There’s been a lot of wrangling about what to do with the bust of Nathan Bedford Forrest in Tennessee’s State Capitol.

Detractors say it needs to be taken down — arguing that Forrest made a fortune as a slave trader, was a leader in the Ku Klux Klan and that the Confederate soldiers under his command committed a terrible war crime at Fort Pillow.

Defenders of his likeness claim Forrest’s remarkable record as a cavalry commander and Tennessee’s most famous Confederate general justifies the statue. They say he should remain because the history he represents can’t be erased.

Some of these arguments were repeated at February’s meeting of the Tennessee Capitol Commission. But after an hour of testimony, the commission postponed a decision on what to do with the statue.

Perhaps some background on the statue and others like it can help settle this argument.

During the first 75 years of the Capitol’s existence, there was more emphasis on monuments outside than inside the building. The outdoor statues of Andrew Jackson, Sam Davis and Edward Carmack all predate World War II while the grave of James K. Polk was moved to the Capitol grounds in 1893.

Currently, there are statues of eight famous Tennesseans in the hallway between the House and Senate chambers. There is also a framed sculpture that depicts Tennessee’s 1920 passage of the suffrage amendment, a framed sculpture that represents former slaves voting in Tennessee after the Civil War, a bust of Sequoyah in the room across from the Senate chamber and a bust of George Washington on the landing between the first and second floors.

These monuments were all put up at different times, and there does not appear to be a record of what was present in the Capitol at different times in Tennessee history. (We have no way of knowing what statues or busts, if any, were in the Capitol in 1910.) However, we can piece together much of what’s happened in the last 90 years:

The George Washington bust was presented to the state of Tennessee by the National Society of Colonial Dames in Tennessee on the 200th anniversary of his birth in 1932.

Inspired by this event, the Ladies Hermitage Association presented a bust of Andrew Jackson (by Belle Kinney) on the 118th anniversary of the Battle of New Orleans (Jan. 8, 1933). This bust remained in the Capitol for years but is now at the Tennessee Performing Arts Center.

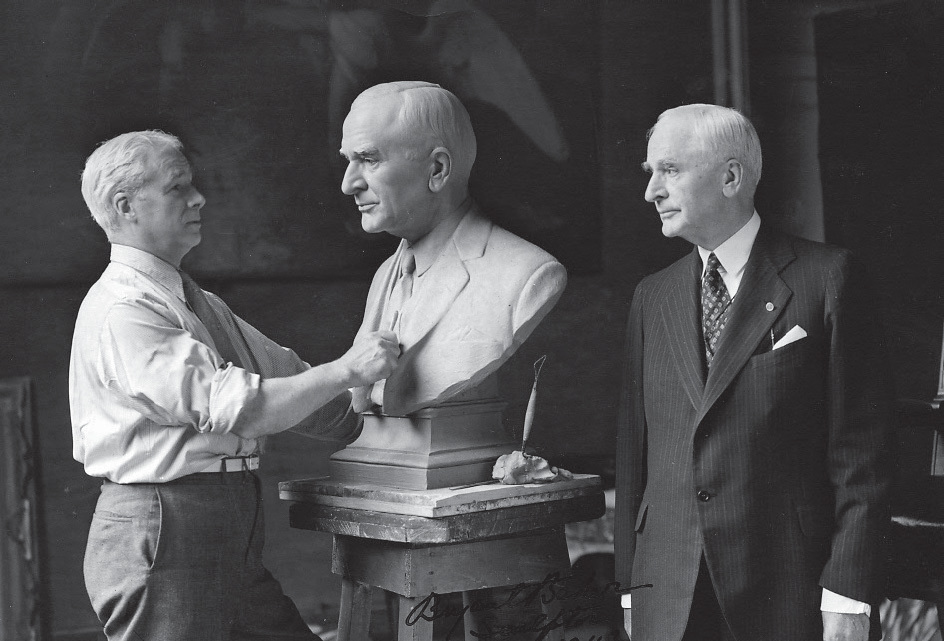

Secretary of Sate Cordell Hull poses with sculptor Bryant Baker as his bust nears completion for inclusion in the State Capitol.

Busts of former governors (and siblings) Robert Love Taylor and Alfred A. Taylor were created by Mary Hooper Donelson and placed in the second-floor hallway in 1935. These would remain until the 1980s but at some date were moved downstairs (where they are today).

In 1941, a second bust of Jackson was created by sculptor Puryear Mims and unveiled at the Capitol. This is one of the two Jackson statues still in the second-floor hallway.

In 1944, the Tennessee Historical Commission announced plans to create a gallery of Tennessee naval heroes in the Capitol. Statues in this collection were to be housed in the gallery between the House and Senate chambers.

This gallery was to include, among others, World War I hero Albert Gleaves, former U.S. Navy Adm. David Farragut and Mathew Maury, a Tennessean known as the “Pathfinder of the Seas” because of his achievements in meteorology and oceanography. Gleaves’ statue, created in 1939, was the first to go up. At the state’s sesquicentennial celebration in 1946, the statues of Farragut and Maury were unveiled. However, for some reason, the idea of a “Harbor of Tennessee Heroes” fizzled out after that.

Why? No one knows. Maybe Army veterans didn’t appreciate the idea. Maybe the General Assembly didn’t want to turn so much space over to war heroes with limited connection to Tennessee. In any case, Gleaves, Farragut and Maury remained, but the other sculptures of naval heroes originally envisioned as part of the gallery were never created.

The state also unveiled a bust of Secretary of State Cordell Hull in 1946. Hull was still alive at the time; in fact, there are photographs of him posing for artist Bryant Baker.

In 1961, a bust of James K. Polk and another bust of Andrew Jackson were added to the collection. The statues were funded (respectively) by the Polk Memorial Association and the Ladies Hermitage Association. Both were started by sculptor Belle Kinney but finished by Gifford Proctor after Kinney’s death.

This brings us to the controversial Nathan Bedford Forrest statue. Around 1973, Sen. Douglas Henry of Nashville said it was unfair to have a statue of Farragut, who served for the U.S. Navy during the Civil War, but not one of Forrest. “On one side, we already had a bust of Admiral David Farragut, the greatest officer from Tennessee during the Civil War,” Henry said. “So I figured, why not put Forrest, his counterpart, on the other side? I thought it was appropriate that we honor the two outstanding officers of the Confederacy and the Union from Tennessee.”

What is interesting about Henry’s logic is that Maury (whose bust was also in the Capitol at that time) also sided with the Confederacy. In fact, Maury designed mines for the Confederate Navy, which is one reason there is a prominent statue of him in Richmond, Virginia.

In any case, the General Assembly passed a resolution honoring Forrest but didn’t allocate money to build a memorial. The fundraising task fell to the Joseph E. Johnston Camp Number 28 of the Sons of Confederate Veterans, which raised the money for a statue, created by artist Loura Jane Herndon Baxendale.

From the time the bronze bust of Forrest was unveiled in November 1978, it was controversial. “Anything that symbolizes the Confederacy is an obvious insult to blacks,” Kelly Miller Smith, pastor of First Baptist Church, Capitol Hill, said on the day of the unveiling.

By the late 1970s, the fact that there wasn’t a bust of former President Andrew Johnson in the Capitol was a source of amusement. At the initiative of Rep. Joe Bewley of Greeneville, Johnson’s bust went up in 1979. (By the way, Jim Gray’s statue of Johnson on the lawn of the Capitol wasn’t erected until 1995.)

Speaking of Jim Gray, who died only last year, his bust of John Sevier was unveiled in the 1980s and would remain on the second floor of the Capitol until about 10 years ago, when it was moved downstairs.

In the 1990s, a group of activists began asking for the state to do something to acknowledge the 75th anniversary of Tennessee’s passage of the 19th Amendment. Alan LeQuire’s bas-relief sculpture depicting Tennessee’s passage of the suffrage amendment came out of these efforts.

In 2000, the General Assembly allocated money to memorialize African-Americans elected to the General Assembly during Reconstruction. Out of this project came another bas-relief sculpture — this one representing former slaves voting during Reconstruction — as well as the bust of Sampson Keeble by sculptor Jen Huang Powell. When the Keeble bust was unveiled, the Maury statue was moved to the Tennessee State Museum (and no one objected, by the way.)

The most recent addition to the second floor of the State Capitol is the bust of David Crockett, unveiled in 2016. This idea began with Tennessee State Museum curator Jim Hoobler and was pushed through the General Assembly by Sen. Mark Norris and Rep. Gerald McCormick.

This brings us to where we are today — a situation where the hallway between House and Senate chambers contains busts of Jackson, Gleaves, Farragut, Hull, Polk, Johnson, Keeble and Crockett. Thanks to a state law called the Tennessee Heritage Protection Act, none of them can be moved without permission of both the State Capitol Commission and the Tennessee Historical Commission.

For the assistance of everyone who has a say in the matter, here are key points I’d like to make:

- The process under which busts are placed in the Capitol has always been somewhat of a function of party and regional squabbles, which accounts for why Jackson and Polk statues were put up decades before Johnson.

- The Farragut and Gleaves busts are there because of a “Hall of Naval Heroes” that never came to fruition.

- The Forrest statue wasn’t put up until after the civil rights movement, not during Reconstruction (as many people seem to believe). It was unveiled 113 years after the Civil War — apparently because there was already one of Farragut.

- Some of the people enshrined in the Capitol are commonly known by most Tennesseans. However, that is not the case for Albert Gleaves and Sampson Keeble.

- One of the men featured in a bust on the second floor of the Capitol was enshrined while he was still alive (Hull).

- There are no women enshrined on the second floor of the Capitol.

I hope all this research helps the state of Tennessee come to some sort of peaceful resolution about what to do.

Thanks to both Eddie Weeks, librarian for the Tennessee General Assembly, and Tennessee State Museum curator Jim Hoobler for their help researching this matter.