In 1850, about one in five Tennesseans was held against his or her will, forced to live as a slave.

For many years, history books didn’t talk much about these enslaved people. Historians didn’t say much about what their lives were like, how they lived, how they worked and how they were sometimes forced to leave their families.

A few years ago, John Baker of Robertson County began researching his family. In doing so, he did a lot to change how much people know about the institution of slavery.

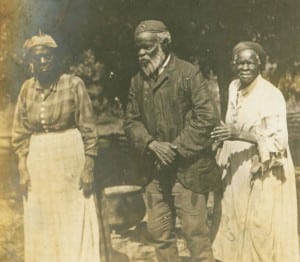

It all started when Baker was a seventh-grader at Westside Elementary School. While paging through his social studies book, he was drawn to a photograph from 1891. The photo showed four older people in front of the Wessyngton mansion in Robertson County.

A few months later, Baker’s grandmother told him that he was related to all four of the people in the photo. “That’s my grandmother and grandfather,” she told him, pointing to the seated couple (which meant they were his great-great-grandparents!).

This revelation inspired the teenage Baker to interview older family members and family friends, some of whom lived nearby. One of them was Mattie Terry, an elderly lady who lived down the street and also had family connections to the Wessyngton Plantation.

Terry told Baker stories that her great-grandmother Sarah (a slave at Wessyngton) had told her years before. These included stories about what the slaves did, how hard they worked and even how they got in trouble for praying.

“Grandma Sarah told us that prayer meetings had to be held in secret on the plantation,” she said. “Slaves put overturned kettles and pots at their doors to muffle the sound of praying and singing.”

The more Baker learned, the more he wanted to know. His interest was fueled by the fact that the Wessyngton mansion was still standing. In fact, the house and much the land around it was still owned by the descendants of its original owners.

Baker learned that Wessyngton wasn’t just any plantation. Consisting of three parts and more than 13,000 acres, it was the largest tobacco plantation in America on the eve of the Civil War. At that time, the owner of Wessyngton, George A. Washington, had 274 slaves.

Baker took a tour of the Wessyngton Plantation and its grounds, which included former slave cabins and a slave cemetery with unmarked graves. He read every book he could find about Robertson County history and about slavery. He started visiting the Tennessee State Library and Archives to study its immense collection of Wessyngton Plantation papers.

You see, in the 1960s, the Washington family donated to the library all the records connected to the history of the house and family. Consisting of 11,200 items, the papers included letters, photographs, newspaper articles, journals, diaries, bills of sale, doctor bills and more.

Baker has since spent a good part of his life researching his family, Wessyngton, the history of Robertson County and slavery. In 2009 Simon & Schuster published his book, “The Washingtons of Wessyngton Plantation: Stories of My Family’s Journey to Freedom.”

This book received national publicity and resulted in news coverage, documentaries and even an exhibit at the Tennessee State Museum in Nashville.

This is certainly of interest to the people who happen to be related to folks who lived at Wessyngton (and there are tens of thousands of them). But Baker’s research has also revealed a lot about what slavery was like and how slavery evolved at Wessyngton:

- When plantation founder Joseph Washington migrated west from Virginia in 1796, he had only two slaves that were classified as taxable. He added to that number over the years through purchase or inheritance and by birth. One of his first slave purchases was in 1802 when he acquired two girls named Sarah and Jenny. The original bill of sale for the two girls is part of the collection at the Tennessee State Library and Archives.

- The slaves at Wessyngton worked in the house and throughout the grounds. They did most of the construction of the main Wessyngton mansion, including making the bricks from clay. They took care of farm animals. They smoked hams and distilled whiskey (both of which the plantation became famous for). But mostly, they planted, cared for and harvested tobacco.

- Male slaves outnumbered female slaves at Wessyngton. Because of this, many of the slaves at Wessyngton had wives who lived in other places and whom they probably visited on weekends and holidays. By law, children born from such unions became the property of the mother’s owner.

- One of the crueler aspects of slavery is how slaves were forced to live with the possibility that at any time other members of their family might be sold and forced to move away from them. Baker only found two instances when slaves were sold away from Wessyngton — once in 1805 and another time in 1855.

- Baker documented 88 instances over the years of what he describes as slave “rebellion” — including quarrelling, theft, disturbances, refusal to work and runaways. In fact, the book documents 11 times between 1838 and 1860 when slaves tried to escape. Not one of these slaves made it to free territory; all were returned to the plantation.

- In Middle Tennessee, there were instances where slaveowners granted freedom to some of their slaves. However, “there is no record that the Washingtons ever granted any slave his or her freedom,” Baker’s book says. For the slaves at the Wessyngton plantation, emancipation came during the Civil War. At that time, many of the former slaves left the area. But according to Baker’s research, nearly 100 of the former slaves remained in Robertson County to work as sharecroppers.

In the process of his research, Baker learned the names and birth and death dates of 445 people who were enslaved at Wessyngton. About 200 of them are buried at Wessyngton — the vast majority of them in unmarked graves.

With the help of ground-penetrating radar, the remains of more than 200 bodies in the ground at the Wessyngton cemetery were located. And in October 2015, a new monument with the names of all the people who were enslaved there, known to be buried there and assumed buried there was unveiled. It is a remarkable tribute to 40 years of work by John Baker — work that began from a photograph in a social studies textbook.