I recently set out to trace the history of the acre on which my house sits — back to its Revolutionary War-era land grant. When I started, I knew little about what I’d find. I knew my address and when I’d bought the house, and I had heard a story or two from some of my older neighbors. But that’s about it.

I’ll tell you some of the high points I learned and some of the myths I dispelled. Then I’ll give you some tips that might help if you ever want to do such a thing.

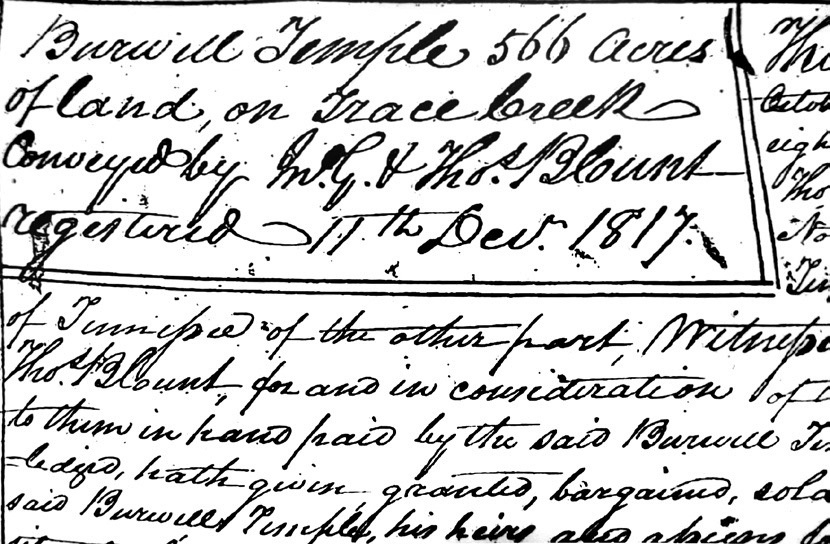

The land on which my house now sits in Williamson County was part of a land grant issued by the state of North Carolina in 1793 to brothers John Gray Blount and Thomas Blount. These speculators apparently obtained land grants from Revolutionary War veterans who didn’t want to move to Tennessee. They then sold land a few years later, reaping profits in the process. The Blounts, siblings of Southwest Territory Gov. William Blount, did this sort of thing all over the state and at one time owned hundreds of thousands of acres.

In October 1817, the Blount brothers sold most of this particular land grant for a total of $800 to a man named Burwell Temple. Subsequently, I’ve found four different transactions between 1818 and 1827 in which Temple sold parts of the property — those being 55 acres, 100 acres, 130 acres and 67 acres. Those four transactions added up to $1,500, so Temple knew what he was doing.

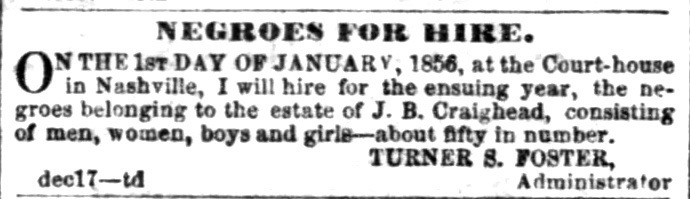

I’ll admit that I’m not exactly sure when the land on which my house sits sold between 1817 and 1850. But I do know that by 1850, my yard was part of a 166½-acre farm owned by John B. Craighead — whose wife Lavenia was the 10th of Nashville founder James Robertson’s children. After J.B. Craighead died, (according to a newspaper item) his widow Lavenia “farmed out for hire” her 50 slaves through her late husband’s estate. Three years later, she ran an advertisement in an attempt to sell her land, pointing out that the property had “about 700 yards of stone fence.”

Speaking of historical mysteries: In my backyard is a sunken pathway that my late neighbor once told me was “an old Civil War road.” A few years ago, I was so excited about this possibility that I bought a metal detector. On a wonderful day in December 2019, we dug up a lot of farm waste such as several plow spokes.

However, in the process of researching the history of my land, I found (on a topographical map from 1901) that there was a driveway cutting through what is now my backyard, leading to a farm building. So the sunken path was probably not a public road, nor as old as my neighbor thought. It was just a farm road, apparently a place where they dumped trash.

Back to the history: In 1867, Lavenia Craighead’s daughter, Georgiana Hill, sold the farm to Henry Potts, whose family operated a livestock farm here for the next 55 years. At least one member of the family died in the process: John T. Potts bled to death in 1928 from an accident in which a large hog severed an artery in Potts’ thigh.

The Potts family sold the farm to Flaud Burnett in the 1920s. Burnett’s family ran the farm for nearly 40 years, and in the 1930s and 1940s specialized in the breeding of prized mules — the most famous being a 1,150-pound specimen called General Logan Again (the mule’s father was called General Logan). When Burnett passed away in 1967, the property was put in a trust, and his three sons hired a developer to subdivide it into residential lots. My house was built in 1972, and my wife and I are its third owners.

More discoveries about the land I now call mine

I live close to the northern terminus of the Natchez Trace Parkway. However, the original Natchez Trace (or “road to Natchez,” as it was called in the early 1800s) was at least 4 miles east of both the parkway and my land. The real “road to Natchez” left Nashville heading south toward Franklin, along what is now known as Hillsboro Road (Highway 431). It then either veered southwest at present-day Highway 46 or went all the way to Franklin and veered southwest there. Why the federal government extended the Natchez Trace Parkway to the Bellevue section of Davidson County is a great mystery.

The land on which my house sits was originally in Williamson County. Sometime in the 19th century, it was annexed by Davidson County, and sometime in the early 20th century, it was moved back to Williamson County. Neither I nor anyone in the Williamson County or Davidson County Registry of Deeds offices have been able to ascertain why.

Finally, the earliest detailed map of this area is the 1878 one made by Beers & Company. It shows hills, roads and driveways and labels each house with the name of the family who lived there. It struck me as I looked at this map that just about every house, bridge and road on it is gone or has moved. However, the 1878 map shows where the creek behind my house forks, and today it forks in the exact same spot as it did then.

History comes and goes, but the creek stays the same.