“The Freedom Riders, expelled from A&I, were restarting the sit-ins, and I wanted to participate, so we got a short intro to nonviolent protests at First Baptist (Church) Capitol Hill by Lewis and other leaders, then made our way downtown,” she says, looking back on her first experience with the civil rights movement. “We sat at the counter, and the next thing I knew, several busboys physically picked me up like a sack of potatoes and threw me out on the street like I was trash. I didn’t fight back, but racial slurs and that violent physical incident triggered me. From then on, I wanted to do everything I could to support and influence the movement.”

The then-student at Tennessee Agricultural & Industrial University (now Tennessee State University) had moved to the South from Detroit to attend college and was soon met with the worst kind of culture shock she had ever encountered: overt segregation and racial discrimination.

More than six decades later, the former educator continues to speak about civil rights, recalling those early days working side-by-side with Lewis (who later became a congressman from Georgia), Bernard Lafayette, C.T. Vivian, James Lawson, Marion Berry and others.

“At that time, the whole city was in an upheaval, and I felt I had no other moral choice but to join the movement knowing full well I could be expelled from college,” McKissack says. “I knew I had the courage and strength in my heart to carry on and stand up for racial equality and justice.”

Her actions and those of other members of the civil rights movement are commemorated in 14 sites on the Tennessee portion of the U.S. Civil Rights Trail, created by Travel South USA starting in 2018.

In Nashville, the sites are the Civil Rights Room at the Nashville Public Library, Clark Memorial United Methodist Church, Davidson County Courthouse/Witness Walls, Woolworth Theatre, Fisk University, Griggs Hall at American Baptist College and the National Museum of African American Music.

“In 2021, the city renamed Fifth Avenue John Lewis Way to memorialize the late congressman and civil rights leader who died that year,” says Marie Sueing, chief diversity officer for the Nashville Convention & Visitors Corp. “A historic marker was placed at Sixth Avenue North and Commerce Street where the old Greyhound bus station was located. That’s where a young Lewis boarded a bus to join the restarted Freedom Rides in Alabama.”

In the same area at the corner of John Lewis Way and Commerce Street, a four-story mural commemorates Lewis and other Freedom Riders C.T. Vivian, Ernest “Rip” Patton, Diane Nash, the Rev. Kelly Miller Smith, the Rev. James Lawson and Kwame Lillard.

Across the South in the 1950s and 1960s, nonviolent protests continued, and Tennessee became a focal point of the movement, particularly in Clinton/Anderson County where 12 students successfully integrated Clinton High School on Aug. 26, 1956.

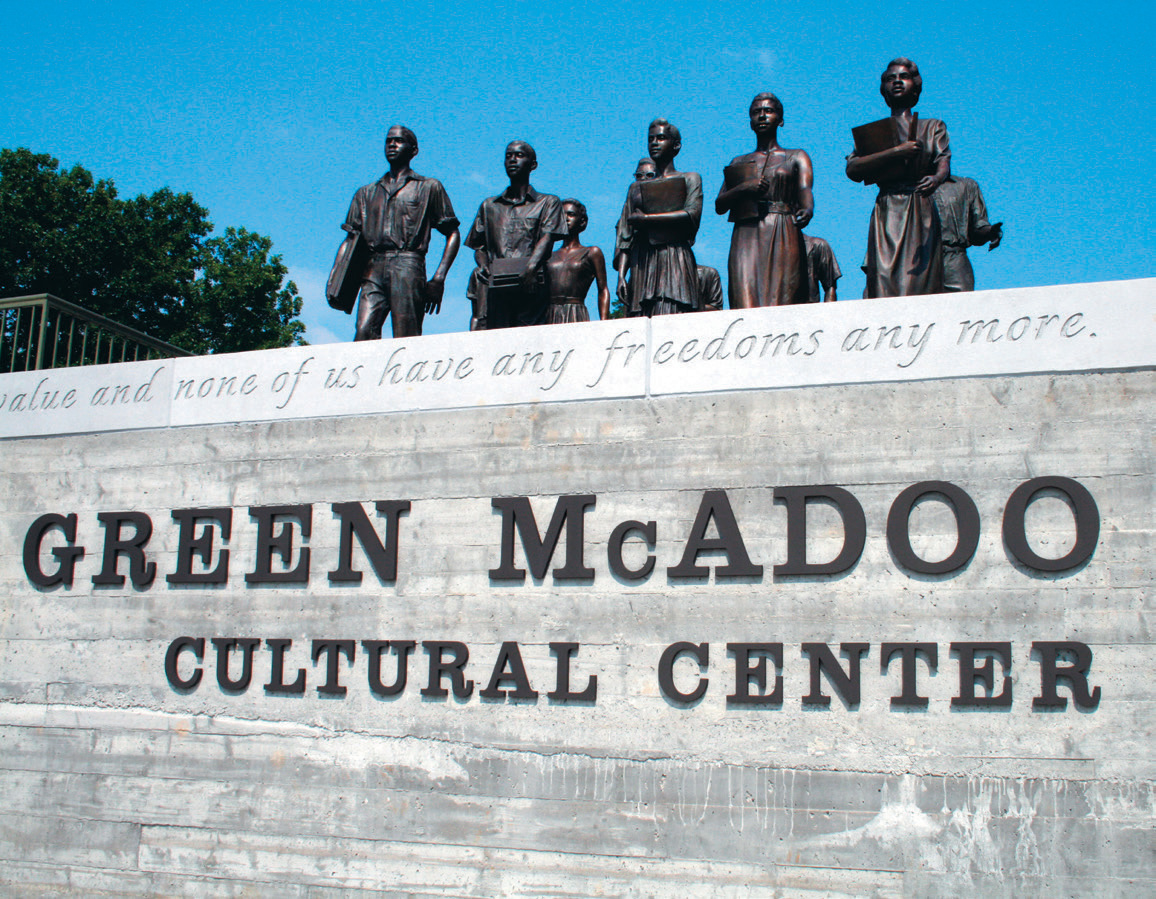

“Now known as the Clinton 12, these courageous students made it the first desegregated public high school in the South,” says Stephanie Wells, director of the Anderson County Tourism Council. “Their story is told in the Green McAdoo Cultural Center, which opened in 2006 to celebrate the 50th anniversary of their actions.”

The center is located in the former Black school for grades K-8. Outside, 12 life-sized bronze statues greet visitors. Inside, a 1950s-period classroom takes visitors back to education in the mid-20th century.

Biographies and photos of the Clinton 12, a comprehensive history of the town’s role in the civil rights movement and interactive screens re-create the faces, names and places in Anderson County that contributed to national change.

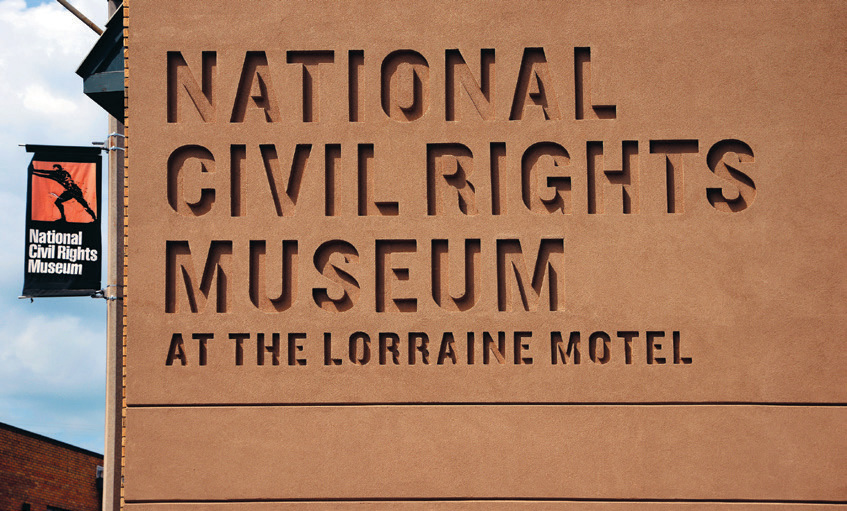

The world’s eyes turned to Memphis on Thursday, April 4, 1968, when Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated while standing on his balcony of the Lorraine Motel.

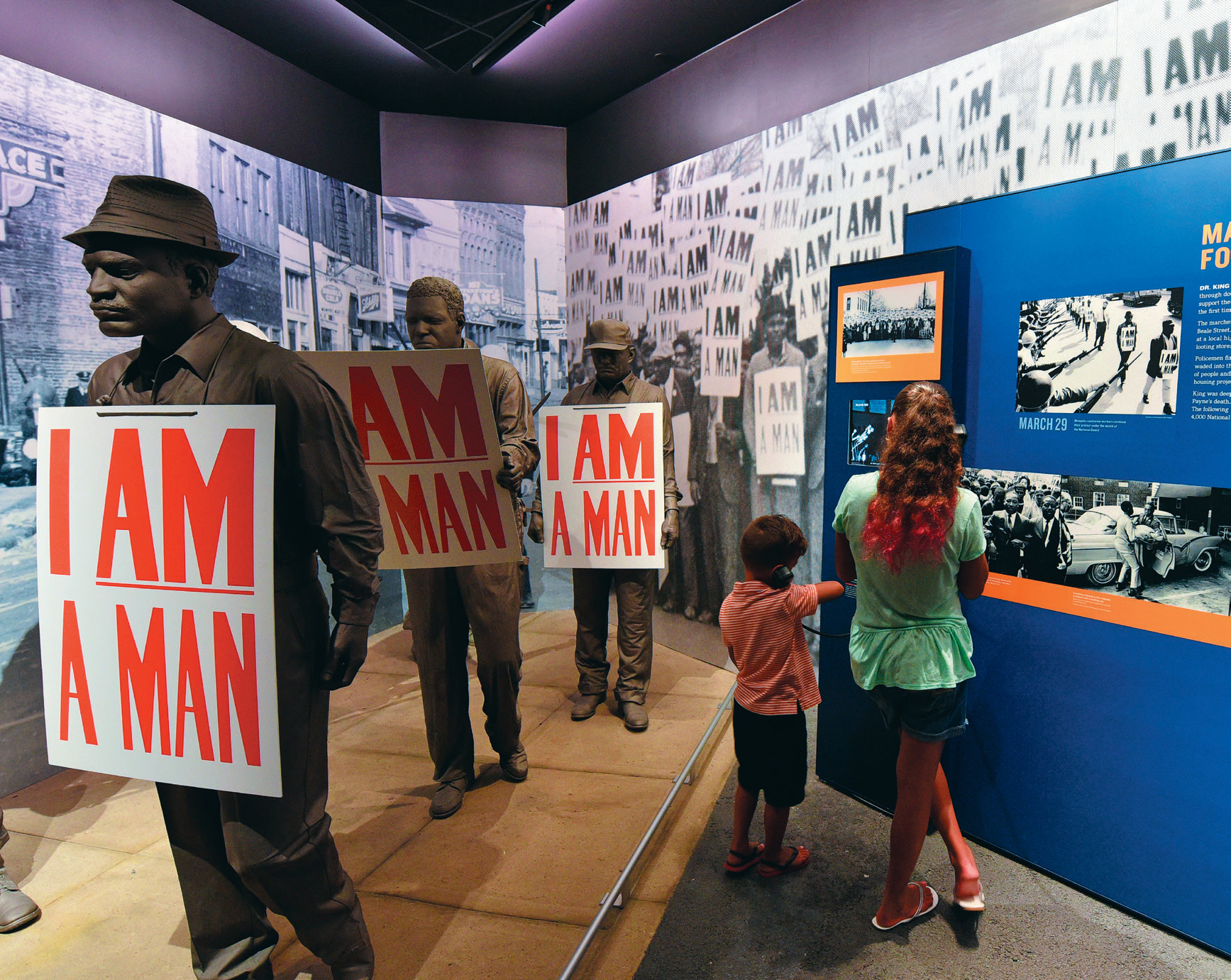

“He had just delivered his ‘I’ve Been to the Mountaintop’ speech in support of the sanitation workers’ strike in Memphis the day before,” says Connie Dyson, marketing communications manager for the National Civil Rights Museum, located in the former Lorraine Motel.

“In that speech, he said, ‘Like anybody, I would like to live a long life. Longevity has its place. But I’m not concerned about that now. I just want to do God’s will. And He’s allowed me to go up to the mountain. And I’ve looked over. And I’ve seen the promised land. I may not get there with you. But I want you to know tonight, that we, as a people, will get to the promised land!’”

The National Civil Rights Museum at the Lorraine Motel is one of the most visited restored civil rights landmarks in the nation. The Mason Temple Church where King gave his “I’ve Been to the Mountaintop” speech the night before his assassination is frequently visited as well.

In addition to the National Civil Rights Museum at the Lorraine Motel, sites on the U.S. Civil Rights Trail in Memphis are the Beale Street Historic District, Clayborn Temple and I Am A Man Plaza, Mason Temple Church of God in Christ, Stax Museum of American Soul Music and WDIA Radio Station.

After spending the past 63 years immersed in the civil rights movement, including being on the forefront of school desegregation as a history teacher for 47 years in Tennessee, Ms. McKissack is reflective but not complacent about the movement’s legacy.

“People need to continue to teach and learn positive conflict resolution to move forward, and I just want people to be able to get along,” she says. “Racism will not go away; evil is out there. But remember to stay vigilant and never give up. Don’t ever let anyone turn you around from justice.”