The history world makes a big deal of anniversaries such as the centennial of the passing of the suffrage amendment and the 150th anniversary of the Civil War. I prefer to look back at years that don’t necessarily jump off the history book pages. Allow me to peruse through 1823 — a year in which the state capital was Murfreesboro and the governor was William Carroll.

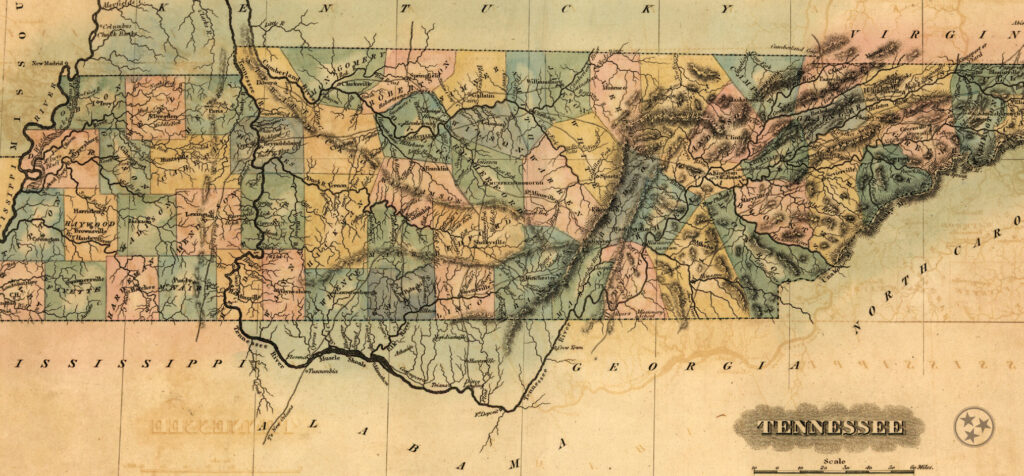

In 1823, West Tennessee was only five years removed from its purchase from the Chickasaw. People were moving into every corner of West Tennessee, forming communities such as Memphis, Jackson and Dyersburg. That year, no fewer than eight West Tennessee counties were formed — Dyer, Gibson, Hardeman, Haywood, McNairy, Obion, Tipton and Weakley.

Two hundred years ago, Middle Tennessee was thrilled about the results of the most recent census while East Tennessee was miffed about it. According to the 1820 census, Maury, Williamson, Davidson, Rutherford and Sumner counties each had about 20,000 residents. Knox County, meanwhile, led East Tennessee with only 13,000 people.

Why? It had to do with the limitations of the Tennessee River. Only a few years earlier, the Constitution became the first steamboat to make it up the Cumberland River to Nashville. By 1823, steamboats such as the Rambler and General Robertson regularly brought goods and passengers to and from Nashville. At the same time, merchants of Knoxville were hampered by the fact that steamboats couldn’t make it up the Tennessee River (and wouldn’t for several years). Crozier and Martin, Knoxville’s dry goods merchant, announced that its products came from Philadelphia and Baltimore — which meant they came overland, not upstream.

In desperation, East Tennessee’s business leaders threw their support behind the idea of digging a canal to connect the Ocoee River in southeast Tennessee to the Conasauga River, which flows south into the Coosa River and, eventually, Mobile Bay. The canal venture was doomed for two reasons: One, the federal government didn’t want to pay for it, and two, the Cherokee didn’t want it on their land.

In 1823, newspapers in Middle Tennessee began running ads for a partnership of two lawyers, both of whom would eventually become famous. One was Aaron Brown of Pulaski — later the 11th governor of Tennessee. The other was James K. Polk — later the 11th president of the United States.

Speaking of the number 11, that’s how many members of Congress Tennessee had. Andrew Jackson, famous for his military service in the War of 1812, was one of Tennessee’s U.S. senators in 1823. Another veteran of that war, though little known, was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives by the voters of Blount County. His name was Sam Houston.

Houston had nothing whatsoever to do with it in 1823, but Texas was very much in the news by then. The phrase “gone to Texas” had entered the state’s vernacular about two years earlier when Stephen Austin first invited people to his colony. In November 1823, newspapers in Tennessee published a letter from Austin, which added to the migration. “I want settlers of respectability, and if you or your friends will join me, I will allow you all the privileges in my power,” he wrote. “The land will cost 12½ cents an acre.”

Speaking of names associated with both Tennessee and Texas, West Tennessee had a state House member named David Crockett who made the news once or twice in 1823. On Sept. 18, Crockett said on the House floor he was “opposed to divorces in general” — which was relevant because back then, the General Assembly granted divorces. Also in that session, Crockett proposed a bill to end the practice of imprisoning debtors.

Two centuries ago, our state got its first history book. John Haywood’s “Geological and Aboriginal History of Tennessee” was released in November 1823. Accurate or not, Haywood’s explanation of some of the early events in Tennessee history remains, in many ways, the official account — the one told on historic markers, for instance. Leather-spined first-edition copies of Haywood’s book can be purchased from book collectors today for prices starting around $10,000.

Two hundred years ago, the Nashville area boasted Tennessee’s first two resorts. Not much by our standards today, both consisted of cottages that could be rented near mineral springs. One was Robertson Springs, located halfway between Nashville and the Kentucky border. The second was simply known as the Fountain of Health, and it was in the eastern part of Davidson County. According to ads, the Fountain of Health could cure everything from rheumatism to asthma to gonorrhea. People came from as far away as Virginia to drink its waters.

In 1823, citizens of Nashville began to raise money for the city’s first hospital. Since governments were not yet in the business of funding such things, the leading citizens tried to raise the funds through a lottery.

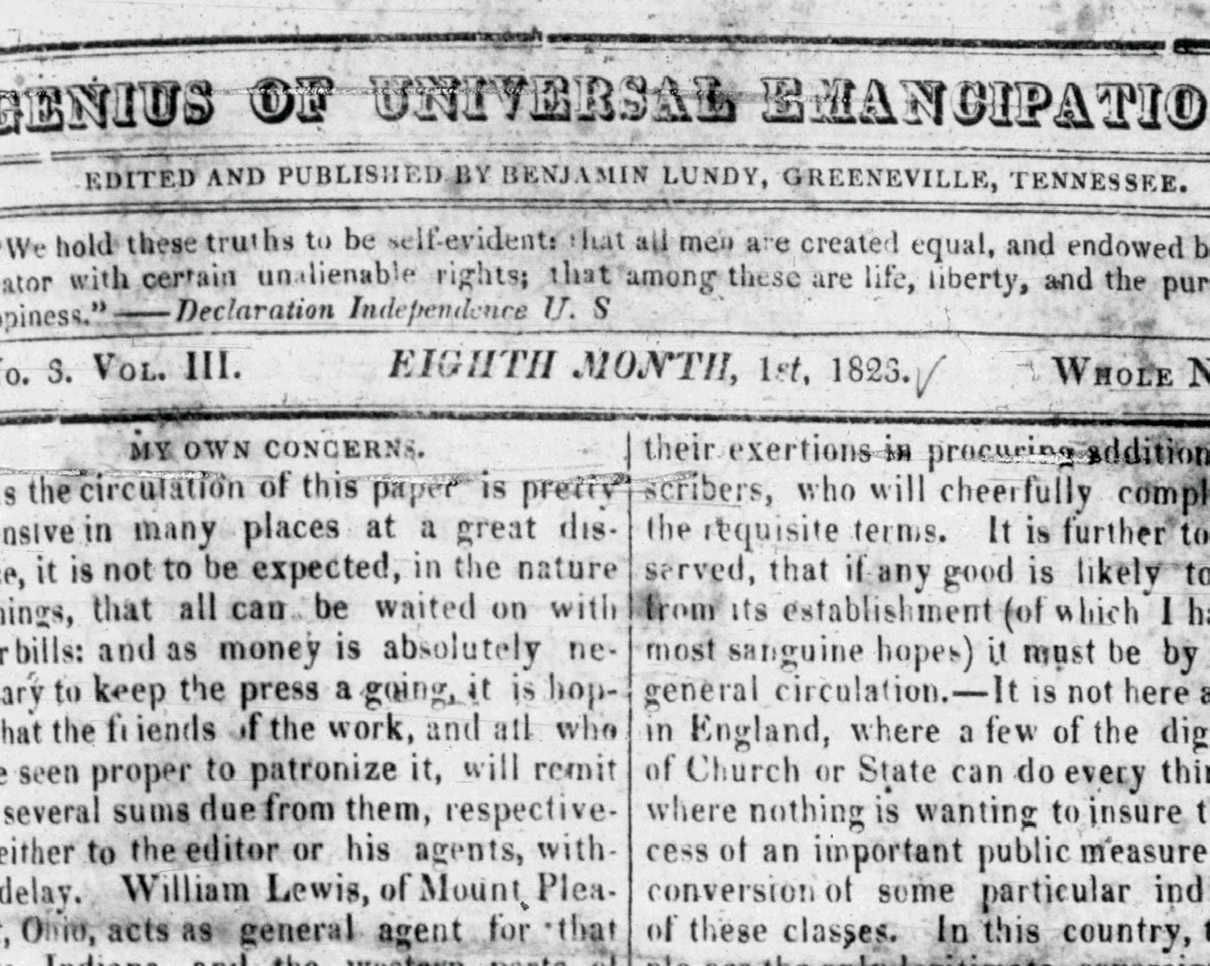

Two hundred years ago, Greeneville had an abolitionist newspaper. Started by Quaker Benjamin Lundy, the Genius of Universal Emancipation was Tennessee’s second newspaper devoted solely to the cause of antislavery. It was inspired by the first — the Manumission Intelligencer, which had been started by Jonesborough’s Elihu Embree a few years earlier. Like Embree’s paper, the Genius of Universal Emancipation did not remain in Tennessee for long. Lundy moved the business to Maryland the next year.

As for the rest of Tennessee’s newspapers, we can safely place them in the “proslavery” category in 1823. The Nashville Whig, Nashville Gazette, Knoxville Register, Jackson Pioneer and every other newspaper in the state ran slave-related ads of all types, including runaway slave ads, “slave for sale” ads, “slave for rent” ads and others. One of the more interesting ads ran in the Nashville Whig in April and offered $100 for the return of three enslaved men named Trouble, Philip and July. It was paid for by the slaveholder — Chickasaw Chief George Colbert, for whom Colbert’s Ferry on the Tennessee River in northwest Alabama was named. “I am disposed to think they will push for some of the free states and may probably attempt to get to the western side of the Mississippi,” said Colbert.

We don’t know whether Colbert ever saw Trouble, Philip and July again. But we do know that, 15 years later, the Chickasaw chief himself moved west of the Mississippi River in the forced migration known as the Trail of Tears.