When I was growing up, I didn’t know what “indivisible” meant. I had to memorize it for a vocabulary test along the way, and it was then and only then that I learned that indivisible means “unable to be divided or separated.” But I never fully understood what “indivisible” meant, at least in terms of being an American, until I heard the story of World War II soldier Roddie Edmonds.

There was nothing extraordinary about Edmonds’ background. Born in Knoxville in 1919, he was the youngest of four sons of a professional wallpaper hanger named T.C. Edmonds. Roddie was a good student whose family attended Vestal United Methodist Church. He loved to play with other boys at Fort Dickerson, the abandoned Civil War fort near his home in South Knoxville. Rain or shine, Edmonds walked to school — a long walk by today’s standards.

“Every day Roddie would walk alone to high school with a hard biscuit — many days in his ROTC uniform — crossing the Southern railroad trestle over the Tennessee River,” one neighbor recalls in a new book about him written by his son, Chris Edmonds.

It goes without saying that Roddie Edmonds probably didn’t know many Jewish people growing up in Knoxville. That may not seem relevant, but it would eventually become important to his story.

In March 1941, Edmonds enlisted in the U.S. Army and was sent away for training to Fort Jackson, a U.S. Army base in South Carolina. A few months later, the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor, and the United States was drawn into World War II. Edmonds was sent to Europe, just like hundreds of thousands of other young men in his generation.

Fast forward three years. In December 1944, Edmonds was one of thousands of American soldiers taken prisoner during the Battle of the Bulge. Following a long forced march after being packed in boxcars for several days without food or water, they were separated into different prisoner of war camps for officers and enlisted men.

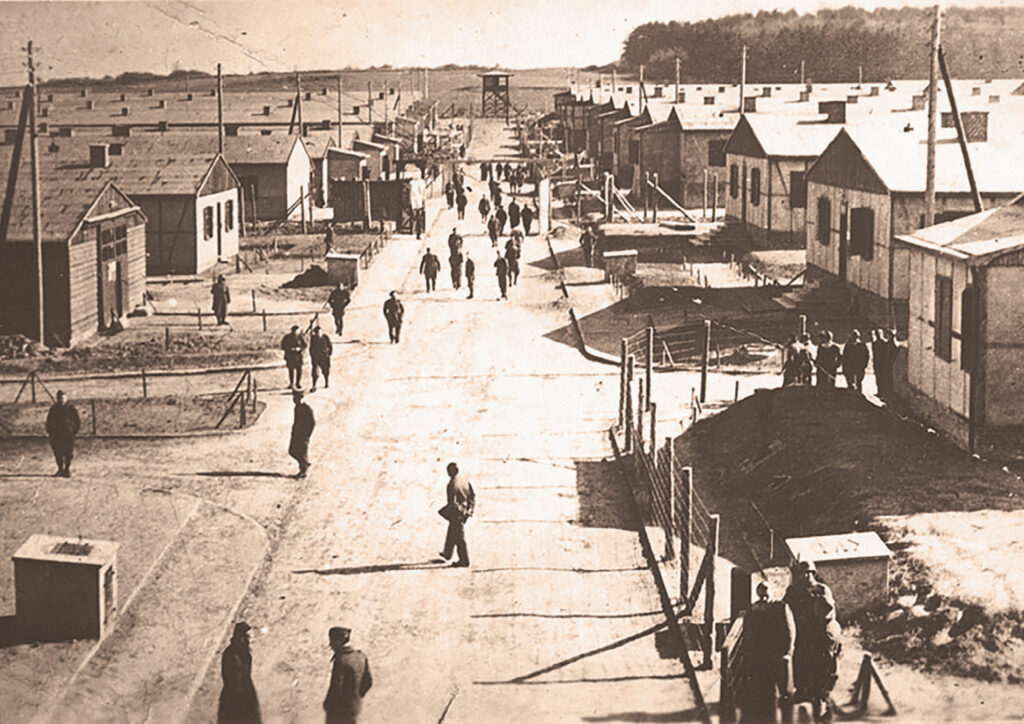

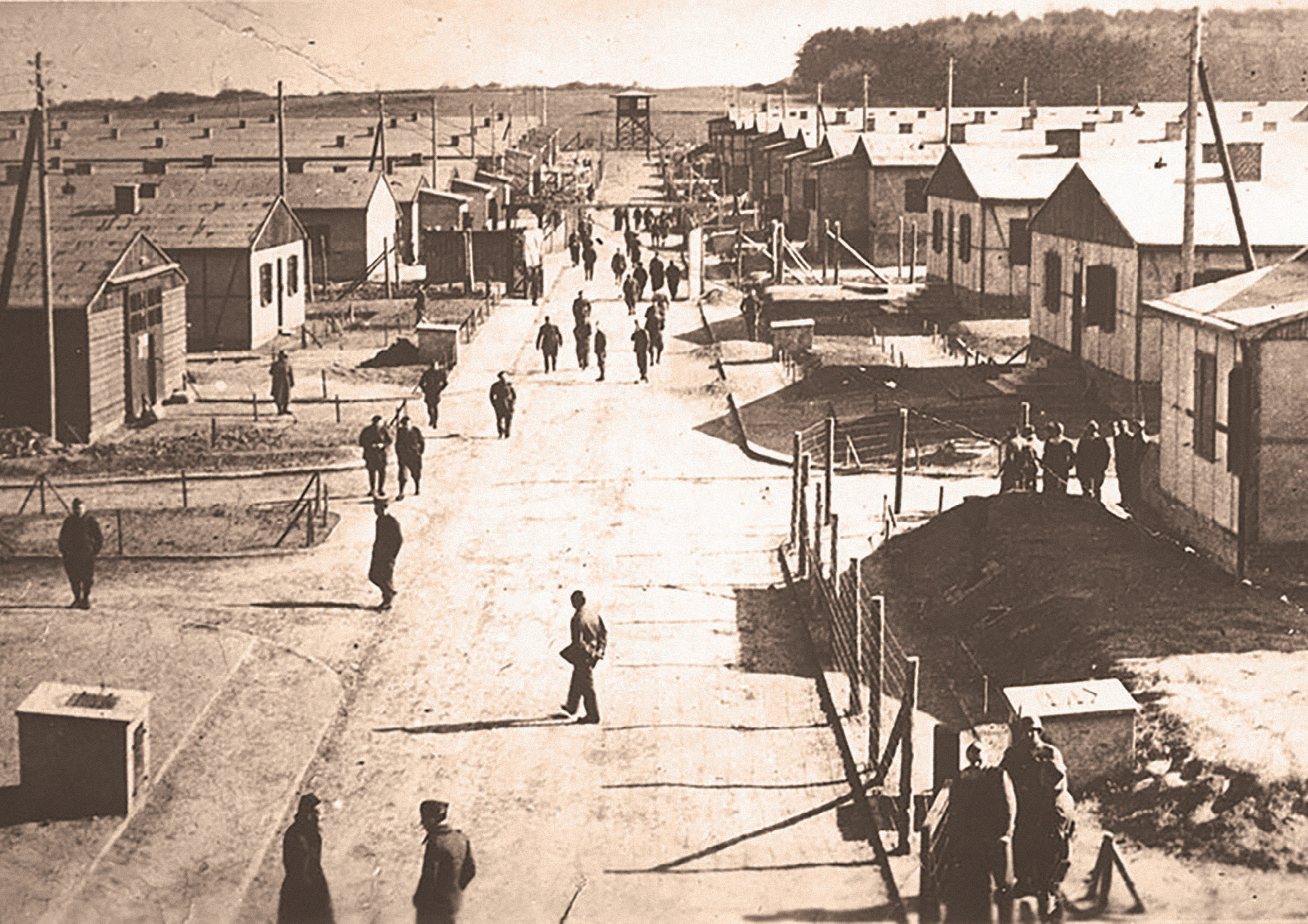

At the Stalag IXA enlisted POW camp near Ziegenhain, Germany, Master Sgt. Edmonds was the highest-ranking American. On one of the first nights in the camp, German prison guards told Edmonds that on the next day, they wanted all American prisoners of war who were Jewish to identify themselves.

Edmonds knew what this meant. He knew that the American soldiers who were Jewish would either be shot or sent to slave labor camps, from where they would probably never return.

Master Sgt. Edmonds sent out an order to his fellow Americans: The next day, when the Germans ordered all Jews to step forward, all American prisoners would step forward.

The next day, when the German commander ordered the Jews to “fall into formation,” all 1,292 American soldiers lined up.

“We are all Jews here,” Edmonds explained.

“They cannot all be Jews!” the German commander replied.

“We are all Jews!” Edmond said again.

The German commander took out a pistol and held it to Edmonds’ forehead, threatening to kill him if he did not order the Jews to be segregated. But Edmonds did not change his story.

“According to the Geneva Convention, we only have to give our name, rank and serial number,” he said, according to numerous eyewitnesses. “If you shoot me, you will have to shoot all of us, and after the war you will be tried for war crimes, and you will pay.”

The commandant gave up and stormed away.

We now believe that Edmonds’ actions and those of the 1,292 men who obeyed his orders saved the lives of about 200 American soldiers.

As incredible as this story is, what happened after Edmonds came home from the war seems even more remarkable to me. Edmonds never talked about this story and never received any official recognition for what he did during his lifetime. Only after he died in 1985 did his son, Rev. Chris Edmonds, first discover the story in his father’s diary. Rev. Edmonds researched it and heard confirming accounts of it from some of the Jewish prisoners of war whose lives he saved, such as New York native Paul Stern. “That critical confrontation occurred in a few short moments, yet it remained vivid in my mind these many years, and I blessed Sgt. Edmonds for his heroic act of courage,” Stern said.

“Roddie could no more have turned over any of his men to the Nazis than he could stop breathing,” said Lester Tanner, another Jewish soldier at the camp.

“Roddie could no more have turned over any of his men to the Nazis than he could stop breathing,” said Lester Tanner, another Jewish soldier at the camp.

“I’m so blessed to have learned his story,” Chris Edmonds said in a 2016 speech, “but more blessed to have met some of the men and the families he saved.”

Master Sgt. Roddie Edmonds eventually became the subject of news articles in national publications. Yad Vashem, the Israeli state Holocaust memorial in Jerusalem, added his name to a roll of honor called the “Righteous Among the Nations” because of his actions.

Last year, Edmonds wrote a book about his father’s World War II years called “No Surrender: A Father, a Son, and an Extraordinary Act of Heroism that Continues to Live on Today.” Last year, a historic marker about Roddie Edmonds was erected in downtown Knoxville.

A few months ago, I told the Roddie Edmonds story to a large group of Boy Scouts. To me, at least, his actions remind us that the word “indivisible” isn’t just a little-used vocabulary word. They remind us that, when America is at its best, it is cannot be divided.