Vietnam Veterans recall their service and their return to civilian life as “Better Men.”

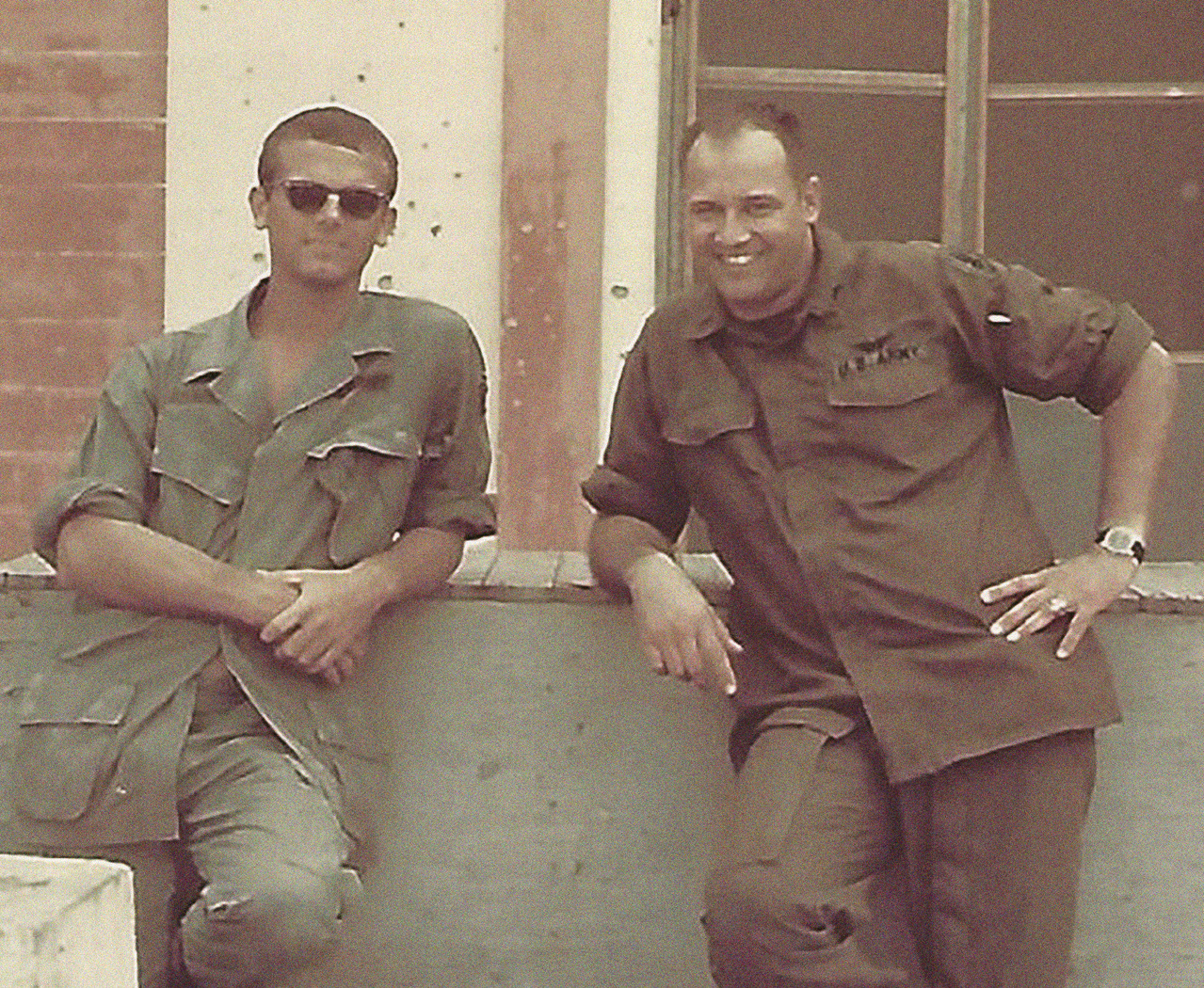

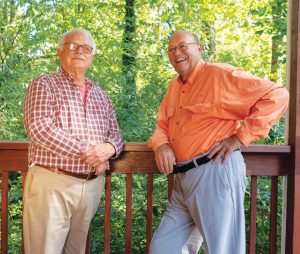

Buddy Mitchell, left, and Dave Stroud, right, recreate a photograph from their time in Vietnam. With the East Tennessee trees — and more than 50 years — behind them, they are a far cry from the commotion and concerns of combat.

Invisible soldiers are all around you: in line at the grocery store, sitting in meetings, sharing a church pew. They may even be in your home. These unseen soldiers give no indication they exist, although by being near you, they have almost certainly made your life better and your community stronger. They’re not ghosts: The soldiers who stand beside you unseen in your daily life are Vietnam veterans.

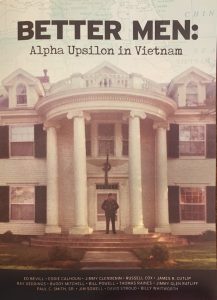

“Better Men: Alpha Upsilon in Vietnam” is a compilation of stories from 14 Vietnam veterans who, before they became brothers of war, were already brothers at the University of Tennessee at Martin’s Alpha Upsilon chapter of Alpha Gamma Rho (AGR), the national agriculture fraternity. The motto of AGR is “To Build a Better Man.” Twenty-one brothers from Alpha Upsilon served in Vietnam. All returned alive; 14 of the 17 remaining brothers participated in the “Better Men” project. In a number of cases, their recollections of Vietnam had never been spoken aloud.

Vietnam veterans went to war because they had to; the welcoming arms of their countrymen would have done much to heal warriors stretched to their limits physically and emotionally. “I didn’t know much about how the war was viewed back in the States,” said Russell Cox, an AGR from Crockett County featured in the book, recalling his thoughts while he was in Vietnam. “I didn’t know to what extent it was; I wasn’t really concerned. I was just trying to get up every day and make sure I made it back.”

Instead, they returned home to be accused of complicity in a controversial war. “I got spit on,” said Thomas Raines, another lifelong resident of Crockett County. “I will never forget that. I got spit on. I was still in uniform.”

“It more or less shut up all of us who went,” said Paul Smith, a Wilson County native who retired from a military career as a lieutenant colonel. “There are so many people you don’t know who served or what they did. No one has ever asked me about my time in Vietnam.” Veterans just locked away those years and got back to the business of living their lives. Today, with more than 50 years back on home soil, they still wait silently for a homecoming they never got.

So how is an invisible soldier persuaded to be seen at last, agreeing to difficult, hours-long interviews that would be committed to print?

Fraternity brothers told them that if they shared their stories, it might help someone else. They could share insights on how to keep going while actively living through a traumatic time. They could share what they wished everyone knew about Vietnam veterans. Trusting their fraternity brothers, they agreed to use their lives yet again in service for others.

The excess and privilege sometimes associated with fraternity life could not have been imagined by these naive farm boys. College students in the 1960s were born in the ’40s; much of rural Tennessee was not even electrified at that time. There were no togas at the AGR house, a dilapidated home the first brothers bought, repaired and maintained themselves. “We lived upstairs; there was no heat,” said AGR and former Mohawk pilot David Stroud, a Greenvale native. “We had bunk beds … it was a grand and glorious facility!” A house mother ensured that rules and social graces were enforced. AGRs were required to live there, and each new AGR was assigned an older study partner; they shared desk space and mandatory study hours.

“We were all poor as church mice,” said Stroud. “Most were working to survive. I worked in the cafeteria; Martin promised me a job — that’s why I ended up going there.”

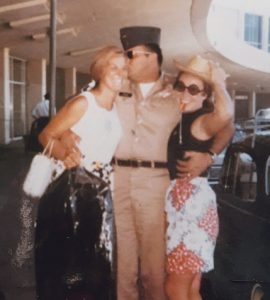

As a Mohawk pilot, Stroud was involved in some of the most dangerous missions of the Vietnam era — as well as risky pranks and adventures. One such incident recalled in “Better Men” included AWOL: Stroud flew off course to visit his best friend, Buddy Mitchell. Both were wounded in Vietnam.

Mitchell came home from Vietnam to a career with UT at Martin and in Knoxville. He ultimately served as interim chancellor for the UT Institute of Agriculture on three separate occasions. “The fraternity was just transformational in my life,” said Mitchell. “The AGR guys came over, and they invited me to this rush party,” said Mitchell. “I thought they said ‘rust party.’ I went around telling people I was invited to a rust party!

“They gave me leadership roles. They pushed me into things. ‘We need campus-wide leadership in our fraternity,’ they said; I was vice president of student government. I was a ‘Noble Ruler’— the best title I’ve ever had. Young men come together in packs and tribes … through history, that’s what we do. A pack can do enormous good or enormous bad. What better pack could you possibly have than a group that wants to build better men?

“Except for my parents, I consider that fraternity experience at Martin the most influential, positive experience of my life.”

Only 25 percent of Vietnam vets were drafted, giving the impression they were anxious to fight a foreign war. The truth is that young men chose not whether they would serve, but how. Depending on shifting draft and deferment regulations, a certain route might stave off service until a less dangerous point in the war, give a soldier his best chance of survival or help him learn skills leading to a postwar career.

Every American male who attended a public land grant university participated in mandatory ROTC (Reserve Officers’ Training Corps) — getting information and opportunities unavailable to those who did not attend college. “I knew I was going to Vietnam,” said AGR Ed Bevill, who now farms the same land near Cumberland City that his grandparents owned. Bevill ended up making a career in the military, earning the rank of colonel and serving as brigade commander. “I knew Vietnam veterans because of ROTC. Some of those instructors had already been to Vietnam as advisers; you had guys with first-hand experience you could talk to. Some guys got caught up in the draft and had to go. I was going as an officer.”

“The stories they were telling were strictly horror stories to a 19- or 20-year-old boy,” said Thomas Raines. “I knew that when I finished college, I’d be drafted; I decided that I’d much rather be an officer than an enlisted person.”

Thus, many men “avoided” the draft by “volunteering.” Unless draftees had specific skills, they were the ones most likely to be on the front lines in battle as foot soldiers. Fortunately, farm boys make good soldiers. They know how to shoot, how to operate heavy machinery, how to build fences and buildings. In short, even the AGRs who were drafted found they were valuable.

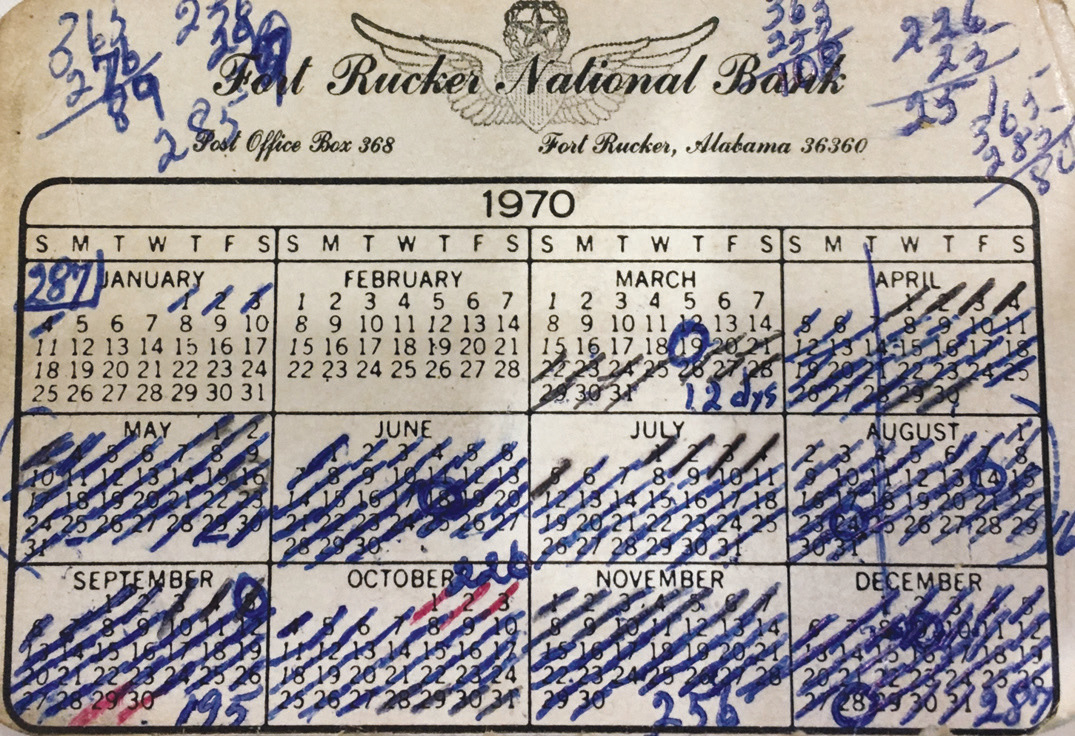

Jimmy Clendenin, farmer and lifelong resident of Clifty, was drafted the week he completed college classes. “I finished my coursework in March, but I hadn’t walked through the May graduation line.” Clendenin’s skill with heavy machinery was quickly spotted, and he spent most of his time in Vietnam operating bulldozers — pushing down jungles, sweeping for mines and building roads. “I probably had that little dozer stuck in a rice paddy on graduation day!” said Clendenin. “Yeah … about that time, I was right in rice paddy country.”

Jimmy Clendenin, farmer and lifelong resident of Clifty, was drafted the week he completed college classes. “I finished my coursework in March, but I hadn’t walked through the May graduation line.” Clendenin’s skill with heavy machinery was quickly spotted, and he spent most of his time in Vietnam operating bulldozers — pushing down jungles, sweeping for mines and building roads. “I probably had that little dozer stuck in a rice paddy on graduation day!” said Clendenin. “Yeah … about that time, I was right in rice paddy country.”

Jim Sowell, an Obion County native who is now an attorney in Dickson, decided to get drafted. “When I got out of college, I really became aware of the war; every time I interviewed for a job, they’d ask me what my draft status was. I’d have to tell them: 1A. They’d say, ‘We like you, but you get that taken care of first. Then come back and see us.’ I couldn’t get a job because of my draft status! I went up to the draft board and told them to draft me. I did not enlist; that was a three-year obligation. I told them to draft me … a two-year obligation.”

Some men had to choose between jail or “volunteering” for service. “There were quite a few guys who had the choice of coming there or going to jail!” said Billy Whitworth, who lives in Hickory Withe, where five generations of his family have lived. “Once you got to know those guys and their stories, they were just like I was. I had done some of the things these guys had done; they got caught, and I didn’t. You had guys in there, hippies with long hair, every kind you can think of, from every kind of background. We all went through that barbershop, and we all came out the other side … just alike. You had your green uniform on. That was it.

To read more about the veterans

“Better Men: Alpha Upsilon in Vietnam” is available now through The Tennessee Magazine Marketplace online store at tnmagazine.org/shop. Please allow four to six weeks delivery time.

“We were all one.”

There were those who used family influence to dodge the draft; others would flee the country. Deferring service too long or seeking some excuse to avoid Vietnam was not an option for better men, however. Whether the war was right or wrong was not a consideration; neither was how well the war was or wasn’t being fought. To shirk the call of duty meant that another young man — just as loved by his family, just as full of potential, hopes and plans — would go to war instead.

“I knew I wasn’t any better than anybody else,” said Mitchell. “Instead of going to get my doctorate, I knew it was my turn. If the boy pumping gas back in McLemoresville had to go, I had to go. I wasn’t any better than him, so I went. I really did it for myself, in a way. I was forced to do it … but I wanted to do it because I wasn’t better than anybody else.

“A lot of Tennesseans go to war. We are the Volunteer State. We go.”

The veterans in “Better Men” humbly accepted their country’s requirement into dangerous service not as seasoned adults but as the youngest of men. That they would face anger and blame for a politically mangled war over which they had no control is difficult to fathom today. In the decades after Vietnam, each of these profiled veterans continued to demonstrate honor, hard and honest work, love of family and community and the courage it takes to lead an unselfish life in a time when professed values and actual behaviors seem seldom in sync.

The veterans in “Better Men” humbly accepted their country’s requirement into dangerous service not as seasoned adults but as the youngest of men. That they would face anger and blame for a politically mangled war over which they had no control is difficult to fathom today. In the decades after Vietnam, each of these profiled veterans continued to demonstrate honor, hard and honest work, love of family and community and the courage it takes to lead an unselfish life in a time when professed values and actual behaviors seem seldom in sync.

This is the ordinary heroism to which we all are called.

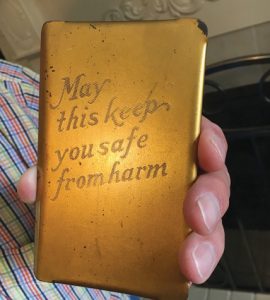

Springfield native and Alpha Upsilon brother Bill Powell lost a leg in Vietnam. Though his life path was forever changed and challenged by that loss, his narrative highlights a source of strength shared by all his brothers: deep faith and values. The veterans attest that both can serve as guides in any battle a person may face, whether waged in a foreign country or within one’s own life.

“I’ve always trusted that God will take care of me,” said Powell. “I know for a fact that without Him, I wouldn’t be here. He brought me through some tough times, a lot of times when it was just me and Him, nobody else.

“I’ve never felt abandoned. I’m not preaching to anyone; that’s just the way I feel. I’ve never, ever felt alone. I’ve known He’s always there. Even on an outpost in Vietnam, at night, when I’m the only one awake. I knew He was there. Still now, in situations today, you feel like you’re the only one … but you’re not.”