“Since evolution proves that all animals progress towards a better species, and since humans are members of the animal kingdom, we should weed out the undesirables in the human gene pool by making sure that people of inferior races, who have diseases or disabilities, or who demonstrate low morals are not allowed to breed.”

I suspect this sentence offends quite a few readers. It reflects the theory behind eugenics — the belief that society should take steps to control its breeding to improve the human race. Many of the policies undertaken by the Nazi party during World War II, most notably the mass slaughter of at least 6 million Jews, started with the twisted logic of eugenics.

This summer marks the 94th anniversary of the Scopes Trial — an event that just about every U.S. history student in America learns about. As books and textbooks tell you, the Scopes Trial was about evolution versus the Bible, the theory that humans evolved from a lower form of animal versus the Biblical account of the creation of the world in Genesis. The trial between the state of Tennessee and a 24-year-old teacher named John Scopes was one of the first legal proceedings broadcast on radio to a national audience. It raised the science-versus-religion debate from scholarly texts to popular culture, and it hasn’t left that stage since.

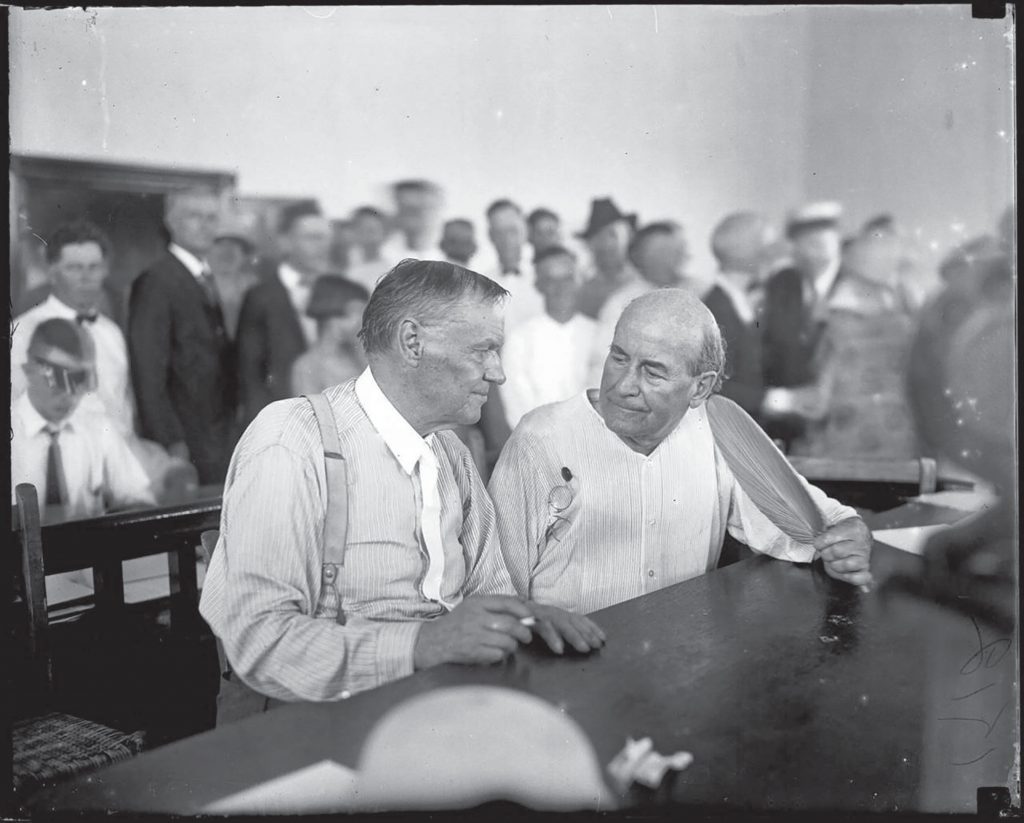

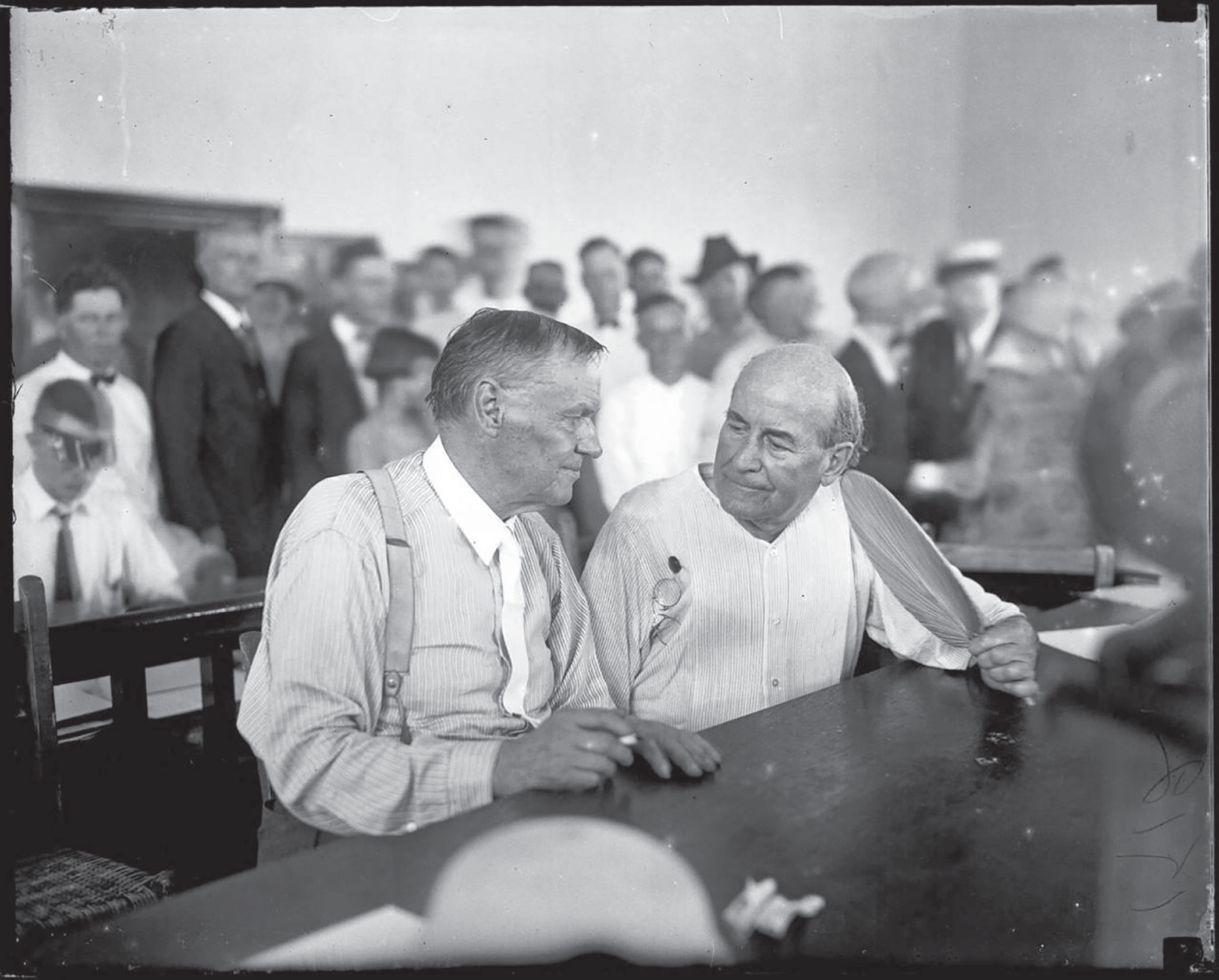

Clarence Darrow, left, and William Jennings Bryan, with fan, at the Dayton, Tennessee courthouse on a hot, humid day in July 1925. The staged trial pitted pro-evolution modernists against fundamentalists, whose human origin theories came from the Bible. The Scopes trial turned out to be one of the most sensational cases in 20th-century America, making Bryan, the Nebraska-born attorney-turned-politician, even more of a household name. He died in Tennessee within days of the trial’s completion. Ohio-born Darrow, known for his fierce defense of civil rights, died in 1938. Both were quoted as being in support of eugenics.

More than a generation after the trial came the release of a movie called “Inherit the Wind” that was roughly based on the events surrounding the Scopes Trial. A lot of teachers show the film to their students, which adds to some present-day oversimplification about what really happened in the summer of 1925 in Dayton.

“Inherit the Wind” is about a teacher who is jailed by an angry public for teaching evolution and who is hissed at and booed wherever he shows his face in public. In truth, John Scopes was well-liked in the community and never spent a day in jail. Scopes agreed to challenge Tennessee’s 1925 evolution law because he was talked into it by a group of business leaders who thought the publicity surrounding such a case would be good for business. They were inspired to do this by the American Civil Liberties Union, which ran an item in the Chattanooga newspaper in search of a plaintiff.

The characters in “Inherit the Wind” argue a lot about science and evolution. At no point does the subject of eugenics come up in the movie. But it should have.

You see, in the late 1800s and early 1900s, evolution and eugenics were linked in so many articles and lectures that there was an assumption that one led to the other. The logic of eugenics goes as follows: All animal species, including humans, have adapted and improved from a lower form to a higher form. It should be obvious that certain human traits (good health, athletic ability, intelligence, even moral behavior) are superior to others. That being the case, it is, at the very least, incumbent upon society to see to it that humans with certain traits do not reproduce.

By 1920, at least 30 states (not including Tennessee) had eugenics laws that required the sterilization of people who were determined as unfit, including “criminals, idiots, imbeciles and rapists.” Today we estimate that about 60,000 Americans were sterilized because of these various state laws. Many states also refused to issue a marriage license to a couple who did not have a certificate from a physician or professional eugenicist stating that neither person had any undesirable qualities reflected in his or her bloodline.

Tennessee’s 1925 evolution law, known as the Butler Act, made no mention of eugenics. It forbade the teaching of “any theory that denies the story of the Divine Creation of man as taught in the Bible, and to teach instead that man has descended from a lower order of animals.”

Some of John Scopes’ students were called on to testify at the trial. High school student Howard Morgan, age 14, sits on the witness stand and testifies against his teacher, saying Scopes taught the theory of evolution in class, an act made illegal by Tennessee’s newly instated Butler Act of 1925. It was an allegation Scopes denied. He did believe in evolution, however, and therefore Scopes agreed to take the pro-evolution role in the trial. A jury of local church-goers took only nine minutes to deliberate a verdict of guilty. As the trial was designed largely as a media event, Scopes never spent a day in jail but was fined $100 — about $1,500 in today’s money.

Scopes admitted to having taught lessons from George William Hunter’s textbook, “A Civic Biology.” I bought a copy at a used bookstore and will admit that some of its contents surprised me. Hunter divides mankind into five races: Ethiopian, American Indian, Mongolian, people from the Pacific Islands and “the highest kind of all, the Caucasians, represented by the civilized white inhabitants of Europe and America.” In a later section of the book, Hunter discusses what should be done to a human with inferior qualities:

“If such people were lower animals, we would probably kill them off to prevent them from spreading. Humanity will not allow this, but we do have the remedy of separating the sexes in asylums or other places and in various ways preventing intermarriage and the possibilities of perpetuating such a low and degenerate race. Remedies of this sort have been tried successfully in Europe and are now meeting with success in this country.”

John Scopes stands between two well-known attorneys of the day, Dudley Field Malone, left, and Clarence Darrow, right, outside the Dayton courthouse in 1925. After the trial, Scopes left teaching to pursue a career in geology and worked in the oil industry. He eventually moved to Shreveport, Louisiana. He wrote “Center of the Storm: Memoirs of John T. Scopes” in 1967 and passed away at 70 years of age in 1970.

“Eugenics Helping in Reduction of Number of Crimes, Experts Say,” claimed one Nashville Tennessean headline in 1923.

By the 1920s, eugenics was such a popular concept that many Americans believed that an emphasis on it would eventually rid society of all of its evils. “Eugenics Helping in Reduction of Number of Crimes, Experts Say,” claimed one Nashville Tennessean headline in 1923.

Four-time presidential candidate William Jennings Bryan was one of the attorneys representing the state in the Scopes Trial. Bryan wrote a 12,000-word closing argument that summarized his objections to evolution and the conclusions many social scientists had formed as a result. Since defense attorney Clarence Darrow waived his right to make a closing statement, Bryan was not allowed to deliver his, but you can read Bryan’s closing argument on the internet. Although Bryan never intended to use the word “eugenics,” he does allude to it in sections that describe the “cruel” and “bloody” impact that evolution was already having on the culture of America. “Science is a magnificent material force,” he wrote, “but it is not a teacher of morals. It can perfect machinery, but it adds no moral restraints to protect society from the misuse of the machine.”

During the Nuremberg Trials that followed World War II, Nazi defense attorneys claimed that the original idea of the Holocaust came from eugenics theory and practice, quoting a 1927 U.S. Supreme Court decision that ruled in favor of state-mandated sterilization of the “unfit.” Because of this and other reasons, eugenics fell out of favor in the United States. Many science textbooks still teach evolution, of course, but they no longer use the theory of evolution to argue in favor of social policies based on eugenics. Today most Americans are unaware that the two concepts were ever so commonly connected, and most Tennesseans do not know that the matter of eugenics was in the back of the mind of everyone associated with the Scopes Trial.