Tennessee has many ghost towns — abandoned because they were once owned by a coal company, because the railroad replaced the flatboat or because early routes were replaced with later ones.

This column focuses on towns permanently flooded by lakes created by the Tennessee Valley Authority and U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.

Before we do, I need to put the flooding of these communities in context. We should remember these places and be mindful of how much manmade dams and lakes changed our landscape. However, the creation of dams up and down the Tennessee and Cumberland rivers greatly reduced flooding and provided a lot of inexpensive electricity. I’m mindful of this as I type this column onto my internet-connected laptop, my air conditioner cooling the room.

East Tennessee

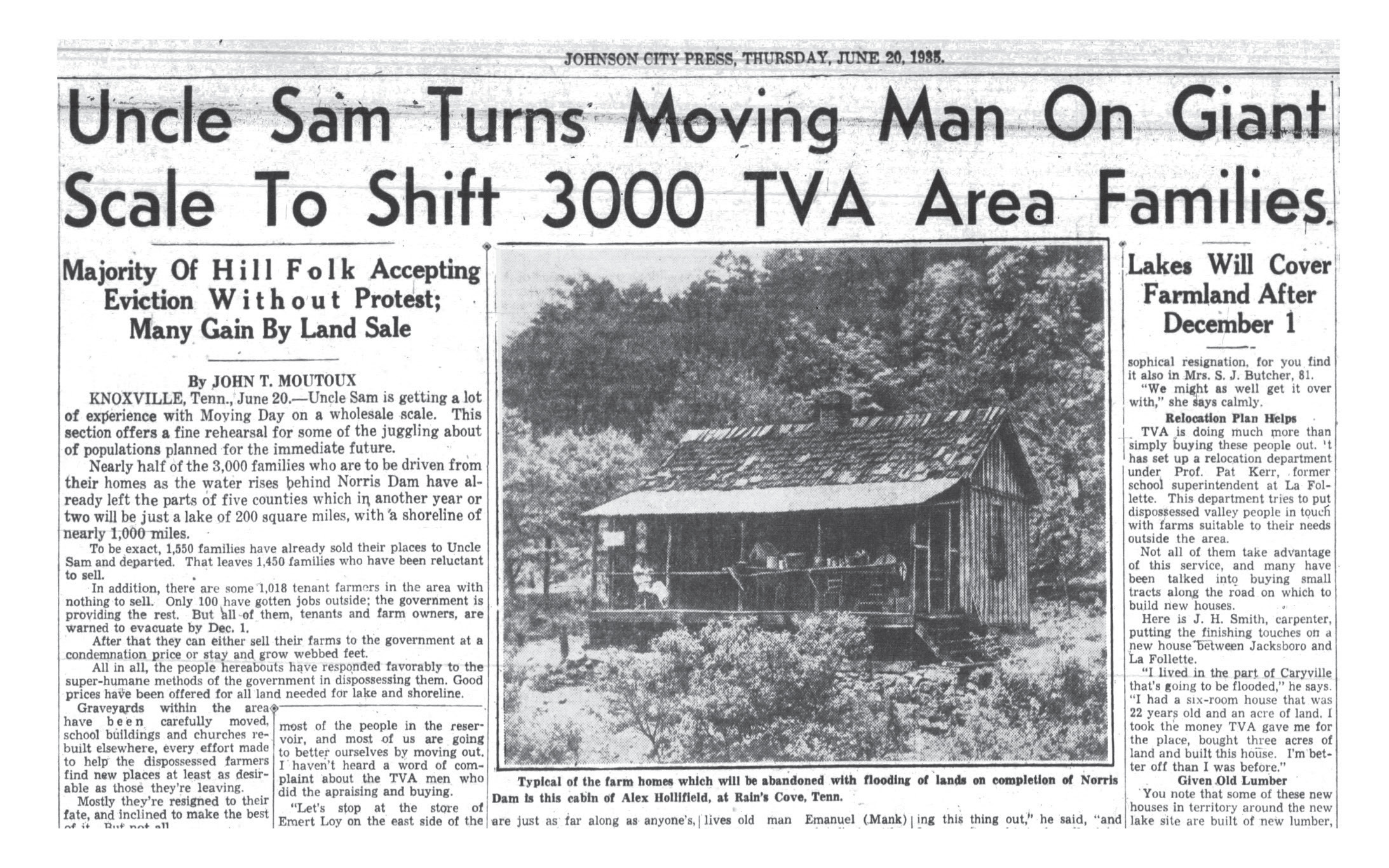

Big Barren, a small town along the Clinch River in Claiborne County, became famous in 1916 because of a flood that killed 25 people there. When Norris Dam was created in the 1930s, Big Barren was permanently flooded by the waters of Norris Lake. Most of the graves in the town were moved to a new cemetery in Union County now known as Big Barren Cemetery.

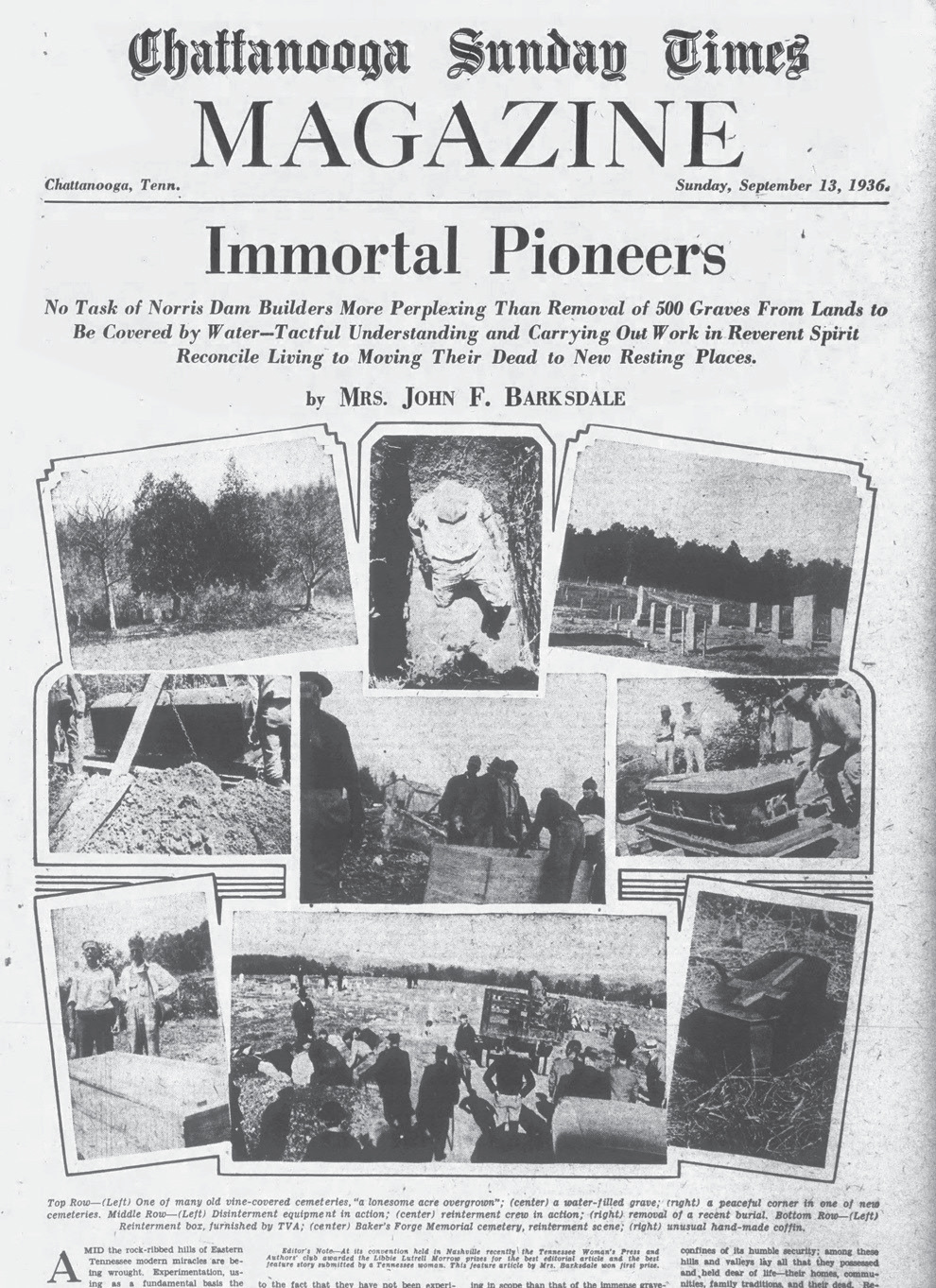

Near Big Barren was the Campbell County community of Baker’s Forge. I’m not sure what Baker’s Forge consisted of by the time Norris Dam permanently submerged it, but I do know that about 2,000 graves there had to be moved to what is now known as Baker’s Forge Memorial Cemetery. About 10 of those graves were Revolutionary War veterans, which makes me wonder what was left of them by the 1930s.

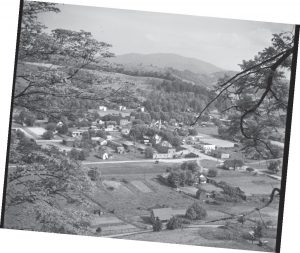

Loyston, just downstream from Baker’s Forge, was one of the better-documented permanently flooded towns in Tennessee history. Lewis Wickes Hine visited the Clinch River town in 1933 and took photos of the place before it was inundated by the waters of TVA’s Norris Lake. “Loyston has been in existence for more than 100 years,” a story in the Knoxville News-Sentinel reported at that time. “The town contains a mill, two stores, two churches, a post office, a grammar school and a high school. But this is not all there is to Loyston. There are old stories and traditions, familiar old tales that cannot be put down in statistics nor relayed in figures.”

Butler’s residents saved many artifacts before the flooding such as a horse-drawn hearse, now displayed in the town’s museum.

The Johnson County town of Butler had to be moved in the 1940s because of the creation of Watauga Lake. When it was relocated, some of the town’s residents saved many artifacts before they were discarded such as a horse-drawn hearse, the interior of the post office and equipment from the old lumber mill. Today, these objects are displayed in a wonderful museum in “New” Butler, which I highly recommend.

In Grainger County, Cherokee Dam on the Holston River permanently flooded the community of May Spring in 1942. Not a lot of people lived there, but it was known because of the old May Spring Farm and Mill. “Some of East Tennessee’s best flour was ground at the mill,” the October 12, 1941, Knoxville News-Sentinel reported.

Cherokee Lake also inundated Noeton, which required the Noeton Baptist Church to be moved and its cemetery exhumed.

The most famous structure permanently flooded by Cherokee Lake was the tavern at Bean Station — an inn built in 1814 along the first road connecting Knoxville to Washington, D.C. Just about every important person from early Tennessee history spent the night at Bean Station at one time or another. In fact, there was so much sentimentality about the old tavern that its stones, bricks and logs were stockpiled by TVA in case anyone ever wanted to rebuild it. (However, no one seems to know what happened to those stones, bricks and logs.)

Since it was a logical place to cross the Little Tennessee River, the Loudon County town of Morganton was a key locale during the Civil War. It also had a ferry crossing that remained active until the 1960s. However, Morganton only had about 20 buildings left when TVA bought the land in advance of the creation of Tellico Lake in the late 1970s. Today, flooded Morganton has that most-important digital-age status symbol: a Wikipedia page!

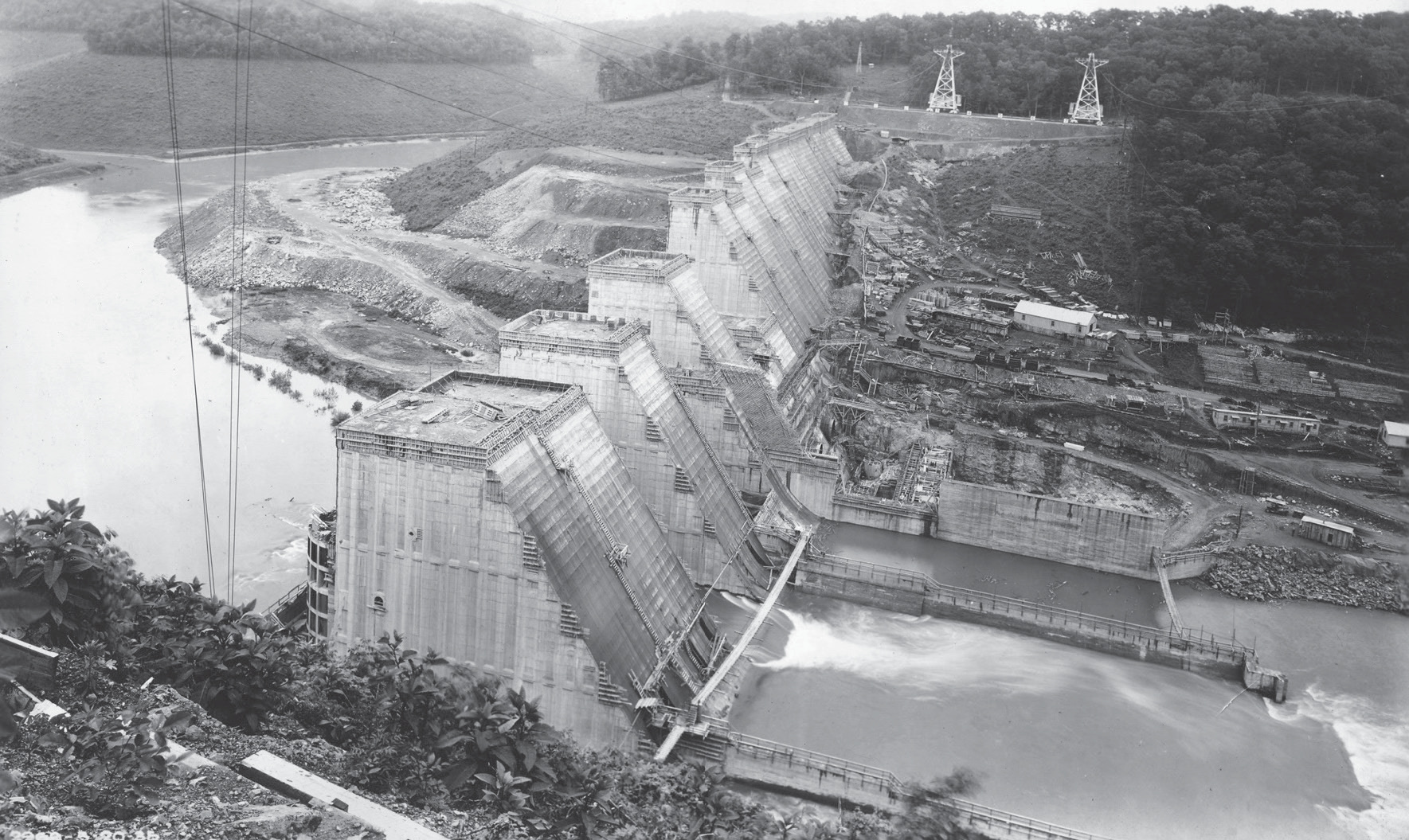

Norris Dam

Several small communities were flooded when Watts Bar Lake was created in the early 1940s. The best publicized was Rhea Springs, which once had a famous spring and hotel. “The hotel’s patrons came from Atlanta, New Or-leans, Memphis,” the Chattanooga Daily Times reported. “(It) was the largest and most popular watering place in East Tennessee.” Among other things, Rhea Springs had homes, cemeteries, an old academy building and a Methodist church built in 1840.

Downstream on the Tennessee River, about 2,000 families had to be relocated when Chickamauga Dam was built in the late 1930s. Parts of several Hamilton County communities were inundated — among them Bakewell, Soddy and Harrison.

Bakewell had an African-American community of about 40 families. Soddy had a hosiery mill, a gristmill, a gas station and many houses. Harrison had an elementary school, a church and several stores.

Harrison was also the county seat of Hamilton County from 1840 until 1870. So the place where early Chattanooga residents paid their taxes, where courts were held and chancery court officials sold enslaved people is now permanently beneath the waters of Chickamauga Lake.

Today, some of the land formerly occupied by Old Johnsonville sits in Johnsonville State Historic Park.

Before we leave East Tennessee, I need to mention a county seat that TVA spared. Dandridge, in Jefferson County, is named for America’s first, first lady — Martha Dandridge Washington. During World War II, the Tennessee Valley Authority built Douglas Dam on the French Broad River. It was a controversial project, first opposed by then U.S. Sen. Kenneth McKellar because of the amount of farmland it destroyed. But the people of Dandridge had their own reason for being concerned; under the original plans, Dandridge would be underwater.

The citizens of Dandridge made a direct appeal to First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, pointing out that this was the only place in the United States named for Martha Washington. Mrs. Roosevelt heard their appeal, spoke to her husband, and a levee was built protecting the town of Dandridge from flooding.

The ‘Other’ Tennessee River

Now we move downstream along the Tennessee River, through north Alabama, to where the Tennessee River borders Middle and West Tennessee. When Perry County was formed in 1819, Perryville was its county seat. Thousands of people who migrated to West Tennessee crossed the river at Perryville, and for a while, it was a bustling town. However, the part of Perry County on the west side of the river was later split off into Decatur County and its county seat placed at Linden. When TVA created Kentucky Lake in the 1940s, Perryville’s 250 residents had to be moved to higher ground, and a lot of old buildings were razed.

Continuing downriver was Johnsonville, a community made famous by a Civil War battle involving Nathan Bedford Forrest. When Kentucky Lake was created, about 350 residents had to be moved. TVA later built a power plant nearby, and the place became known as New Johnsonville. Today, some of the land formerly occupied by Old Johnsonville sits in Johnsonville State Historic park

Across the river from Johnsonville was Eva, a Benton County community similar in size to Johnsonville. In 1925, Gen. Mason Patrick, head of the U.S. Army Air Corps, was forced to land his airplane in Eva on a cross-country trip. “He got the best hot biscuits at Eva,” the Nashville Tennessean reported. Eva, its 400 residents and its biscuits had to move to higher ground when Kentucky Lake flooded the area.

Moving downstream and farther north, today you will find a huge grain elevator that still rises from the waters of Kentucky Lake. That grain elevator is all that is left of Danville, which contained homes, stores, a doctor’s office and a saloon. Danville was permanently flooded by Kentucky Lake, but, for reasons that remain a mystery to this day, the grain elevator was left standing.

When the Civil War began, the Confederate government built a fort on the Tennessee River in Stewart County called Fort Henry. The site was poorly chosen — in fact, it was flooded when the U.S. Navy successfully attacked it in February 1862. In the 1940s, Kentucky Lake flooded what was left of the fort and the small community near it. As buildings were being moved to make way for the lake, people were showing up and hauling off what was left of Fort Henry. A Nashville Boy Scout troop carried off logs from the old fort and used them to build a play fort at a small farm in Williamson County. A few months ago, I tracked down some of these logs, which were used to build a lovely house along the Harpeth River. However, the nice lady who owns the house asked me not to publicize its location.

The cover story for the Sept. 13, 1936, issue of the Chattanooga Sunday Times chronicles the arduous task of removing and replacing nearby graves soon to be flooded.

Cumberland River

The Tennessee Valley Authority built all the dams on the Tennessee River, but the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers built all the dams on the Cumberland River such as Dale Hollow, Old Hickory and Percy Priest.

The Clay County community of Willow Grove was flooded by the Corps of Engineers when Dale Hollow Dam was built in 1942. Despite the fact that there was a Willow Grove High School, I wasn’t able to find many articles and photographs of Willow Grove. However, in his memoirs, longtime U.S. Secretary of State Cordell Hull claimed that his political career started in Willow Grove. Hull, then 14 years old, won a debate at the schoolhouse there, which (according to his memoirs) convinced his father that his son should be sent to the best school he could afford. In other words, the place that launched the career of the greatest secretary of state in U.S. history lies under the waters of Dale Hollow Lake.

Previously I pointed out that TVA originally intended to flood the Jefferson County seat of Dandridge but built a levee instead. A similar thing happened in the Benton County town of Big Sandy. Originally, Kentucky Lake was going to flood just about every building, road and grave there. But in November 1941, TVA announced that it was going to build a mile-long dyke along Sugar Creek there, which prevented Big Sandy from being flooded.

All of this brings us to the strangest case of all. Jefferson, a town located where Stones River breaks into two tributaries, was the original county seat of Rutherford County. By 1938, when a Tennessean reporter wrote a story about the place, there wasn’t much left. “Today a telephone pole marks the center of the old square, but there is no mark to indicate the territory around the lone pole which once was a husting trading and swapping ground in a buoyant town that grew in the forks of Stones River.”

In the 1950s, when the creation of a Corps of Engineers lake in Davidson and Rutherford counties was announced, engineers said that old Jefferson would be permanently flooded. All that was left of Jefferson — and there wasn’t very much by that time — was burned, torn down and hauled away.

Alas, even engineers make mistakes. After the new reservoir filled up, the water didn’t extend quite as far as originally projected. The land previously occupied by the community of Jefferson remained high and dry.

Meanwhile, the lake they thought would flood Jefferson but didn’t was named for that very same reporter who had done an article about “Old Jefferson” back in 1938. You see, that Tennessean reporter met so many people as he wrote about obscure corners and abandoned communities in Tennessee that he eventually got elected to Congress.

His name was Percy Priest.

Telling ghost (town) stories

Do you have family histories or photographs relating to Tennessee towns claimed by the floodwaters? We’d love to check them out! Share your stories and photographs, and we’ll see if any organizations would like to archive them for their historical significance.