Reflecting on life for Tennessee pioneers

Authors and columnists have a tendency to write about famous battles and famous people. We write about events we deem important.

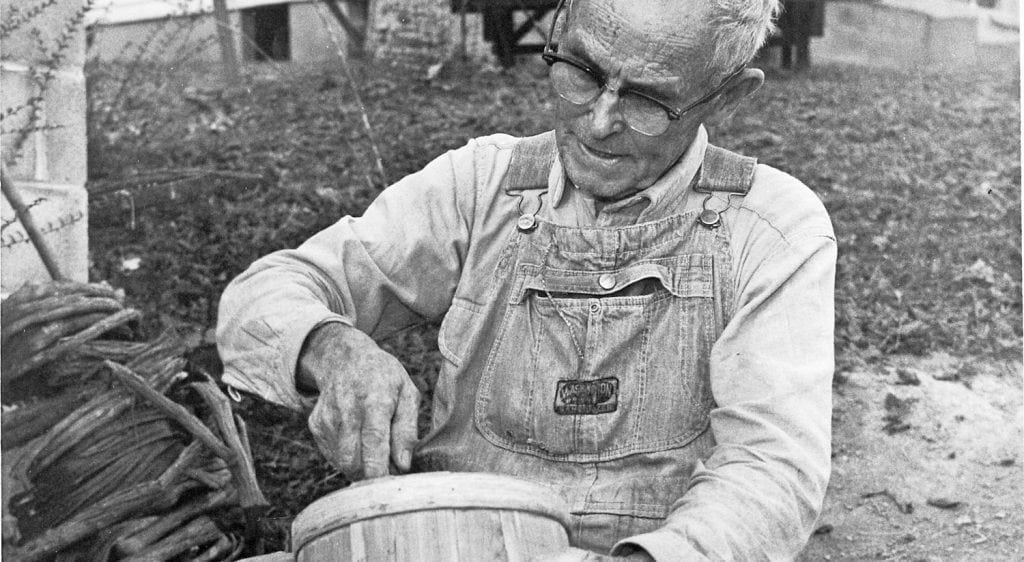

I recently came across a book that made me aware of how much we all neglect the topic of day-today life. “Alex Stewart: Portrait of a Pioneer” was written 30 years ago by John Rice Irwin, founder of Clinton’s Museum of Appalachia. Irwin was originally drawn to Stewart because of his incredible reputation as a cooper. Using hand tools, Stewart made everything from furniture to weapons to toys out of wood, demonstrating skill and craftsmanship that eventually led to his being recognized by the National Endowment of the Arts.

Along the way, Irwin began accumulating anecdotes from Stewart about what life was like in remote and mountainous Hancock County in the early 1900s. “The more I talked with Alex, the more I realized I was talking with a man straight from pioneer America,” Irwin wrote. “Indeed, the conditions from which he sprang were as stark, dramatic and unbelievable as the conditions 200 years earlier in more accessible parts of this country.”

Stewart was born in the Newman’s Ridge area near Sneedville in 1891 and lived there practically all his life (he died in 1985). “Alex Stewart: Portrait of a Pioneer” is a series of transcribed interviews with him. Here are a few of the tidbits about life in that part of the state that I gleaned from the book:

To feed his family, Stewart worked as a sharecropper, coal miner, railroad worker, logger, log rafter, medicine man, cooper and even well digger. “I’ve rolled in the bed many a night, studying how I was going to feed my family the next day,” he said.

In Stewart’s youth, there were no stores near his home, and almost no one had money anyway. People survived by hunting, fishing, gathering and harvesting whatever they were able to grow in the woods or the small farms they created on the steep, rocky ground of Hancock County. As a result, things that seem like simple pleasures to us today — biscuits made out of flour, for example — were rare luxuries back then. “Ninety-five percent of the people never had biscuits,” Stewart said. “They just had cornbread, three meals a day.”

In Stewart’s youth, one of the leading causes of death was parasitic worms. “They (worms) killed lots of children,” Stewart said. “I’ve been to children’s buryings where they wasn’t nothing in the world wrong with them but worms.”

The Newman’s Ridge area of Hancock County was so remote that there were no doctors. Any ailment — regardless of its severity — had to either run its course or be treated with a natural remedy. Stewart goes into detail about the medicinal qualities of plants such as hemp, sarsaparilla, pine, boneset, goldenseal, wild cherry and angelica. “Back then, people didn’t go off (to a doctor),” Stewart said. “They went to the woods and got their medicine and made it. And they wasn’t nearly as much sickness and disease as they is today.”

There were no churches near Newman’s Ridge in the early 1900s. Rather than go once a week for a service lasting a few hours, Stewart’s grandparents would walk 20 miles to church events that lasted for days. “Grandpap and Grandma would go over to Jonesville to camp-meetings at certain times of the year,” Stewart recalled. “They’d stay there several days with one of his brothers.”

Stewart’s first schoolhouse had no furniture and no heating. His first teacher had no schoolbooks and no paper with which to teach. “I was the second boy in school that had a spelling book,” he said. “There was several of us boys that studied out of that book, and the teacher, she borrowed it and teached from it.”

For many poor families in Hancock County in that era, death from cold was a real possibility. “There was two or three women that froze to death right up here on top of this ridge,” Stewart said. “I remember like it was yesterday, when a woman and her two children froze to death. She lived in a little log house and had no bedcovers and no way to get wood for a fire. It come a real cold spell, and they just froze to death.”

Since so many people found and prepared their own foods, built and maintained their own homes and furniture, made their own clothes and had no electricity, idleness and leisure simply weren’t part of culture. Almost all social gatherings had to be structured around a task such as a corn-shucking or a cabin-building. Perhaps the best indicator of this is something Stewart recalled about his grandmother. “What a working woman she was,” he said. “She would never stop. You would never catch her idle. If you wanted to talk with her, she’d get her chair and her knitting or something and set down and knit as hard as she could. She’d be setting there seeding cotton or carding wool or doing something.”

In the early 1900s, when many people were buried in that part of Tennessee, “somebody would just pick up a rock and set it up (to mark the grave). They never thought of having any lettering cut on it. Ole Lou Trent was the first man I knowed of who had what you’d call a regular tombstone. They put up a rock at his grave and it had his name, his date of birth and all. Why, a lot of people would come down there just to look at that tombstone. They’d never seen one before.” This observation reminds us why we simply do not know where many Tennesseans were buried.

As the best-known cooper in the county, Stewart was often called upon to make coffins, a sad task that sometimes left indelible memories. “They was a Maxey boy come up to my place one time to get me to make a coffin for his twin babies,” Stewart recalled. “We went and got the lumber and I made an awful nice coffin. I made it wide at the shoulder and barely sloped it toward the feet. Made it look real good. I lined the outside with black cloth, and the inside with white cloth, and I got two cotton pillows for it. I’ve thought about that a lot — how them two twin babies looked laying there in that coffin side by side.”

Finally, in spite of what people want to believe, the traditions we now associate with Christmas were not part of the culture that Stewart experienced as a child. “The first Christmas tree ever I knowed of was put up by the Presbyterians who had come in here and built a church house down on Blackwater,” Stewart said. “I’s about 10 years old, and nobody had never seen such before.” And as for presents? “The first present I ever remember Pap getting us for Christmas was a little candy and an orange … I saved that candy and took a little bite off it every once in a while. I don’t know how long it lasted me. And they didn’t have no decorations along back then. That come in later on.”

Alex Stewart died in 1985. Many of those who visit the Museum of Appalachia today regard some of the amazing wooden tools, furniture and toys as his main gift to the world.

I see him differently. The anecdotes, stories and wisdom of Alex Stewart should make us all realize how lucky we have it. To me, that’s a pretty great Christmas gift.