I’ve come to believe that the oversimplified version of history told in textbooks and on historical markers is less interesting than the accurate and complex version that really happened. As we celebrate Tennessee’s passage of the 19th Amendment, here are some examples of what I’m talking about:

1 In the summer of 1920, Tennessee women were already allowed to vote.

Women across America fought for the right to vote for several generations. Shortly after the Civil War, an organization called the American Woman Suffrage Association began fighting for woman suffrage on a state-by-state basis.

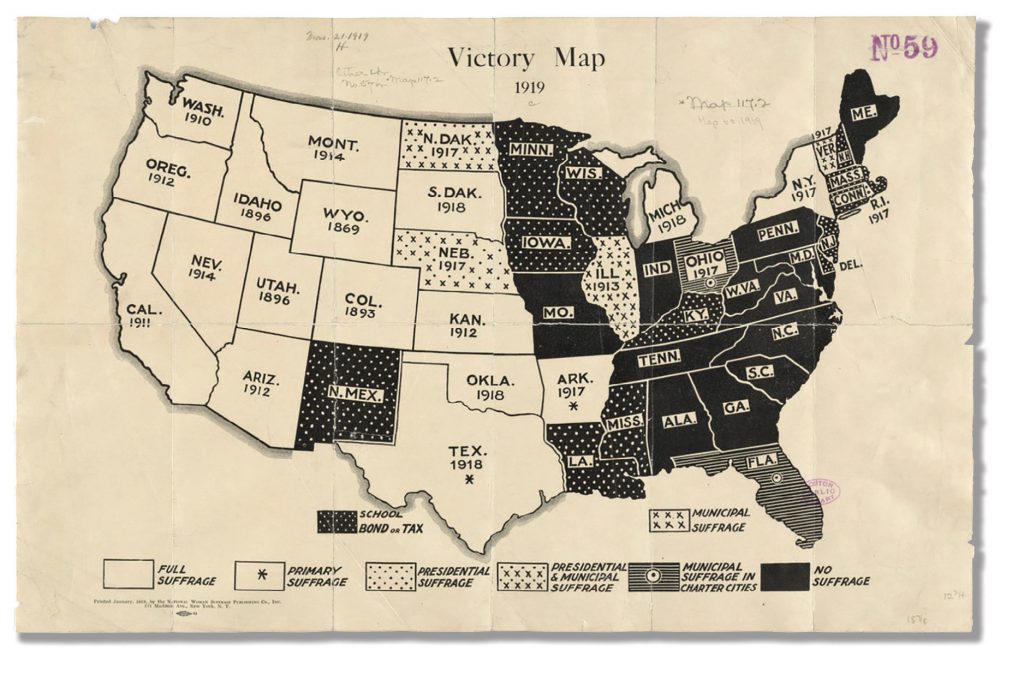

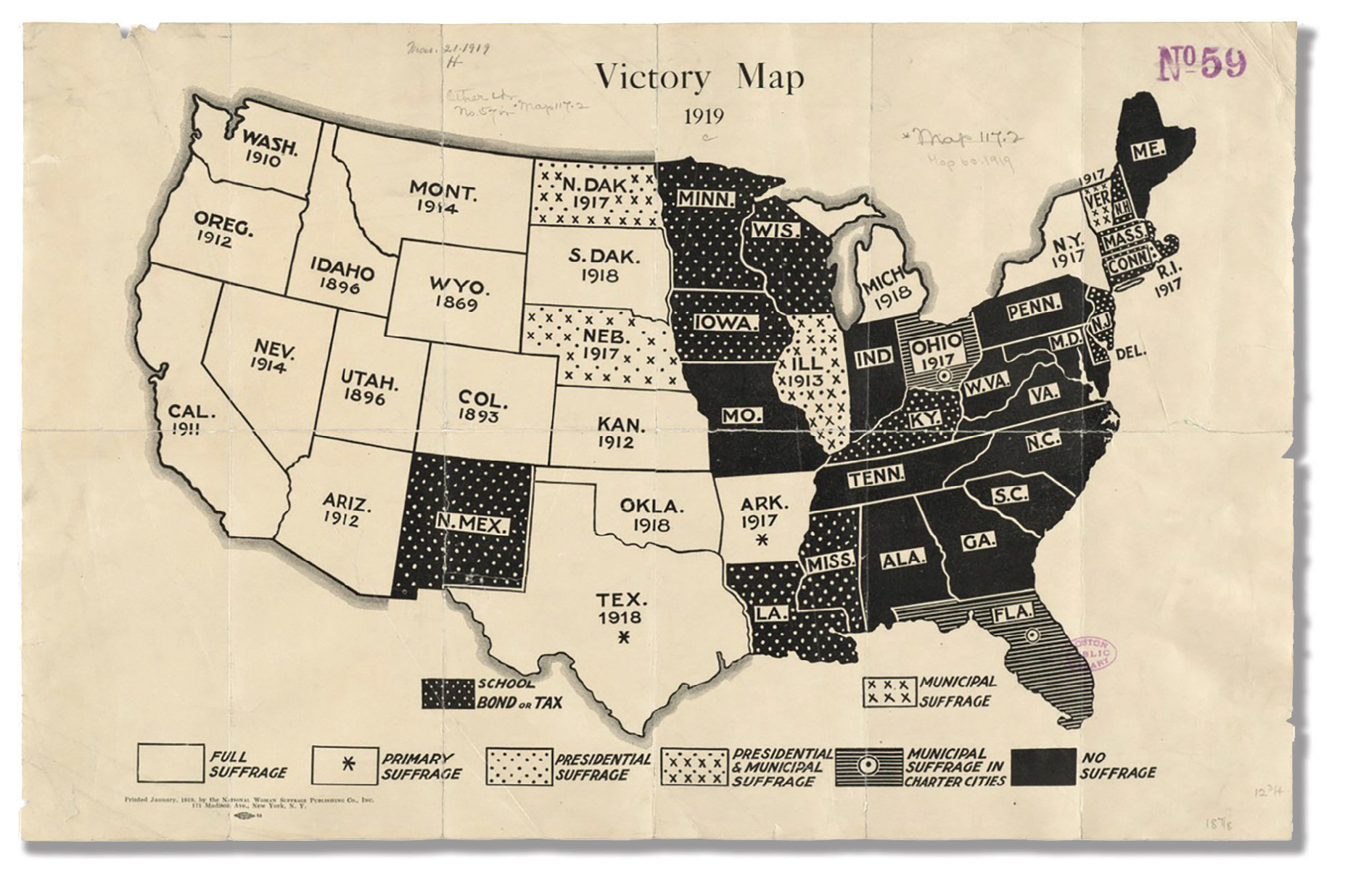

In 1869, Wyoming became the first state or territory to grant women the right to vote. A few other Western states followed, but the big influx of states came after 1910.

In 1919, Tennessee became the 37th (and first former Confederate state) to allow women to vote. So, by the summer of 1920, there wasn’t any question as to whether women in some states could vote; it was a question of whether women in all states could vote.

2 Delaware was expected to be the 36th state.

In the months following Congress’s approval of the woman suffrage amendment, activists from Carrie Catt’s National American Woman Suffrage Association and Alice Paul’s National Woman’s Party worked hard to get states to ratify it. They knew that states in the North and West were likely to approve the amendment. States of the former Confederacy were likely to reject it.

As expected, states such as Illinois, Wisconsin, New York and California rapidly approved the 19th Amendment. In March 1920, Washington became the 35th state to ratify it, and at that point, it looked like Delaware would put the amendment over the top. But in May 1920, Delaware rejected it. It was only because of this that Tennessee would have a chance in August 1920 to be the 36th state.

3 In August 1920, it wasn’t that hot.

Many stories about Tennessee’s passage of the 19th Amendment mention the heat. However, when the suffrage amendment passed in Nashville, it wasn’t that hot, at least not by today’s standards.

If you look at the recorded high temperatures for the month of August 1920, here they are: 81, 78, 84, 88, 88, 84, 84, 82, 78, 76, 76, 85, 83, 80, 82, 84, 86, 87, 85, 87, 70, 74, 76, 80, 83, 83, 82, 82 and 85.

As this detailed map shows, many states approved the right of woman suffrage before 1920. (Boston Public Library Map)

I don’t know about anyone else, but I wish these were the high temperatures for the month of August 2020!

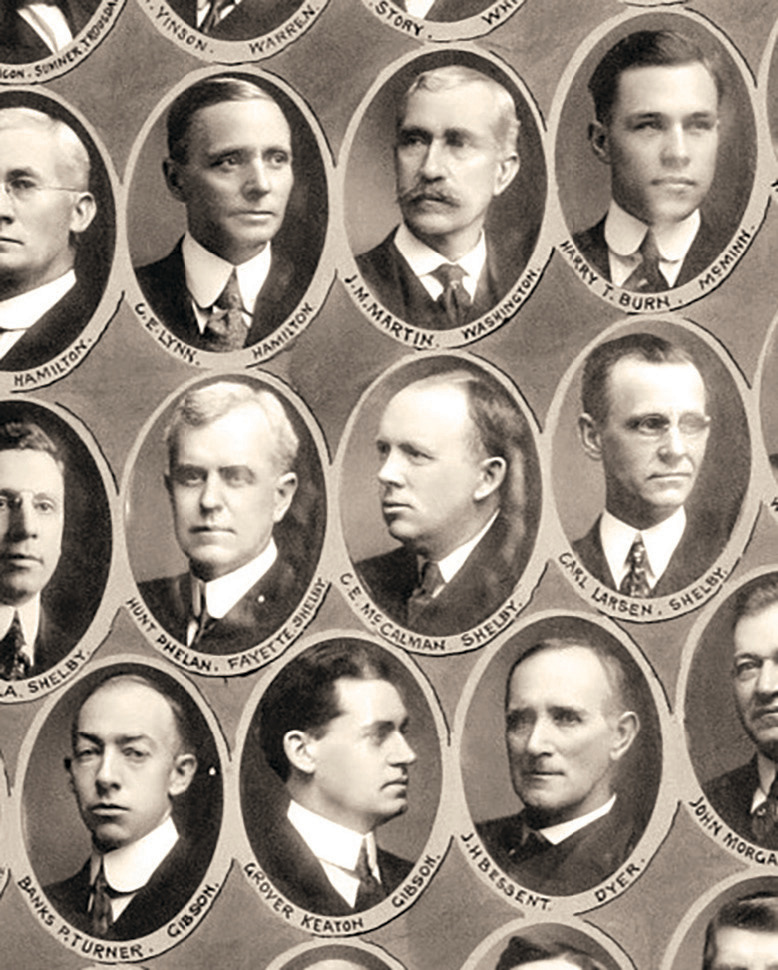

Over the years, Harry Burn of McMinn County (upper right) has received a huge amount of publicity for changing his vote on the suffrage amendment at the last minute. However, Banks Turner (lower left) has received almost none, even though he also changed his vote from a no to a yes on the last day. (Tennessee General Assembly photo)

4 The suffrage activists didn’t necessarily get along with each other.

There were two main pro-suffrage organizations in 1920 — the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA), led by Carrie Catt, and the more radical National Woman’s Party (NWP), led by Alice Paul. Although these organizations lobbied for the same cause, they used different methods.

In Tennessee, the NAWSA was led by Anne Dallas Dudley, prominent and wealthy Nashville socialite. Meanwhile, the radical Sue Shelton White was the most famous NWP leader from Tennessee. Suffice it to say that these women didn’t always have nice things to say about each other. “Their (NWP’s) banners should be called ‘banners of shame,’” Anne Dudley once said, calling radicals such as Sue Shelton White “half-crazed fanatics.”

5 Two of the most important industries that lobbied against the woman suffrage amendment were the liquor industry and the railroads.

Why the liquor industry? Because many of the women who lobbied for woman suffrage had lobbied for prohibition.

Why the railroads? Because many business leaders thought woman suffrage would be bad for business.

6 There were some prominent women lobbying against the amendment.

When you think about people voting against the suffrage amendment, it is tempting to visualize middle aged and older white men, smoking cigars and sipping whiskey in the Jack Daniel’s Suite at the Hermitage Hotel.

However, don’t forget that there was a group in full force on Capitol Hill called the Tennessee State Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage. Led by Josephine Pearson, it argued that woman suffrage would be bad for motherhood and the family, that it would hurt Southern white people at the expense of African Americans and that it was an idea imposed on Tennessee by “outsiders.”

7 Nashville voted against the amendment, and Memphis voted in favor of it.

On Aug. 19, 1920, there were six members of the Tennessee State House from Nashville. Five of the six voted against the amendment.

There were seven members of the Tennessee State House from Memphis, and all seven of them voted in favor of the amendment.

These facts make us realize that two people who had a lot to do with the amendment passing were State Rep. Joe Hanover of Memphis (who led the movement on the House floor in favor of the amendment) and E.H. Crump of Memphis, who had huge influence over the Shelby County delegation.

8 Harry Burn wasn’t the only state representative who changed his vote at the last minute.

The many stories about Harry Burn and the letter from his mother have obscured the fact that two House members changed their votes on the suffrage amendment on the last day. Banks Turner from the unincorporated Gibson County community of Nebo also changed his vote from no to yes. Had he not done that, the amendment would have failed.

When Turner died in 1953, his suffrage vote wasn’t even mentioned in his obituary!

9 The passage of the 19th Amendment didn’t result in the passage of the “next” amendment.

In the early 1920s, many people assumed that the passage of the 19th Amendment would lead to the passage of an amendment that would authorize Congress to regulate the “labor of persons under eighteen years of age” — the so-called “Child Labor Amendment.” After all, many of the people who lobbied for and supported woman suffrage were also against the use of child labor in factories, which was still a common practice in those days.

However, the Child Labor Amendment was rejected by the Tennessee General Assembly in 1925, approved by only 28 of the 48 states, and never became part of the U.S. Constitution.

10 The phrase “Perfect 36” had a different meaning at the time.

(I need to credit my friend David Ewing for making me aware of this one.)

A lot of folks have used the phrase “Perfect 36” to describe Tennessee’s passage of the 19th Amendment. (I used it myself until I discovered what I’m about to tell you!) However, in 1920, the phrase had a more politically incorrect meaning.

In 1918, a silent picture called “A Perfect 36” was released starring Mabel Normand. According to Wikipedia, “The plot involves Normand’s clothes being stolen in a mix-up while she was swimming, necessitating her spending most of the film running around naked trying to straighten everything out.”

When, in the early 1920s, male reporters referred to Tennessee as the “Perfect 36,” they were making a double entendre.