Whether you are an avid museum goer, a bit of a history buff or have never quite gotten over a childhood fascination with dinosaurs, stepping into fossil exhibits is always a blast from the past. Tennessee has many wonderful places you can visit to scratch that fossil itch. Here are three in particular — one from each region of Tennessee — that offer unique experiences that surely will leave you knowing more about Tennessee’s geologic history and wanting to learn even more.

The Gray Fossil Site and Museum has fossils of strange animals such as saber-toothed cats, bone-crushing dogs, massive mastodons and giant flying squirrels along with a rich fossil plant record, said Chris Widga, head curator at Gray Fossil Site and Museum.

“Going to a paleontological exhibit is like time traveling,” Widga said. “You walk into an exhibit and find yourself in the same place — but millions of years in the past. So it’s kind of like walking into a different world. The element of time travel is part of the visitor experience when you go to a paleontological museum, and you can take it with you when you leave. So you walk through our exhibits, you learn about what is underneath your feet, and then as you walk out the front door and look across the landscape, you’re like, ‘Oh, this is cool,’ because then you’re able to ‘time travel’ outside the museum as well. That’s one of the things that I think is really engaging about paleontological exhibits.”

Based in East Tennessee, the Gray Fossil Site is a two-museums-in-one experience. With its partnership with the Hands On! Discovery Center, visitors pay one price to get the benefits of both — one that features natural history and fossils and one with interactive science displays — a novel and innovative approach to museums, Widga said.

“It is definitely a neat, unique museum experience and something that, even if you are a regular museum-goer, is different,” he said.

The museum was built on top of a world class 5 million-year-old paleontological site, Widga said. The Gray Fossil Site was discovered in 2000 by the Department of Transportation as workers were widening a road near an accident-prone intersection, and the museum opened in 2007.

“We’re a museum built on top of a world-class fossil site,” Widga said. “It kind of makes us almost like a historic house museum but for fossils, and you don’t see very many of those, especially in the eastern U.S.”

Though many natural history museums drive 10 or more hours away to dig for dinosaurs, Widga said that at Gray, “We dig everything up in our backyard” with a staff of 20 to 25 paleontologists every summer.

“One of the comments that I get when talking to visitors is, ‘Wow! You have so many real fossils on display,’ and that’s intentional,” Widga said. “We have a lot of material; we have over 38,000 specimens from the site that we’ve excavated over the last 20 years. Our goal is to get those fossils on display and into a place where the public can see them.”

The Gray Fossil Site and Museum has windows into its prep lab and collections area, one of the few museums where visitors can watch it all happen — seeing how paleontologists clean up, stabilize and glue together fossils. The museum is also affiliated with East Tennessee State University, which has one of the most active paleontological research programs in the state and in the eastern U.S.

“All museums are local or regional draws, and if they’re doing their job well, they are pulling out the unique and interesting things about the surrounding landscape or the communities around them,” Widga said. “I think ours does that really well. Our focus is on natural history and the fossil record, and East Tennessee has a great fossil record that we highlight very well.”

Widga said that more than 100 species of animals and 100 species of plants have been recovered from the Gray Fossil Site, and of those species, 16 are completely new to science. The fossils found at the site are 5 million years old — meaning 60 million years after dinosaurs went extinct.

“We didn’t know anything about them before,” Widga said about these new species, “and this was the first and only place they’ve been described. The paleontology of the Gray Fossil Site is important to understanding how climate, animal and vegetation communities changed in the past. This is one of the things that is unique about this museum and unique about what we do.”

Gray Fossil Site’s red panda record — the best on the continent, according to Widga — is its “claim to fame.” The site boasts at least five individual red pandas, two of which have mostly complete skeletons, not just teeth, he said.

“If you see the Tennessee U-Haul vans with the red pandas on the side, that’s our red panda,” Widga said.

“There is definitely some value to fossils in our modern world,” Widga said. “I mean, we often think of museums and natural history museums and paleontological specimens and things like that: ‘Well, they’re interesting, but do they have any relevance to modern life?’ And they really do.”

Widga said we are at a time when we are looking at quite a bit of climate change and landscape change.

“Understanding how landscapes in East Tennessee adapt to changes in climate at the scale of centuries to millennia, the only way you can do that is through looking at fossils. This is the bread and butter of paleontological research,” Widga said.

At the Gray Fossil Site, researchers are looking into how the landscape of East Tennessee looked under a climate that was much warmer. The climate at the fossil site 5 million years ago was similar to East Texas or Southern Gulf Coast Louisiana — much warmer, much more wet — which is kind of hard to believe, Widga said.

“That gives us some insight into how these ecosystems worked, and it means that we’re not only time traveling back into the past, but we’re also trying to forecast how these landscapes might change in the future,” he added. “If I’m thinking about the application of what we do to modern life, that’s one of the major things we’re trying to understand.”

One place in Middle Tennessee where you can go to see fossils, including those of dinosaurs, is Earth Experience, also known as the Middle Tennessee Museum of Natural History. The museum is one of the only places in Tennessee where visitors can see actual bones from dinosaurs, said Alan Brown, executive director at Earth Experience.

“In my experience, there is no child between the ages of 5 and 10 who doesn’t go through some point absolutely loving dinosaurs, and learning about dinosaurs is kind of a way to start getting people interested in science a little bit,” Brown said. “Anything we can do to help encourage people to get interested in science is a very good thing.”

Earth Experience also has quite a few local fossils from here in Tennessee.

“Most of the fossils here in Middle Tennessee are a little bit too old to be dinosaurs — they’re from before the time of the dinosaurs — but there are still lots and lots of fossils found here in Middle Tennessee,” Brown said.

Middle Tennessee was underwater during the time of the dinosaurs, which is why dinosaurs aren’t found there, but there is an abundance of marine fossils, Brown said.

One dinosaur bone that was found in Tennessee is on display in Earth Experience’s collection. Brown said it is believed the bone was preserved because the dinosaur died near the shore and was washed out to sea, buried and fossilized. Though such fossils are extremely rare, a couple have been found in Tennessee.

“Here in Middle Tennessee, the rocks are just full of fossils, so I always tell people, ‘Just go out in your backyard and start looking at rocks, start flipping over rocks,’” Brown said. “You’re going to find all kinds of fossils if you just look, especially the little clams and snail shells and that kind of stuff, and then learn a little bit about them.”

Earth Experience visitors can look into the museum’s paleontology lab and see people working on actual dinosaur bones and fossils. Brown said not many museums offer such an intimate look into that process.

Another interesting aspect the Earth Experience has to offer is a dinosaur dig program where a team from the museum travels out West to dig for dinosaur bones every summer.

“Now it’s a little bit harder to find the dinosaur bones when we’re out in Montana, but it’s usually still a lot of walking and looking, and eventually as you cover enough ground, you’re going to come across something,” Brown said. “Individual dinosaur bones are actually fairly common out there. The complete skeletons are extremely rare.”

Brown said he still hasn’t found a complete skeleton even though he has been digging for quite awhile, but researchers find, on average, one dinosaur bone a day on the trip.

“The dinosaur digging is what kind of instigated the idea of starting the museum,” Brown said. “I have been digging dinosaurs now for about 14 years. I had been digging dinosaurs for six years before the museum started and was just wanting to share with the rest of the area some of the stuff we had been finding because there was no other natural history museum in Middle Tennessee and no real dinosaur museum in the whole state.”

Brown said he started the Earth Experience because he loves museums. The first thing he did when moving to Middle Tennessee was look for a natural history museum and, when he realized there wasn’t one, a few people got together to get one started.

“It’s been very well received,” Brown said. “I have people almost every day thanking me for what I do, so it’s very rewarding. There’s definitely a need for it; there’s a lot of interest in museums.”

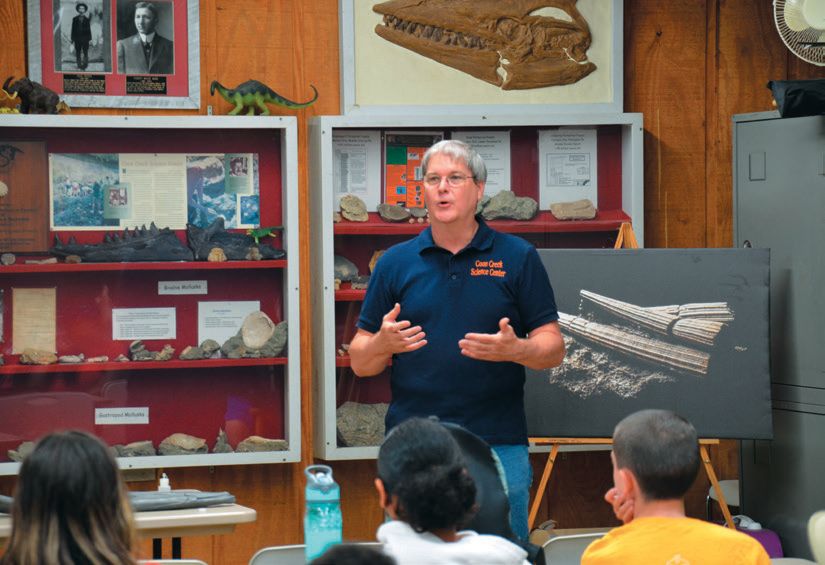

In West Tennessee, the University of Tennessee at Martin Coon Creek Science Center is a world-famous site in the paleontological world, and people can visit if they plan ahead. “We have scientists from all over the world coming here to study it,” said Alan Youngerman, director of UT Martin McNairy County Center/Selmer, which is over the Coon Creek Science Center.

The fossils found at the site are 72 million years old — from the Cretaceous period, a geologic time period that included the dinosaurs, but at the time the area was part of a vast sea that covered all of the middle part of North America. So the fossils reflect the marine life during that time period. The Coon Creek site was identified as a “type section” for Cretaceous fossils for that period of time, Youngerman said.

“When it reaches that status of a type section, anybody in the world studying these Cretaceous fossils in this timeframe has to compare their work back to the Coon Creek deposit,” Youngerman said. “That’s why it’s so important.”

In order to visit the site, visitors must call ahead to make reservations. On the third Saturday of each month, community days include sessions at 9 a.m. and 1 p.m., and Coon Creek staff members try to schedule smaller visiting groups on those days.

“We try to limit the group size to 20 to 25 people so everyone gets a really good experience and a lot of one-on-one time with either the interns or the scientists who are there,” Youngerman said.

Visitors meet in the dining area at the site where fossil specimens are on display in an exhibit. They are then led on a creek walk where they can find and collect their own fossils to keep as mementos (unless they find something scientifically significant, of course).

“Unlike the Gray site and other sites, our visitors are allowed to keep most fossils that they find,” said Michael Gibson, paleontologist for UT Martin and director of the UT Martin Coon Creek Science Center. “We are able to allow visitors to keep material because of the size of the fossil deposit at Coon Creek, which is over 230 acres, and abundance of fossil shells.

More than 700 different species of fossils have been identified at the site, and that number grows every year, so Coon Creek is a very rich fossil site, Youngerman said.

“It’s designated a ‘lagerstatten,’ which is a loosely translated German term for ‘motherload,’” Youngerman said. “Certain fossil deposits around the world obtain that designation, and this is one of the few ‘lagerstatten’ deposits from which you can actually collect and take fossils home.”

Coon Creek can also handle larger groups such as church or school groups, but those have to be scheduled out well in advance and will not fall on community days.

“I had a homeschool group there on Monday, and they just really had a blast,” Youngerman said. “They had such a good time getting out and actually exploring and finding their own fossils and learning how to preserve them. It’s something that they’ll keep for a lifetime.”

Youngerman said one of the mothers in the group had visited decades ago as a child herself and still had her fossils from when she visited.

“To me, geologically speaking, the present is the key to the past, so when you’re looking at things in the past, you’re seeing the same things that are happening in today’s environment,” Youngerman said. “You’re seeing the same things in the seafloor sediment that are going on today, and so you can compare the 72 million-year-old seafloor that you’re walking on to today’s seafloor, and you’re looking at some of the same aquatic organisms.”

At the Coon Creek fossil site, you can find fossils of organisms like clams, oysters, shrimp, crabs and lobsters that can compare to today’s organisms, Youngerman said.

“The site is home to the Official State Fossil of Tennessee, which is an extinct bivalve called Pterotrigonia thoracica,” Gibson said. “Visitors may collect their own.”

Large marine reptile remains, including those of mosasaurs, a plesiosaur and marine turtles, are preserved on the site, Gibson said. Fish, including sharks, are also found at Coon Creek.

“The biodiversity at the time was tremendous compared to today,” Youngerman said. “There was just an explosion of life.”

Tennessee’s geologic record shows that it has been mostly ocean environments for most of its billion-year history, and the Coon Creek fossil site represents the very warm climate that has dominated Tennessee throughout time, which included sea levels much higher globally than they are today, Gibson said, adding, “Today is the exception to that trend.”

“I guess as humans, we have our egos, thinking, ‘Well, this is how it has always been because it’s been this way my whole life,’” Youngerman said. “Well, we’re just looking at that brief fraction of a second in geologic time, and it’s really neat to see what the world looked like, where the water was and what was going on 72 million years ago.”