This month is the 50th anniversary of the opening of Opryland USA, a theme park that was an important part of Nashville’s tourism world until it closed in 1997. That being the case, I thought I’d write a column about why the park was created in the first place.

First, some Nashville business background:

Radio station WSM and the Grand Ole Opry were both created by Nashville’s National Life and Accident Insurance Company, which dates to 1901. After National Life merged with Third National Bank in 1968, National Life became known as NLT.

After the merger, NLT’s executives decided to move the Grand Ole Opry away from downtown Nashville and the Ryman Auditorium, where it had been performed since World War II.

Why?

Two reasons — one having to do with the venue, the other the neighborhood. Back then the Ryman had no dressing facilities, inadequate bathrooms, almost no parking and no air conditioning. “People were having heat prostration,” longtime NLT executive Walter Robinson Jr. once told me. “The actresses would say that it was the only theater in the country where your lipstick rolled down your lips, it was so hot in there.”

Meanwhile, the area around the Ryman had several businesses NLT executives thought were detrimental to country music’s image, not to mention theirs. Honky-tonks such as Tootsie’s Orchid Lounge were one thing. Gin shops, adult bookstores and hotels that rented by the hour were others. “People were getting shot across the street, and cars were getting broken into,” said E.W. “Bud” Wendell, an NLT executive who had once been manager of the Opry. “When all those people would stand in line around the block, every itinerant preacher, beggar, hooker and shoeshine boy was bothering them.”

The decision to move the Opry to the suburbs led to a discussion about how to draw people to it.

When I researched my book “Fortunes Fiddles and Fried Chicken: A Nashville Business History,” I learned that several people claimed that starting Opryland USA was their idea. WSM president Irving Waugh said it was based on something he saw on a visit to Houston. “When I saw what they had done around the Astrodome with a ride-oriented park and hotels, it made me wonder,” Waugh told me in 1999. “In Houston, the Astrodome was the centerpiece to that theme park. In Anaheim, the castle was the centerpiece to Disneyland. And in Nashville, the Opry House was going to be our centerpiece.”

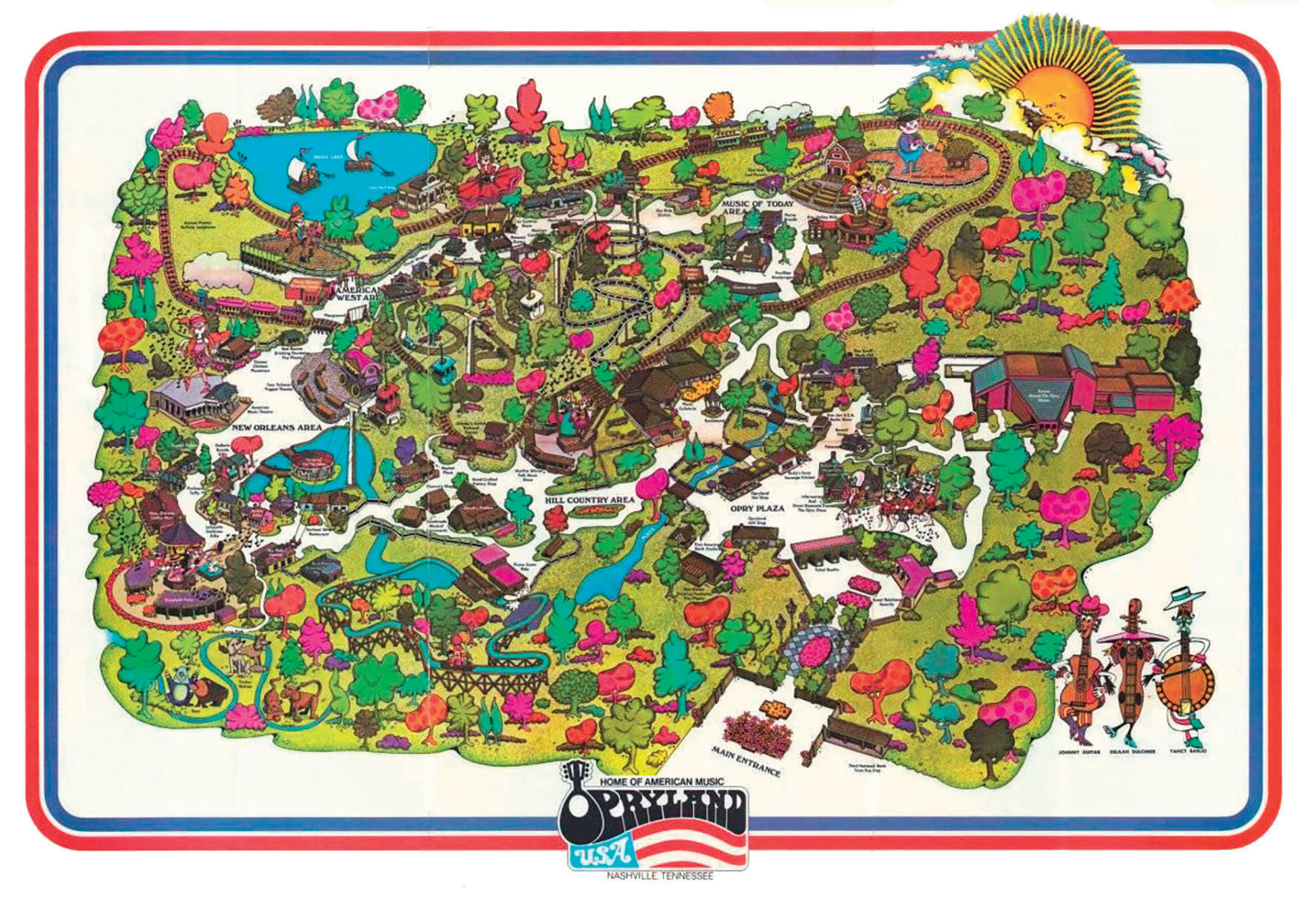

Under Waugh’s plan, Opryland would be organized on the different types of music that had influenced country music. Part of the park would have jazz music. Another part would have sort of an Appalachian feel and feature bluegrass. The park would also have some rides, even though there wouldn’t be as many as other amusement parks. “I wanted the park to have a certain number of rides, but I wanted a mix rather than a ride-oriented park,” Waugh said. With the Opry House and a theme park going in, it made sense to also put a hotel on the site.

In September 1969, NLT announced it would build the Opryland USA theme park, a new Grand Ole Opry House and a 150-room hotel called the Oprytowne Inn. About a month later the company chose a 400-acre site in the eastern part of Davidson County for its complex. The property was adjacent to a four-lane divided highway then under construction that was later christened Briley Parkway.

The theme park opened in the summer of 1972. Admission cost $5.25 for adults and $3.50 for children. The park exceeded even the most optimistic predictions; nearly 1.5 million people attended the park in 1972.

NLT delayed the construction of its hotel because of the gas shortage of the early 1970s. By the time the company was ready to move ahead with it, NLT had hired an executive with the Century Plaza Hotel in Los Angeles named Jack Vaughn to run the Oprytowne Inn. Vaughn and marketing director Mike Dimond convinced Bud Wendell to turn the small inn into a convention hotel. “They convinced me that the convention business is more stable and more profitable than the motel business,” Wendell said. By the time it broke ground, the Opryland Hotel and Convention Center was to have 600 rooms. It, too, exceeded projections; the hotel would expand many times over the years and now has an incredible 2,888 rooms.

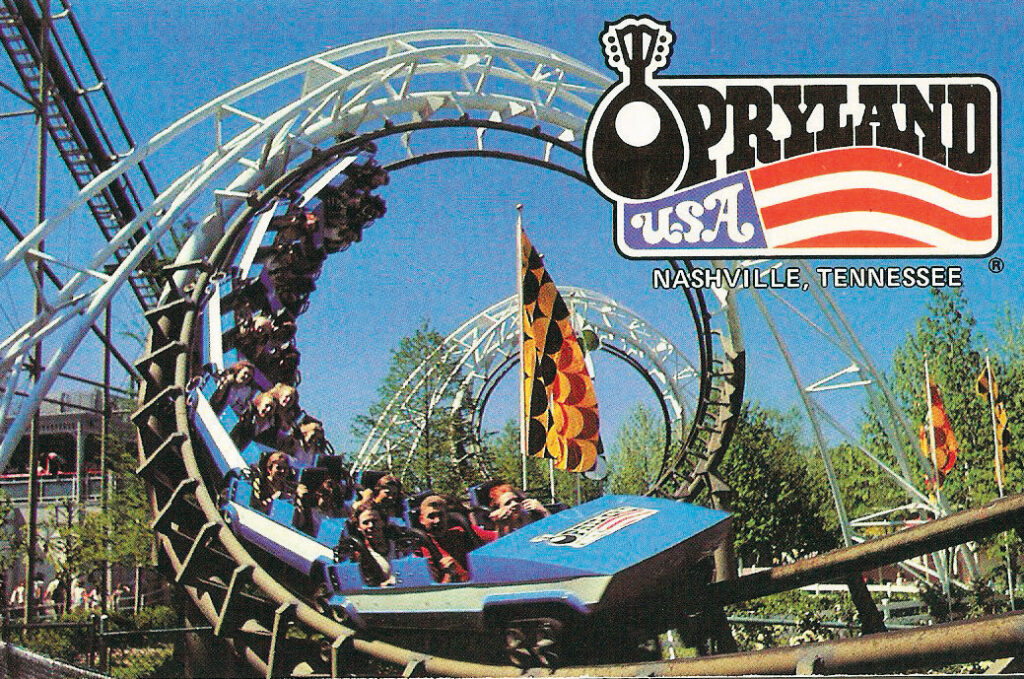

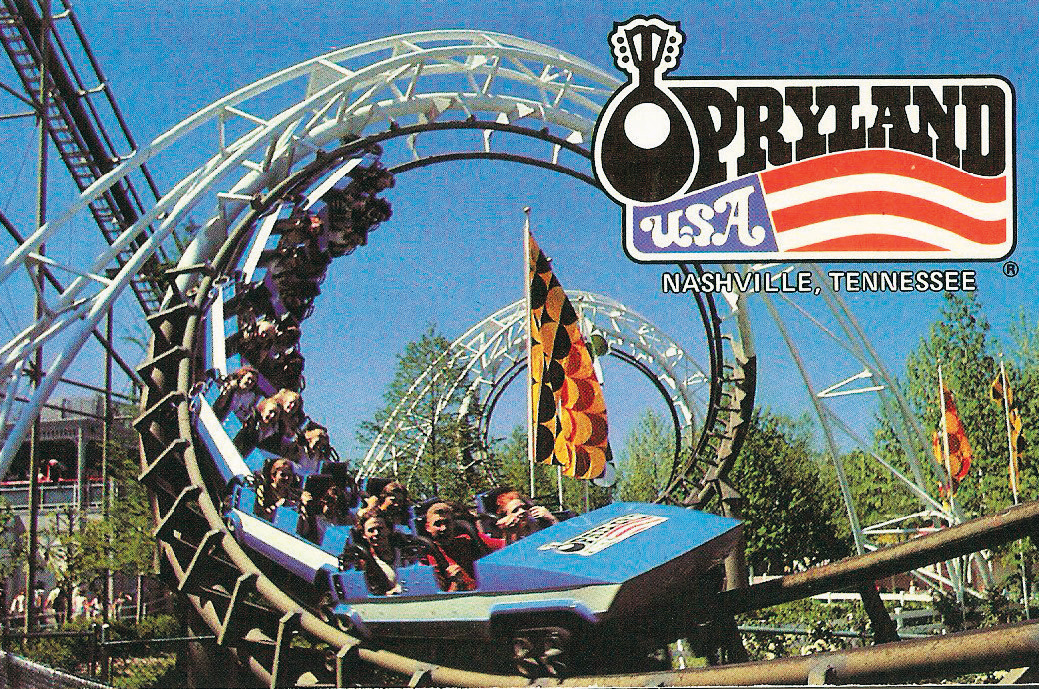

Back to the theme park: Thanks to Opryland USA, Nashville had something other Southern cities did not. Opryland’s visitors returned again and again and had the time of their lives, riding roller coasters such as the Wabash Cannonball and attending shows such as “I Hear America Singing.” Thousands of young people worked their first jobs at Opryland, selling cotton candy, putting tourists on a log flume or singing in a show. “When I came from high school, I only knew people from my high school,” said Ashland City native Velvet Hunter, who worked at Opryland for three summers in the 1980s. “When I went to Opryland, I met so many people my age from all over Nashville.”

For purposes of full disclosure, I should point out that I also worked at Opryland. For about two months in the summer of 1986, I was on the Opryland train crew. I stood in the train stations, sat on the back of the train and read the script they wanted us to read, and even sat up in the front and got to run the engine a few times.

I’m not going to go into the saga of why the Opryland theme park closed in 1997 (you can read the rationalization of it in my book). I will say, however, that I’ve never met a longtime Nashville resident who doesn’t have fond memories of the place and who doesn’t wish it was still open. If you don’t believe me, check out the Facebook groups that are devoted to memories of the park. Buy the paperback book (published in 2016) called “Opryland USA” that consists entirely of photos of the park. You can also check out the Nashville Public Television-produced documentary about the park, which contains quite a bit of home videos that people took while visiting the place.

See more photos of when Opryland opened from our June 1972 issue of the The Tennessee Magazine.