This month is the 150th anniversary of the Battle of Franklin — also known as the bloodiest five hours in Tennessee history.

On Nov. 30, 1864, the Confederate Army of Tennessee charged into a well-entrenched Union force on the outskirts of Franklin in Williamson County. Wave after wave of men in gray uniforms charged, shoulder to shoulder, straight into musket, rifle and cannon fire. Some of them made it close enough to fire back and engage their enemy in hand-to-hand combat. Some of them even broke through for a brief time but were ultimately repulsed.

When it was over, about 7,000 of the 20,000 Confederates had been killed or were missing or wounded — a casualty count shocking even by Civil War standards.

Most of the battlefield of Franklin has long since been resold, dug up and turned into roads or sites for new houses, stores and office buildings. But you can still visit two different houses that were standing during the battle. One is called the Carter House, the other Carnton Plantation. In and around each home you can still see signs of this battle and its bloody aftermath.

First, the background of each structure:

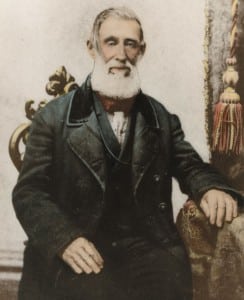

Randal McGavock was Nashville’s 11th mayor; today there is a high school in Davidson County named for him. In 1826, McGavock moved to Williamson County, intending to make money from farming. He named his plantation “Carnton” after his family’s ancestral home in Ireland and built a house that was a mansion by standards of the time. Among the guests entertained here was none other than Andrew Jackson, a friend from McGavock’s days in Nashville.

Randal McGavock died in 1843. By 1860, the plantation was owned by his son, John, and John’s wife, Carrie.

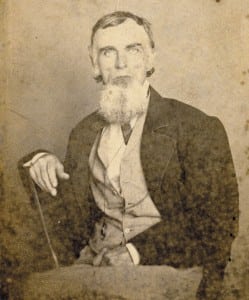

In 1830, a man named Fountain Branch Carter built a home about a mile west of Carnton Plantation. Carter was a prosperous man who made money as a farmer, merchant, surveyor and operator of a cotton gin. Over the years, he and his wife, Mary, had 12 children — eight of whom lived to adulthood. Three of their sons joined the Confederate Army when war broke out.

Now, we need to talk about the events of the Civil War in a larger context. During 1862 and 1863, the Union Army successfully fought its way through Tennessee, starting with forts Henry and Donelson, then through Nashville and Murfreesboro and southeast through Chattanooga. In the fall of 1864, the Confederate Army tried to defend Atlanta but, after a siege, evacuated the city.

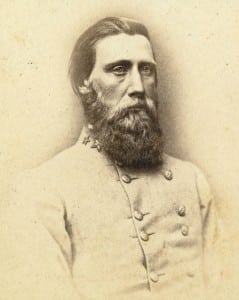

It was then that Confederate Gen. John Bell Hood came up with a different strategy. Instead of continuing to engage the advancing Union Army, he decided to take his army out of Georgia and attack Nashville in an attempt to cut off the Federal Army from its supply lines. After pulling out of Atlanta, the Confederates did just that — heading west into Alabama and then north into Middle Tennessee.

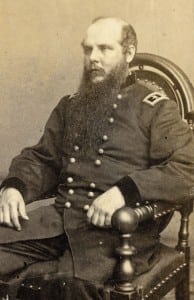

The bulk of the Union Army under William T. Sherman continued southeast from Atlanta on its now-legendary “March to the Sea.” But a Union force under Gen. John B. Schofield (who had been a West Point classmate of Hood’s) followed the Confederate Army on its move, mainly to protect the Union lines of supply.

On Nov. 29, Schofield’s men slipped out of Spring Hill, retreated to Franklin and, with the Harpeth River at their backs, dug entrenchments.

On the afternoon of Nov. 30, Hood ordered his men to attack. Several of his subordinate generals (one of whom was Nathan Bedford Forrest) tried to talk him out of it, convinced that a direct assault would be a disaster. They were unable to do so.

At about 4 p.m., Confederate soldiers loaded their weapons, said one final prayer, lined up and charged across the open fields of Williamson County. Many of them were shot down before they even got close to the Union entrenchments and guns. The noise was deafening. The air filled with smoke, and soon the ground was covered with dead and wounded soldiers.

The Confederates made as many as 18 separate charges, but at most parts of the line, the attackers didn’t get very far. In the middle, a group of soldiers momentarily breached the line near the Carter House. But they were soon repulsed.

The battle lasted past dark. After the shooting ceased, Gen. Schofield ordered his army to retreat across the Harpeth River toward Nashville. There was no doubt as to which side won this battle. Confederate casualties numbered around 7,000; Union casualties were about a third of that.

“Never on this earth did men fight against such terrible odds,” Sam Watkins, a private in the Confederate Army who fought at Franklin, later wrote in his memoirs. “It seemed that the very elements of heaven and earth were in one mighty uproar. Forward, men! And the blood spurts in a perfect jet from the dead and wounded.

“The earth is red with blood. It runs in streams, making little rivulets as it flows. Occasionally there was a little lull in the storm of battle, as the men were loading their guns, and for a few moments it seemed as if night tried to cover the scene with her mantle. The death-angel shrieks and laughs, and old Father Time is busy with his sickle, as he gathers in the last harvest of death, crying, ‘More, more, more!’”

While all of this was going on, residents of the Carnton Plantation and Carter House remained indoors, terrified of what was taking place. At the Carter House, 23 people (most of whom were children) remained in the cellar throughout the evening battle. They could hear everything from their safe haven, including soldiers trying desperately to beat their way into the house upstairs. After the battle ended, they came outside and, in the darkness, found hundreds of dead or dying men in the area immediately around the house.

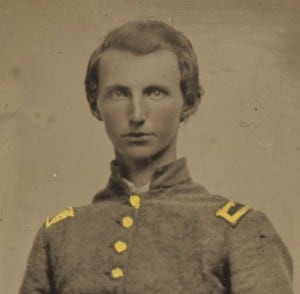

In an amazing coincidence, one of the casualties was Tod Carter, one of Fountain Branch Carter’s sons. Tod had survived two and half years of fighting in the Civil War only to be shot nine times in a battle that was fought near his own home. Tod’s family found him, injured on the battlefield, and brought him back to the very house in which he had been born 24 years earlier. He died two days later.

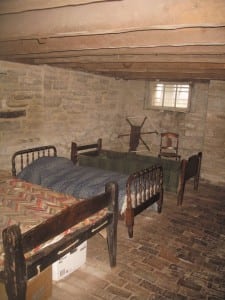

For the next several days, both the Carter House and Carnton Plantation were put into use as makeshift hospitals. We will never know how many men died in both houses during those awful days. There are, however, still bloodstains all over the hardwood floors of the Carnton Plantation that give you some reminder of what it might have been like.

The Carnton Plantation is also associated with this grim anecdote: No fewer than six Confederate generals died in the Battle of Franklin. At one time, the remains of four of them were lying side-by-side on the back porch of the Carnton Plantation.

So what became of all the dead bodies from the Battle of Franklin? During the days immediately following the battle, the surviving Confederate soldiers identified as many as they could. As many as possible were hastily buried in shallow graves marked with cedar headstones. (“Hastily” is the proper word here because the Confederate Army soon advanced toward Nashville and, only weeks later, was defeated again at the Battle of Nashville.)

After the war ended, the bodies of the Union soldiers were moved to Stone’s River National Cemetery in Murfreesboro. However, the federal government would not incur the expense of moving the Confederate dead, so the remains of the Confederate soldiers were moved to a two-acre plot of land donated by the McGavocks. For the rest of her life, Carrie McGavock kept watch over that cemetery and kept track of the identities of those buried in it. She eventually developed the nickname “Widow of the South.”

This fall is also the 150th anniversaries of the Battle of Johnsonville and the Battle of Nashville. For more about Johnsonville, go to www.tnhistoryforkids.org/places/johnsonville_forrest. For more on Nashville, visit www.tnhistoryforkids.org/insearchof/battle_of_nashville.

1 Comment

The photo at the top of the story of the cemetery is not of the Confederate Cemetery at the Carnton Plantation. The markers at that cemetery are small square stones, which were erected when the wooded markers deteriorated and are still there today.

Elizabeth