Art has a way of telling a story that is often unexplainable. It’s about emotions, those states of mind — and of the heart — that are hard to put into words. Art reveals our joys and our sorrows, the beauty of the world as well as its dark side, and everything in between. Such is the case for an upcoming exhibit focusing on the experiences of two Vietnam War veterans.

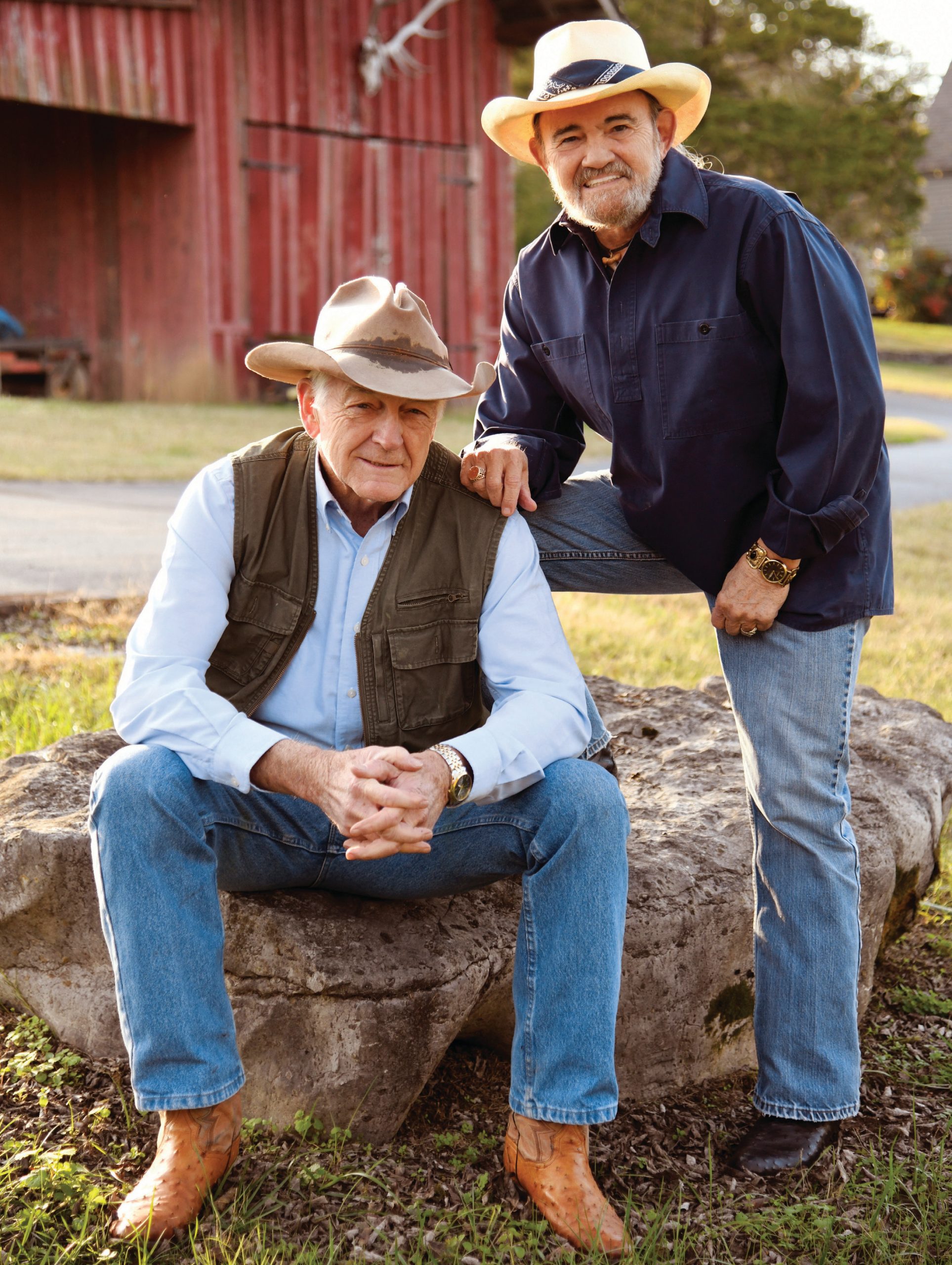

David Wright, seated, and Chuck Creasy didn’t know each other as soldiers in Vietnam but became fast friends when they met after the war while both starting careers in the commercial art field. They are co-hosting an art exhibit focusing on the land they and many of their fellow veterans still visit in their memories and dreams.

“Vietnam: 2 Artists, 2 Soldiers, 2 Journeys, Then and Now” will open Aug. 2 and run through Sept. 20 at the Monthaven Arts and Cultural Center (MACC) in Hendersonville with a VIP fundraising event on Aug. 1 at 6:30 p.m. In the free public exhibition, artists David Wright and Chuck Creasy will be displaying photographs, sketches and paintings from their tours of duty in Vietnam as well as Creasy’s paintings inspired by a return trip to the country 50 years later.

Wright says that when he saw Creasy’s Vietnam paintings, he pulled out his own artwork he’d done while a soldier there. He hadn’t looked at it in years. He had put it all away in a box when he was discharged.

“It dawned on us both that we had a story to tell that spanned 55 years,” Wright said, “just like the title of the exhibit states.”

From the war-torn jungles of Vietnam to the peaceful hills of Sumner County, these artists document the world as they’ve seen it — and raise money for veterans along the way.

Story by Trish Milburn • Photographs courtesy of David Wright and Chuck Creasy

Birth of an exhibit

They pitched the idea of a joint exhibit to Cheryl Strichik, MACC director, and she thought it had merit.

“It sounded tremendous, like a perfect art installation topically and visually for our veterans’ exhibits,” Strichik says.

“When we learned that Monthaven already had a veterans outreach program in place and a building called Liberty Hall on the drawing boards, the exhibit became more than the ‘Chuck and Dave show,’” Wright says. “Hopefully, the show will go on the road to bring attention to the veterans’ connection and maybe even raise some funds for Liberty Hall construction and the veterans’ programs.”

Wright says two museums have already reached out with interest in hosting the exhibit after its Monthaven run.

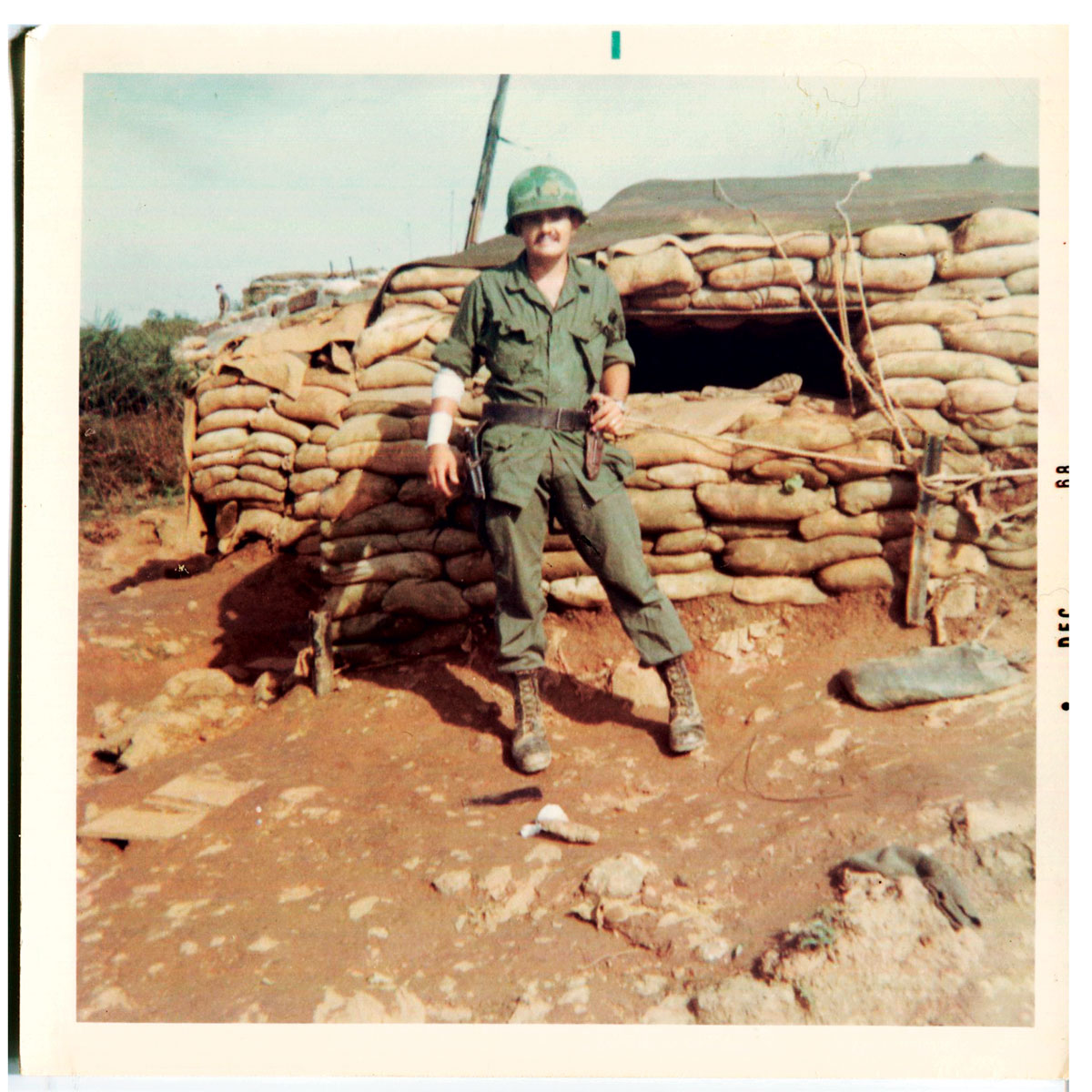

David Wright in the highlands of Duc My, 1965.

The Liberty Hall that Wright mentions is a planned 60,000-square-foot, state-of-the-art facility, a three-story complex to include a theater, café, interactive children’s area, sophisticated information kiosks and multiple galleries. It will hold permanent, rotating and touring American and Western art exhibits as well as being a showcase for art created by veterans. Built on some of the last remaining Revolutionary War land grant property in Tennessee, it will be the largest U.S. museum featuring artwork by military veterans.

The MACC has an active arts program for veterans called Between the Lines, which includes free art classes in various media. The completion of Liberty Hall will allow more outreach in partnership with CreatiVets, a Nashville-based nonprofit that uses songwriting and visual arts as therapy for vets with post-traumatic stress disorder, traumatic brain injuries or other injuries resulting from their military service.

Two paths converge

Their paths toward this creative collaboration began back in 1964, when Wright was drafted into the Army. After basic training, he was sent to Fort Gordon in Georgia where the Army put his artistic skills to work, but when he learned of the war going on in Vietnam, he volunteered to serve there. He arrived in-country in December of 1964. He was classified as an advisor in Military Assistance Command Vietnam (MACV) and worked with the Vietnamese Army, ARVN (Army of the Republic of Vietnam). His one-year tour of duty was spent as a door gunner in a Huey gunship.

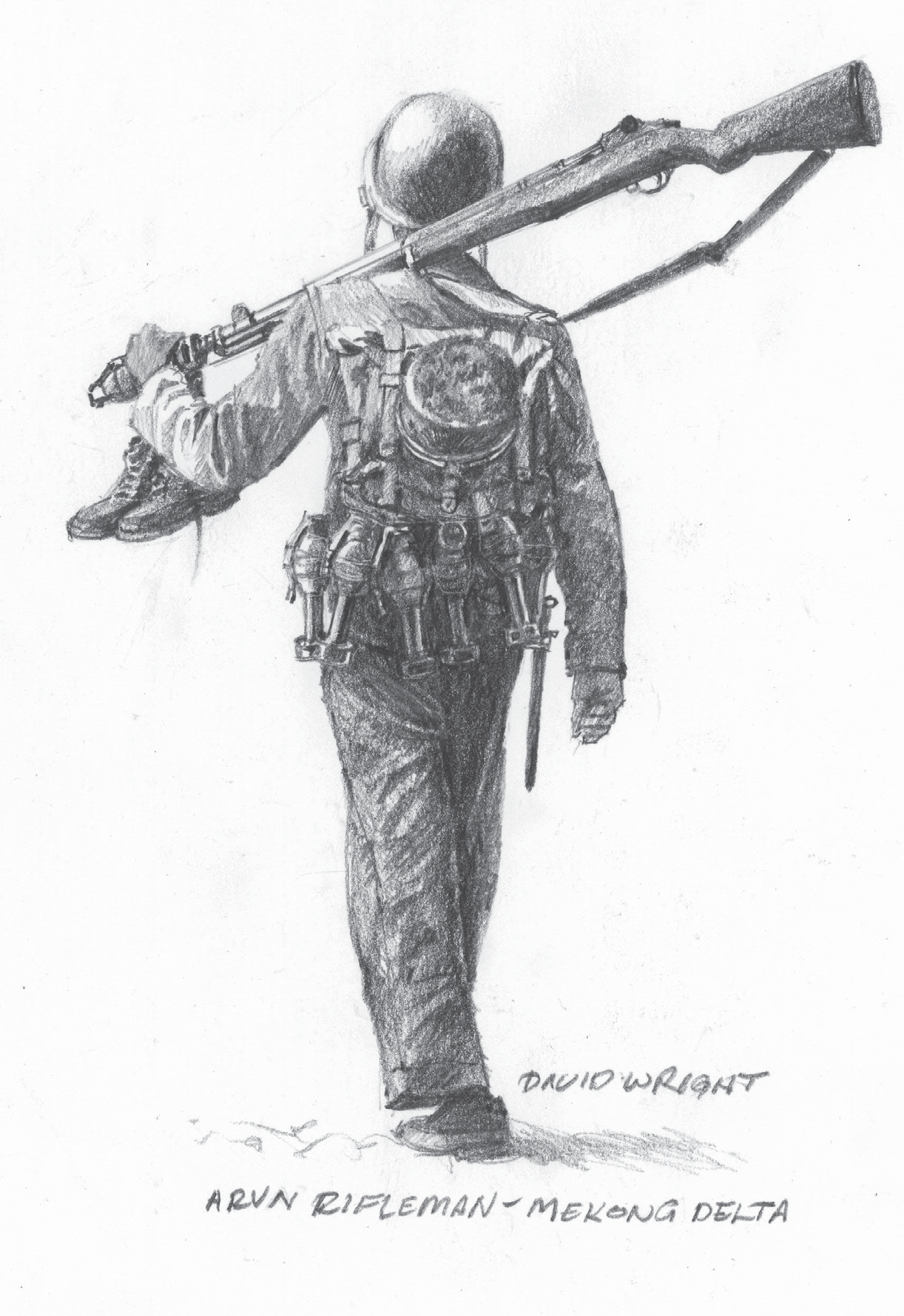

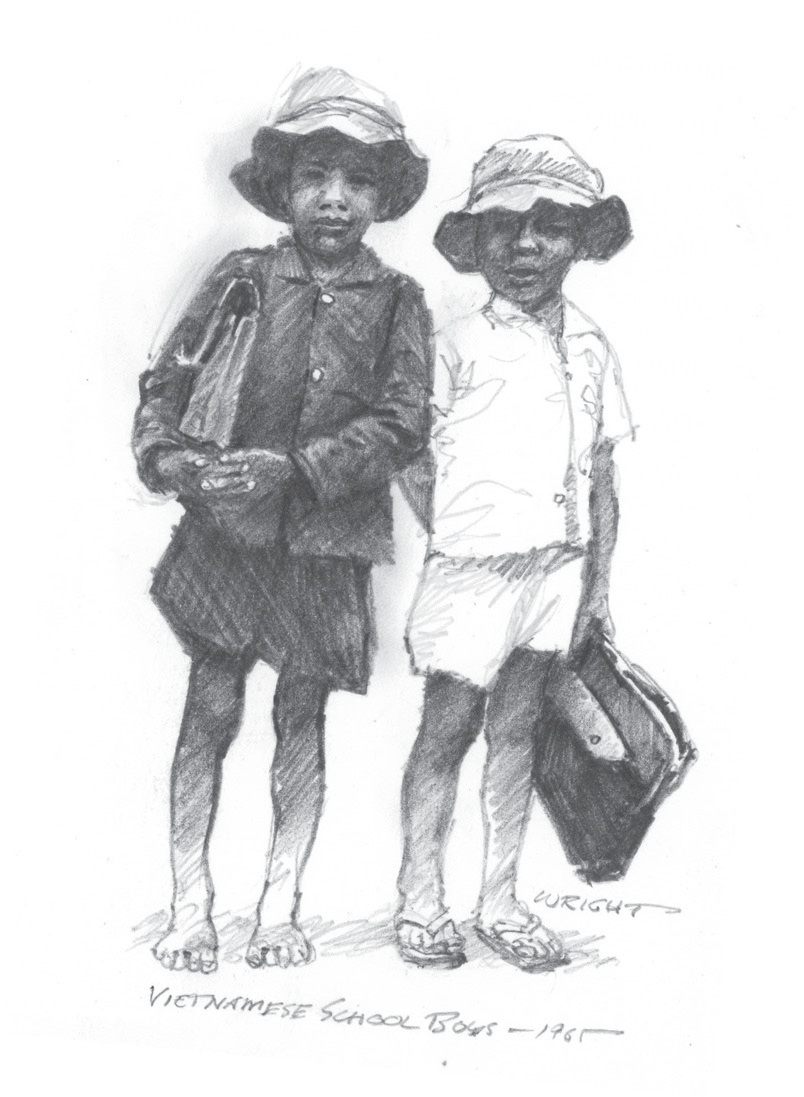

Despite being a soldier, Wright’s artistic eye was still very much in use during his time in Vietnam. His contributions to the exhibit include sketches, drawings and a few paintings he did while in Vietnam and after returning home from photos he’d taken there.

“I have around 36 pieces in the exhibit,” Wright says.

“My focus was on the people and country: ARVN soldiers, American soldiers, the people and Montagnards, indigenous people I served with in the highlands who fascinated me by how similar they were to our Native Americans of the 18th century. So you will see mostly black-and-white images of my art, which melds with Chuck’s rich, full-color paintings done 50 years later. It’s a nice contrast — the war 55 years ago in black and white and the country today in full color.”

“Fishing Boat — HaLong Bay” from Creasy’s return trip to Vietnam will be one of many paintings from that trip on exhibit at Hendersonville’s Monthaven Arts and Cultural Center Aug. 2-Sept. 20.

Wright and Creasy also will exhibit photos that were made in-country during their tours.

“I photographed as often as I could,” Wright says. “Here, again, I focused on the people mostly. My art is not considered ‘combat art’ at all. I was trying to record the human side of the people, the country and what I saw outside of the war ravaging the countryside. Vietnam was a beautiful country.”

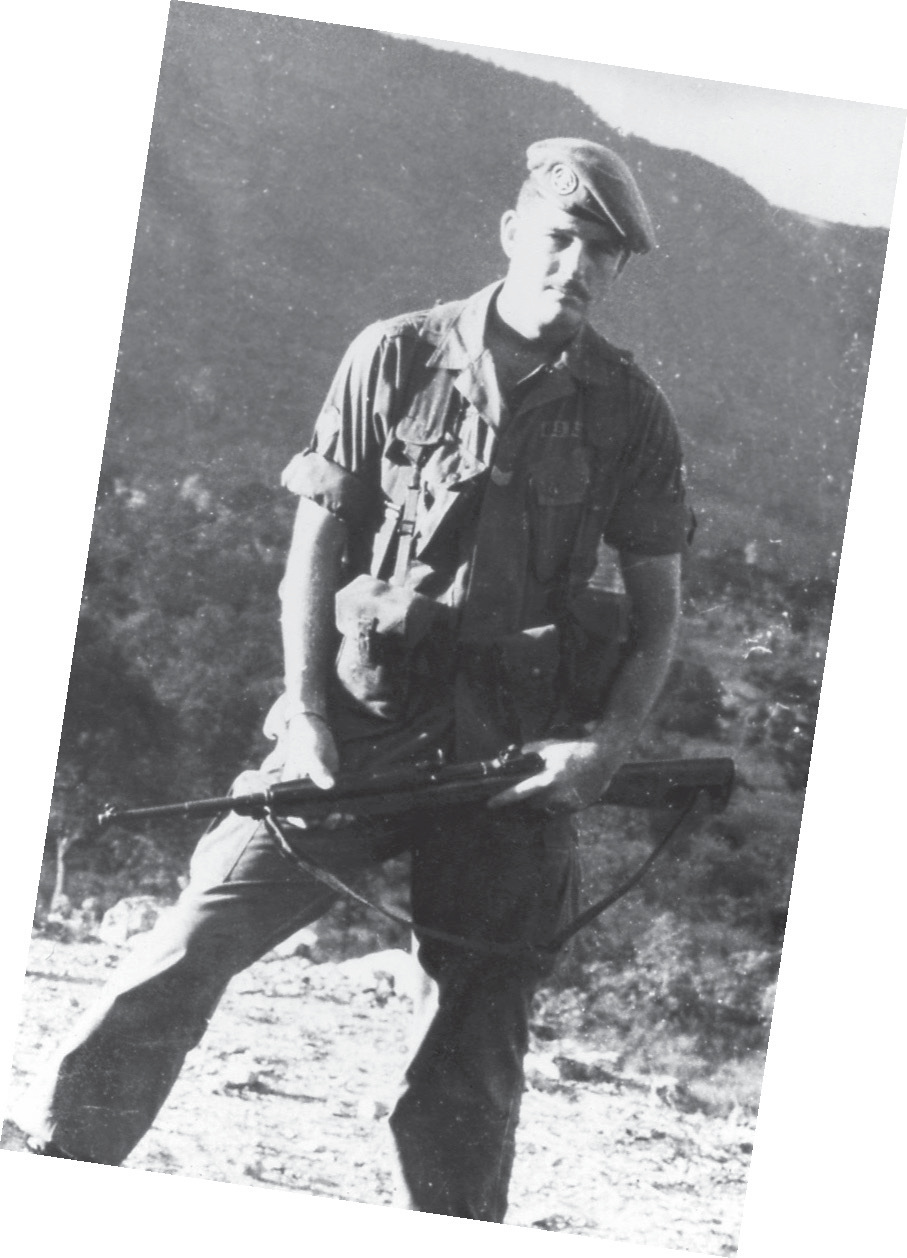

Creasy’s journey to Vietnam came a bit later and included training at Officer’s Candidate School in Fort Sill, Oklahoma, from which he graduated a second lieutenant. A year later, he received orders to go to Vietnam and arrived there in October of 1968, serving as an artillery forward observer. That assignment meant he would spend at least three weeks of every month in the bush, sleeping on the ground, seeking out the North Vietnamese Army and Viet Cong to neutralize them.

David Wright stands among his work in his studio. Wright has always been fascinated with history and the American frontier and reflects that in his oil paintings, which have won multiple awards and honors.

“It was a nasty assignment, especially since the life expectancy of a forward observer attached to an infantry company was a mere two and a half weeks,” Creasy says. During his stint, Creasy suffered through malaria, jungle rot and dysentery but wasn’t sent home until he broke his foot.

Once home, Creasy enrolled in the Harris School of Art, where Wright was attending. They became friends and worked on a variety of projects together during their graphic arts careers until Wright became a full-time painter in 1978.

Return to Vietnam

“Going back to Vietnam had always been something I felt I needed to do,” Creasy said. “The country and its people I had encountered while there in the midst of war had made a deep and lasting impression on me. The people I met there were primarily rice farmers, small shopkeepers and country families torn apart by a war that had ravaged the beauty of the lush triple canopy jungles in the majestic mountains. It was traversed by rivers, streams and lakes that gave way to beautiful beaches on the South China Sea. It was a land of blue and green, inhabited by a people as lovely as the land, a people who were humble, kind and respectful even though devastated by centuries of war. I felt a need to return and see how these people and their land had endured this last war.

Creasy’s water-color of a girl on the Thu Bon River in Ho An from his return visit to Vietnam in 2018.

“What I found was truly amazing, and I felt compelled to try to capture that recovery in paintings that were inspired by sketches and photos that were done on that trip back. This process has helped me forget some of the horrors of war I experienced while there in 1968 and 1969 and to marvel at the resiliency of the human spirit and the desire we all carry within us to live happily and in concert with our world.”

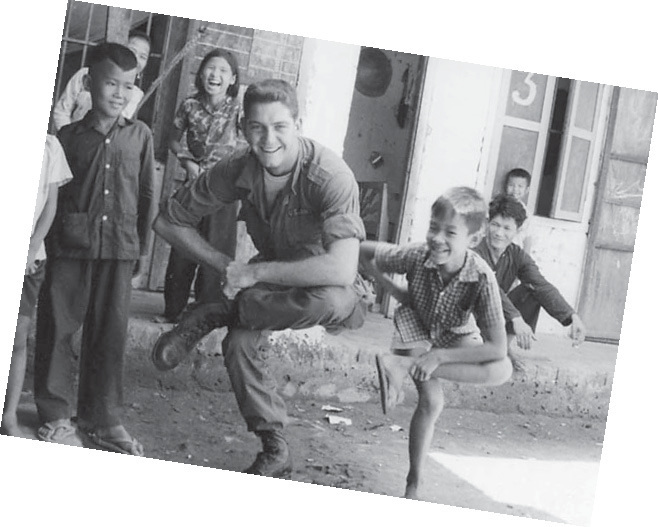

In addition to their artwork, Wright’s and Creasy’s photos from their time in Vietnam serve as snapshots not only of a time and place but also people with their own stories. In one of Wright’s photos, a Vietnamese man holds his small son. A few weeks later, that man was killed in a firefight, leaving the little boy to grow up without his father. In a happier photo, Wright stands on one leg alongside a boy doing the same.

“I was always impressed that these kids had seen nothing but war their whole lives and yet always seemed cheerful,” he says. “They had learned to adapt to that circumstance.”

The opening weekend of the exhibit at MACC will feature more than Wright’s and Creasy’s contributions.

“We’ll have a war-era Huey UH1B helicopter come in on opening weekend. It flew in Vietnam from 1962 to 1971, and it will be piloted by two Vietnam vet helicopter pilots,” Wright says. “They’re Robert Curtis and Mike Holcomb, and they both have stories to tell. Robert Curtis has written two books about his exploits, and Mike Holcomb flew one of the last helicopters out when evacuating the embassy.”

Though more than five decades have passed since Wright and Creasy were soldiers in a faraway land, they know the memories for lots of vets are still fresh and often traumatic.

“I have deep respect for the men and women who have answered the call to serve, and I hope that my humble attempt to shed some light on how Vietnam and its people have come back will somehow soothe spirits and bring healing and a peaceful closure,” Creasy says.

Getting there

The Monthaven Arts and Cultural Center, housed in the circa 1863 Monthaven Mansion, is located at 1017 Antebellum Circle in Hendersonville. For more information, visit monthavenartsandculturalcenter.com or call 615-822-0789. Admission is free, but donations are always welcome. To learn more about David Wright’s and Chuck Creasy’s other artwork, visit their websites at davidwrightart.com and fineartamerica.com/profiles/chuck-creasy.

Note:

As this article is being written in May while the COVID-19 pandemic is still of great concern and social distancing is in place, please verify that the exhibit is still on for the dates mentioned before traveling to see it.