I was recently driving through Smith County on Highway 70 when I did a double take. I pulled over, turned the car around and went back to see if I’d imagined what I’d seen. Sure enough, it was an old, rusty ferry parked on the south bank of the Cumberland River.

The ferry got me thinking. Before there were bridges across every river and before people took interstates, life moved at a slower pace. As recently as the 1950s, it would have been difficult to travel from one part of the state to another without having to ride a ferry along the way.

In early Tennessee history, ferry operators were prominent people on whom everyone relied. Without the ferry, people couldn’t get to the courthouse, farmers couldn’t get their livestock to market and kids couldn’t get to school.

Since ferries were a matter of public safety and since the setting of ferry rates would have affected everyone, ferries were regulated. Ferry operators had to get licenses that addressed how much they could charge, what hours they worked and liability in case of an accident. The license also prohibited a competitor from opening another right next to the licensed ferry.

Once a ferry license was granted, a family might continue to operate it for decades — and even generations. That’s why some of these families are still immortalized in street names.

Every river — large and small — had ferries. Early Tennessee migrants used Clark’s Ferry to cross the Clinch River at Fort Southwest Point (later Kingston). Travelers on the Natchez Trace crossed the Duck River on Gordon’s Ferry.

According to an 1878 map, there were at least nine ferries across the Cumberland River in Sumner County alone, the best known of which was Wood’s Ferry, south of Gallatin. In the 1920s, there were more than a dozen ferries crossing the Mississippi River from Tennessee into Arkansas and Missouri.

Matthew Rhea’s 1832 map of Tennessee shows at least 10 ferry crossings between Knoxville and present-day Chattanooga. Some are labeled with names such as Locke’s Ferry in Rhea County and Blythe’s Ferry in Meigs County (which was one of the gathering points for Cherokee Indians forced to migrate west during the Trail of Tears). The map shows about the same number of ferry crossings on the Tennessee River on the other end of the state, with names such as Patterson’s Ferry in Perry County and Gray’s Ferry in Stewart County.

In the 1800s, most ferries consisted of little more than rafts that were pulled from one side of the river to the other by men or mules. In other cases, horses with blinders over their eyes (so they wouldn’t get dizzy and fall) stood on the ferries and walked on a treadmill that propelled the boat forward.

Gas-powered ferries began replacing the horse and mule ferries in the early 1900s. But in 1953, a ferry in Hawkins County was still being pulled from one side of the river to the other by the elderly man who operated it.

As roads and infrastructure improved across Tennessee, bridges replaced ferries. However, Tennessee still had more than 800 operating ferries in 1930 — by which time their operation was overseen by the Tennessee Highway Department. That number decreased rapidly over the next few decades as the state executed a deliberate plan to replace ferries with bridges financed by tolls. In some cases, the demise was high-profile enough to make news.

The ferry crossing the Holston River at the Hawkins County town of Surgoinsville was replaced by a bridge in 1955.

The ferry that crossed the Mississippi River and connected Tiptonville to Portageville, Missouri, closed in 1976.

The Kingston Ferry closed in the late 1980s after nearly 200 years in continuous operation.

Finally, the Washington Ferry that crossed the Tennessee River and connected Rhea County to Meigs County closed in 1996.

As you can see from the 1950 photo, Grainger County’s Blount Ferry was pretty small.

Today it is easy to get sentimental about the days of ferry travel. Truth be known, many of Tennessee’s ferries were small, rickety operations that didn’t exactly give the traveling public a feeling of confidence. Ferries also sometimes sank, and, indeed, there were quite a few deadly accidents and drownings associated with ferries.

In 1950, a Knoxville Journal reporter had this to say about taking a car across the Holston River on Boyd’s Ferry: “When the motorist does see the contraption that passes for a ferry, if he hasn’t lost heart by then, he usually has to wait a trip or two for the cars and trucks already ahead of him. Then to drive on the ferry, he is forced down a steep, rutty descent of loose stone and wonders if he will ever make it.”

In the 1920s, drivers between Knoxville and Chattanooga had to take Blair’s Ferry across the Tennessee River at Loudon. It cost 25 cents per car and driver and 5 cents for each additional passenger. The ride on Blair’s Ferry might not take long, or you might wait in a line behind 10 cars. If the river was too high, drivers might get stuck overnight. “Hotels, rooming and boarding houses are taxed to capacity and many travelers seek shelter in private homes,” reported the Knoxville Journal in 1927 when Blair’s Ferry had to be closed because of high, fast-moving water.

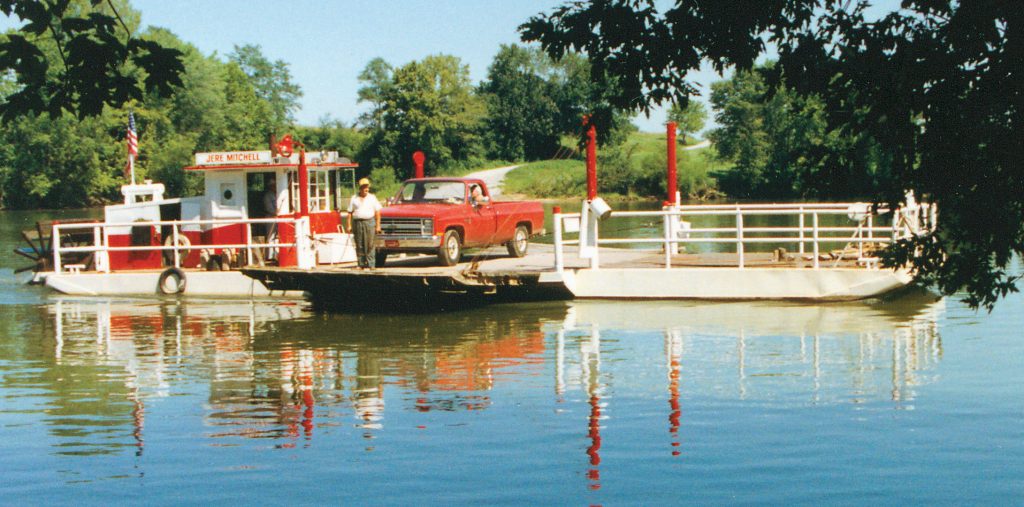

The old Rome Ferry sits beside the Cumberland River in Smith County.

In 1929, the state opened a toll bridge across the river adjacent to Blair’s Ferry. For the next several years, travelers could either pay to ride the ferry or pay a slightly higher fee to cross the bridge.

After World War II, state law eliminated toll bridge fees, shutting down Blair’s Ferry once and for all. On that day in 1947, a reporter for the Knoxville News Sentinel said that all the car drivers were smiling the toll booth and the ferry were closed. “Hallelujah!” shouted one driver.

However, Augusta Long, an 80-year-old lady who had lived beside the ferry landing her whole life, had a different view. “It was here when I was a little girl,” she said. “I’m gonna miss the old boat.”

Today, ferry travel is practically a thing of the past. According to the Tennessee Department of Transportation, the only ferries that still operate in the state are in Stewart County (at Cumberland City) and Houston County (at Danville).

By the way, I checked. The rusting ferry on the side of Highway 70 in Smith County operated until 1992, when its last pilot died. From newspaper clippings, I determined that there was an attempt by locals to bring it back, organized under the name Friends of Rome Ferry. But nothing came of it. Given its condition today, we can safely say that it will never again float the Cumberland River.

Four men cross the Cumberland River at the Brooks Ferry in Clay County in 1950.