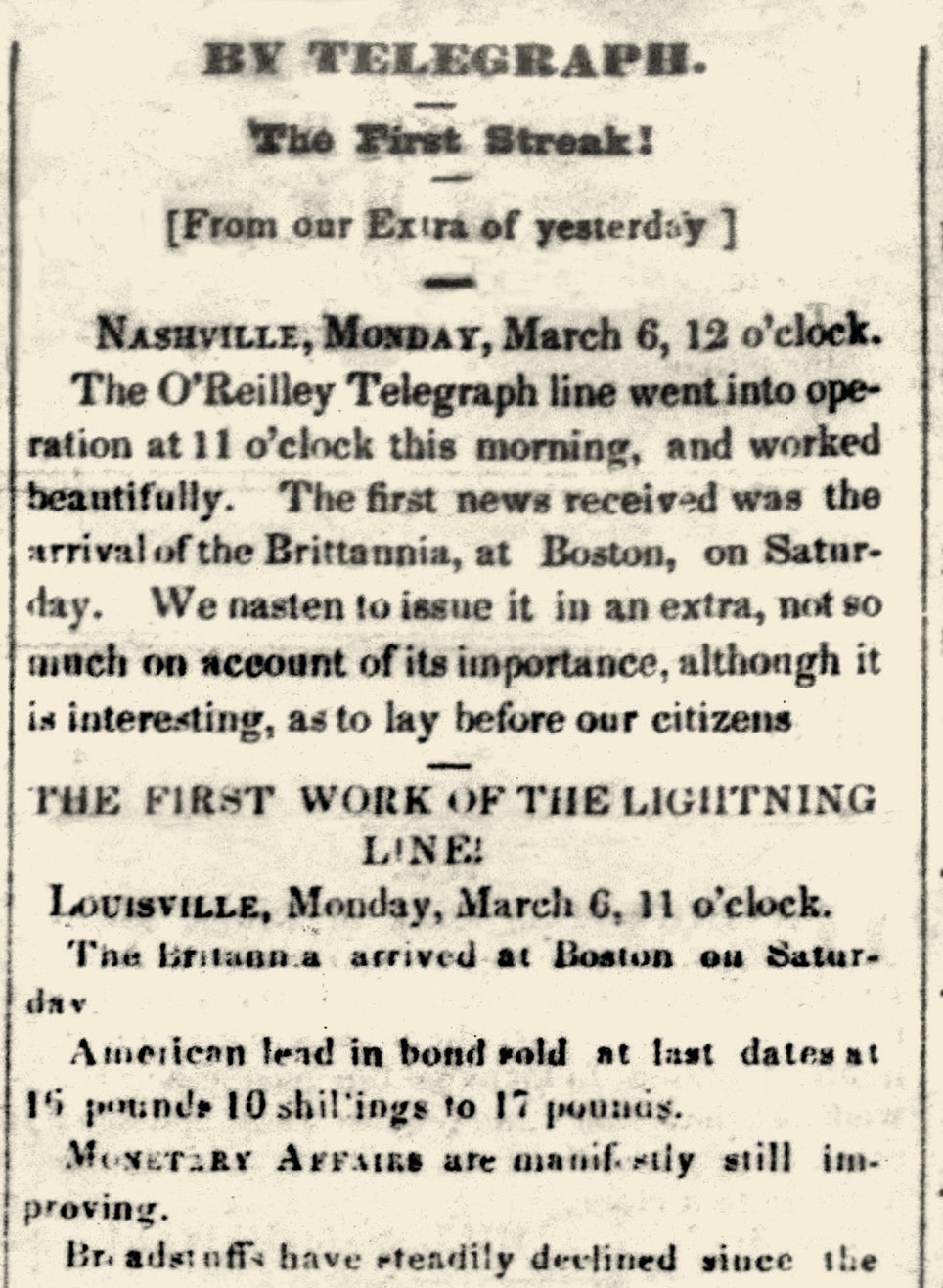

On Monday, March 6, 1848, people walked around Nashville, excitedly blurting out the same sentence. “Did you hear that the Brittainia arrived at Boston?” they said to each other.

It was a weird greeting. After all, no one in Tennessee probably cared about the steamship Brittainia. The important thing was that the Brittainia had arrived in Boston only two days earlier. The fact that the news was new is what made people so excited.

The news of the Brittainia was the first information ever transmitted to Nashville by telegraph — the first news ever received in Tennessee that had not come by foot, horse or boat. Before that day, it could take as long as three weeks for news to get from New York or Washington, D.C., to Nashville.

To understand the telegraph, you have to go back to another steamship voyage 16 years earlier. On a trip from Great Britain to New York in 1832, a painter named Samuel Morse and a doctor named Charles Thomas Jackson had several long talks about electricity.

People had known about electricity for years; Benjamin Franklin had conducted experiments with it 80 years earlier. But no one had found a way to use it. During their long talks, Morse and Jackson discussed the idea that if an electrical current could be created, then broken, then created and broken again and again in a series of patterns, it could be used for long-distance communication.

Morse was so excited when he got to New York that he started doing experiments with electricity. But he wasn’t the only man working on it. Other scientists were already trying to find on a way to use electricity to communicate over long distances, which is why we can’t really call Morse the “inventor” of the telegraph (it’s more complicated than that). What Morse eventually did with the help of Leonard Gale and Alfred Vail was come up with a series of circuits and relays that allowed the telegraph to send messages long distances.

On Jan. 6, 1838, Morse and Vail demonstrated their invention by sending a message along 2 miles of electric wire at the Speedwell Ironworks in Morris-town, New Jersey.

You might think that this demonstration would have gotten everyone’s attention, but it didn’t. A message sent along a 2-mile-long wire was one thing, but people still didn’t think you could send a message 20 or 30 miles. To demonstrate that, Morse needed a lot of money, which he didn’t have. He also needed help from the government.

You see, back then, you couldn’t just run 20 miles of wire from one place to another, unless you owned a 20-mile-long strip of land. But the federal government didn’t pay for or even allow this sort of thing in 1838. There was nothing in the Constitution about a person having the right to string telegraph lines all over the place, which is why members of Congress scratched their heads when Morse asked them to help him.

Finally, in 1843, the U.S. House of Representatives voted 89 to 80 to allocate $30,000 and give Morse the legal right to string a telegraph line a long distance. Morris and his friends got to work, laying a telegraph line along the way from Washington, D.C., to Baltimore. It wasn’t easy. After all, copper wires were hard to come by, and 38 miles of copper wire, well, didn’t exist. A company had to be hired to make the wire, long poles had to be purchased to hold the wire, and men had to be paid to stick the poles in the ground and string the wire to the top of them. This took time and patience, and Morse’s mood was up one minute, down the next. “He changes oftener than the wind,” Vail said. “Now he is elated up to the skies, then he is down in the mud.”

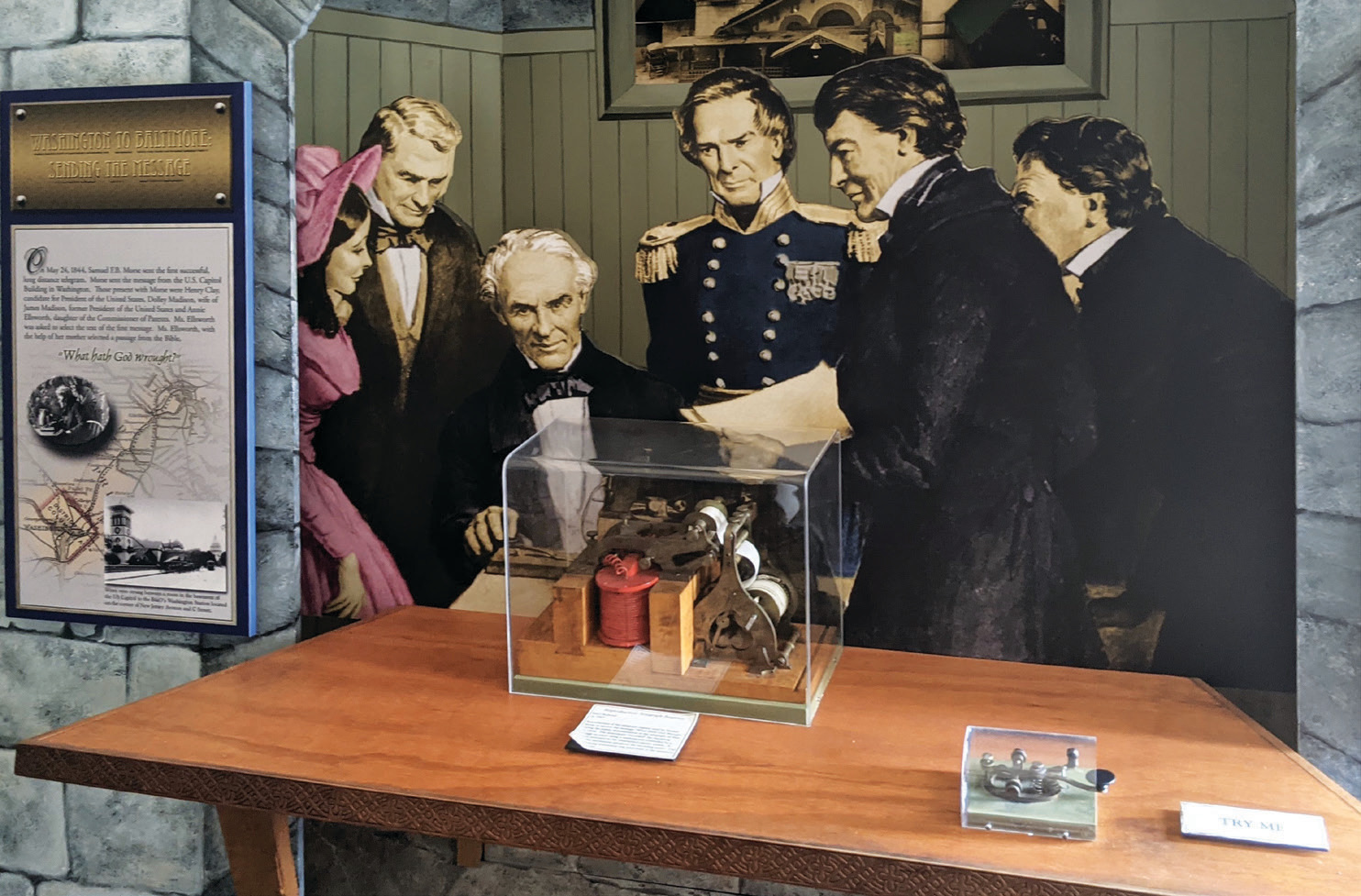

On May 25, 1844, a group of businessmen and elected officials gathered around a funny-looking electronic device in the Capitol building in Washington while another group of men gathered around another funny-looking electronic device at a railroad office in Baltimore. Morse, at one end, typed a series of dots and dashes into a machine that would have looked, to us, like a cross between a stapler and a small cash register. Vail, 40 miles away and on the other end the wire, translated the dots and dashes into a four-word message.

The dots and dashes came one at a time, and Vail translated them using the code that he and Morse had come up with. The first letter was “W.” The second was “H.” The third was “A.” And so on and so forth.

Vail transcribed the message one letter at a time. It spelled out the words, “What hath God wrought” — a Bible verse (Numbers 23:23) that a girl had chosen for Morse. The men standing around Vail at the railroad office in Baltimore were amazed. “Send him something in return!” they probably said. “No, no … send him a question! See if he can respond to a question.”

Newspaper reporters realized the implications of what Morse and Vail had done. “Time and space have been completely annihilated,” said the Baltimore Sun.

Morse now had the world’s attention and as many investors as he needed. He and his partners formed a business called the Magnetic Telegraph Company to build telegraph lines to New York City; Philadelphia; Boston; Buffalo, New York; and other large cities. Morse would also sign an agreement with a man named Henry O’Reilly, who started another business called the Atlantic & Ohio Telegraph Company. It was this company — the Atlantic & Ohio — that extended telegraph lines to Cincinnati, Ohio; Louisville, Kentucky; and Nashville.

The lines were installed at the rate of about 10 miles a day through Kentucky, heading south from Louisville. O’Reilly and his crew showed up in Nashville on or about Tuesday, Feb. 24, 1848, sticking poles in the ground and attaching wire to the top of them as fast as they could. It took a few days to get the apparatus working.

So on March 7, 1848, the Nashville Daily Union reported that the steamboat Brittainia had arrived in Boston — a bit of news that no one cared about but everyone talked about. Since that date, news has made its way instantly into Tennessee — via telegraph, later by telephone, later by television and later by internet.

Finally, a postscript about Morse and O’Reilly: By the time the telegraph arrived in Nashville, the partnership between the two men had become a rivalry and a lawsuit. That case (O’Reilly v. Morse) made it all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court.

In January 1854, the high court ruled in Morse’s favor, causing the collapse of O’Reilly’s business empire. When O’Reilly died in 1886, newspapers in Tennessee made a small mention of it, reporting that he had been a prominent citizen of Rochester, New York. But no one pointed out that it was O’Reilly who had brought the telegraph to Tennessee.