Now that the 100th anniversaries of World War I and the influenza epidemic have passed, I thought it might be fun to look back at newspapers from 100 years ago, focusing on the legislature. Here are some of the more interesting stories from the 62nd Tennessee General Assembly, which met in the spring of 1921.

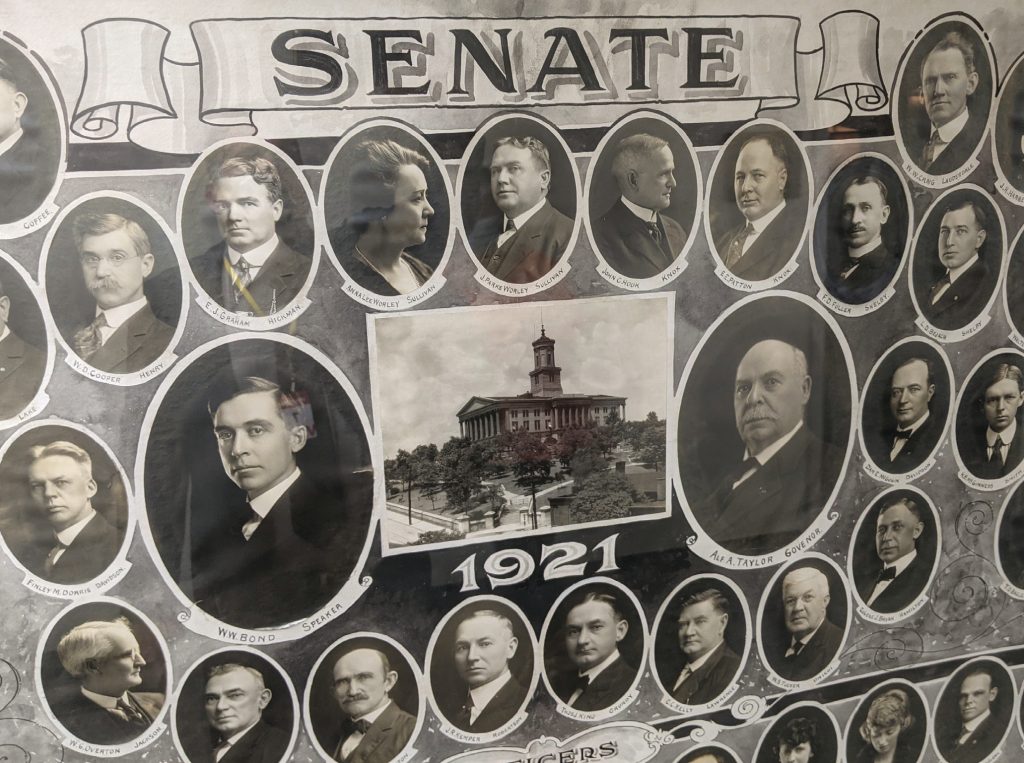

The Senate got its first female member. In a special election, Anna Lee Worley of Sullivan County was elected to replace her husband, the late Sen. Parks Worley, who died in early January. What made Anna Worley’s election to the Senate most ironic is the fact that Parks Worley had voted against the suffrage amendment five months before his death. During her first (and only) term in the state Senate, Sen. Anna Lee Worley sponsored at least one important bill that did pass. Senate Bill 737 made it clear that women were eligible to hold any elected office in Tennessee.

The most controversial and time-consuming piece of legislation the Tennessee General Assembly took up was a proposal to rewrite Nashville’s charter. What the 39-page bill did at various stages of the session (it was amended many times) is beyond the interest of people 100 years later. But I was amused by two aspects of the debate. For one, the measure was sponsored by state Sen. Dan McGugin, who was also an attorney and the Vanderbilt football coach. For another, the arguments about his charter bill got so ugly that, on Feb. 9, at his behest, a Tennessean reporter was kicked out of a committee meeting at which the bill was being discussed. I say this because in 1997, another Tennessean reporter (namely, me) was kicked out of a meeting at the General Assembly because the meeting was determined to be “secret.” (At the time, I didn’t realize I was taking part in a tradition!)

A proposal to provide free housing to teachers as a way of dealing with Tennessee’s teacher shortage was rejected by the state Senate. In arguing for the measure, Sen. E.E. Patton of Knoxville said there were more than 2,000 public schools in Tennessee that had not been able to operate the previous fall because no teachers could be found. “He characterized the teachers of the United States as ‘a great band of hoboes’ who travel from city to city and from town to town in the hunt for suitable places to settle down,” the Tennessean reported.

After considerable debate, a bill that would have mandated a program of physical training in public schools was voted down by the state House. The bill would have resulted in a program under which all students had physical exams (most people didn’t have access to a qualified doctor back then).

The General Assembly authorized $2 million in bonds to buy a block of land south of the Capitol and build an office building for state government (later to be named the War Memorial Building). This required the demolition of many stately mansions, including the mansion in which Gov. Alf Taylor was living at the time.

The General Assembly passed a few measures that affected the state’s historical landscape. It allocated $15,000 to purchase what was left of Andrew Johnson’s tailor shop in Greeneville — the first step toward the eventual creation of the Andrew Johnson National Monument. It devoted $2,000 to create a David Crockett monument in Lawrenceburg. It voted to make the birthday of Nathan Bedford Forrest (July 13) a state holiday, although the bill wrongfully stated that Forrest had been born “near” Memphis (he was actually born in present-day Marshall County).

The need for better roads was a recurring matter of discussion. Many House representatives and senators approached the governor about proposals to help fund a respectable highway system. However, Taylor seemed uninterested in raising taxes to build roads. The governor went as far as to suggest that the state use volunteers to build Highway 70 — implying that if everyone pitched in, the highway could be built in a weekend. “Uncle Alf — when he finds surcease from his fox-hunting engagements — is going to pull off his coat, grab a spade and help build a state highway in a day,” the Tennessean ridiculed.

The Tennessee legislature contemplated but rejected a “blue law” that would have given Tennessee the strictest Sunday restrictions in America. The proposal, known as the Cooper bill, did “not prevent anyone from going to church or Sunday school or getting a deep breath, but it does intend to stop every public service corporation — railroads, telegraph, telephone, newspapers, not to mention amusements,” claimed the Jan. 28, 1921, Union City Commercial Courier. “It is intended to prevent transportation of any kind, so that if anyone is taken suddenly ill, nothing whatever can be done towards getting physicians but to hoof it to the doctor and no medicine at all can be bought.”

In any case, it is just as well that the 62nd General Assembly voted down the Cooper bill. You see, it was the intention of both the House and Senate to finish their work on its 75th day of the session — Saturday, April 10, 1921. But as is often the case, arguments about this and that dragged on, and the session went on into the evening and even past midnight — which meant that the General Assembly was (technically) in violation of the Tennessee Constitution.

At midnight, the sergeants at arms of both chambers stopped the clocks, and the House and Senate continued for several more hours. So the same General Assembly that had contemplated passing a law that wouldn’t let anyone else work on a Sunday worked on a Sunday.