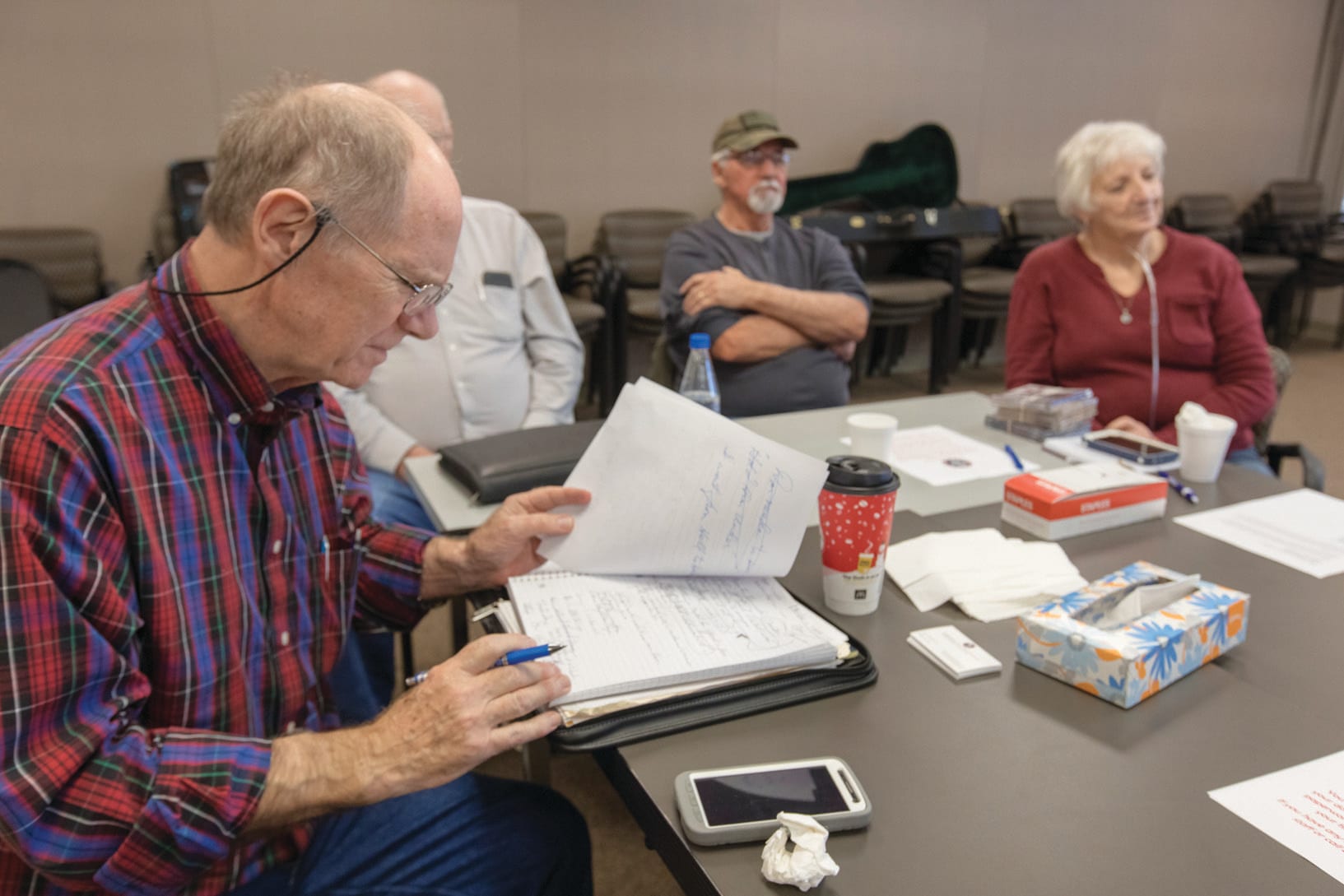

Skip Skipper looks over notes for a possible song collaboration. Boxes of tissues are ever-present at these writing sessions as tears often flow as freely as the laughter.

Forty-year-old Ryan Taylor, an Iraq war veteran who lives in Chattanooga, does not mince words when talking about Operation Song: “It’s a miracle what they do. It really is.”

Taylor is married with five children and seems to have everything to live for, yet he found himself suicidal and inexplicably angry upon returning home. “PTSD robs you of joy. It just steals it away from you, and you can’t explain it to anyone and have it make any sense why you had a gun to your head, wanting to die.”

“Operation Song gets me to quit thinking,” adds Taylor, whose well-crafted rap songs are achingly real and visceral. “I have to stop and come up with rhymes and actually tell a story. It gets me out of my head. And the greatest thing has been to hear another vet’s song and feel exactly what they feel. I have shared stuff in these sessions I’ve never shared with anyone.”

“The transformation of these vets — from who they were to who they are now — is miraculous,” says Al Jarvis, an Operation Song writer and treasurer for the organization. “The process of writing and sharing these songs seems to draw things out of these veterans like nothing else can.”

Regan agrees. “The best compliment I have ever been given was to be called a ‘sin-eater.’ An Army chaplain told me that’s what we do by helping them dissolve some of their darkness.”

David Kent, a Nashville songwriter with hits by Blake Shelton, Lari White and Tracy Lawrence, to name a few, says the vets are not the only ones transformed. “We who write these songs as a part of our daily routine are often the last ones to recognize how crazily influential and powerful a song can be. Operation Song has given me a renewed respect for the sacrifices our military men and women — and their families — make on a regular basis.”

Operation Song President Bob Regan Photo courtesy of operationsong.org

“We aren’t therapists,” adds Jarvis. “In fact, we break all the rules of therapy by giving out our personal cell phone numbers. I’ve gotten calls at 1 in the morning — just a vet who needed to talk — and because we bonded over this music, he felt safe to do that. I love working with these people; they’ve become my family. I retired last year just so I could do this full time.”

The ripple effects of Operation Song will doubtless be felt for generations to come. Family members regularly express their appreciation to Regan, Goodman and the other writers, giving their accounts of dealing with PTSD in their own ways.

“I’m in college now,” adds Taylor. “I have two kids in college, and my wife is in college. I feel the possibilities are endless. But I still feel nervous because PTSD can sneak up on you. But we just keep going one day at a time.”

He takes a deep breath and sighs thoughtfully.

“But I know for a fact there are people alive today because of Operation Song.”

If you would like to support Operation Song or buy the music, or if you know of someone who might benefit from writing sessions, go to operationsong.org.

To hear the songs of the vets featured in this article and to watch a video of a recent writing project, go to tnmagazine.org/operationsong.