Millions of Americans have followed in the steps of the Little River Lumber Company without realizing it.

Before the national park was there, a large part of the Tennessee side of the Great Smoky Mountains was owned by the Little River Lumber Company. Between 1901 and 1939, this company cut down hundreds of thousands of trees in the Smokies, turning a forest full of massive trees into a barren landscape.

In the 80 years since, the trees have grown back, and wildlife has returned. But we cannot even begin to imagine what this part of the Smokies looked like when it was a “virgin” forest.

To tell this remarkable story, we have to explain a few things about the history of the logging industry.

In 1900, the England-Walton Company of Philadelphia decided to build a tannery in a remote part of Blount County called Walland. (A tannery is where animal skins are boiled with tree bark and turned into leather, which is used in clothing.) This company invited W.B. Townsend, who was already in the lumber business, down to Tennessee to explore the land for timber possibilities.

As he explored the area, Townsend realized that there was a lot of money to be made harvesting trees in the nearby Smoky Mountains. This lumber could be sold to other companies that built houses, furniture and other things.

Townsend and his partners started the Little River Lumber Company. Before long, it had purchased 80,000 acres of land, was building a sawmill and was working on plans for a railroad to deliver logs from the mountains to the mill.

People were so excited that they named the town around the mill after Townsend!

The lumber business (also known as the “harvesting of trees”) comes up throughout Tennessee history. In areas with a less challenging terrain, it consisted of a few simple steps: You cut a tree down, you lop off its branches, you drag it by mule to the nearest river, you latch it to other tree trunks into a raft and you float it downstream to a sawmill.

All of Tennessee’s large cities had big lumber industries at one time or another. Before cotton took over, lumber was the biggest business in Memphis. For generations, log rafts were a regular sight on the Cumberland River in Nashville.

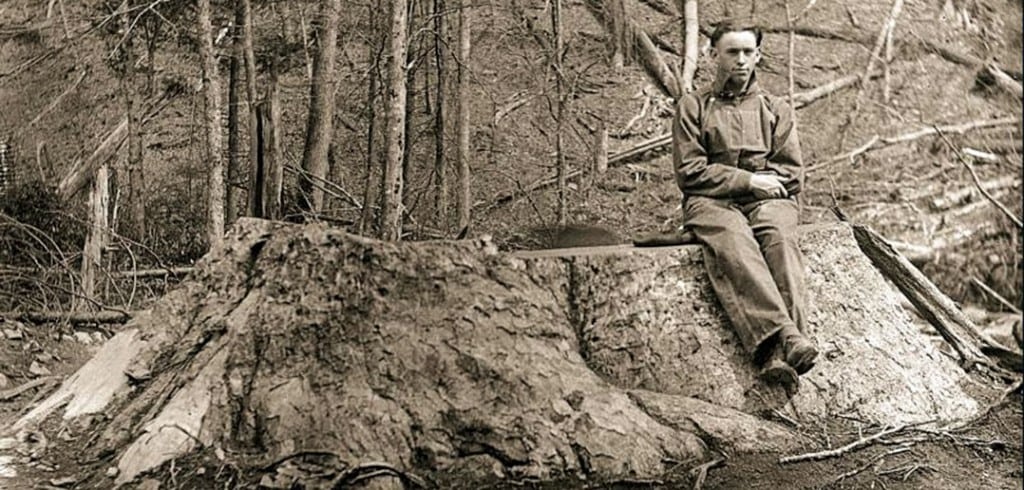

In 1900, there were thousands of enormous trees in the Great Smoky Mountains. There were poplar, ash, chestnut, oak and maple trees in the Smokies as large as 10 feet or more in diameter. The reason that most of the trees in the Great Smoky Mountains had not been “harvested” prior to this time was because the land was so steep and the rivers weren’t big enough to float huge tree trunks downstream.

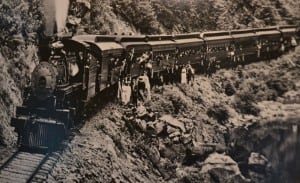

Starting about 1900, the Little River Lumber Company began creating a rail line that started in Walland and went into the mountains, following the course of the Little River and its main tributaries. These tributaries, which can be seen on any map today, have names such as West Fork, East Fork, Middle Prong and Jakes Creek.

The creation of this rail line alone was a difficult task as much of it had to be blasted through solid rock. As the company did this, it pushed a lot of these rocks into the Little River. Today, we don’t really know how many of the boulders in the river were put there by nature and how many of them were put there when the railroad bed was created.

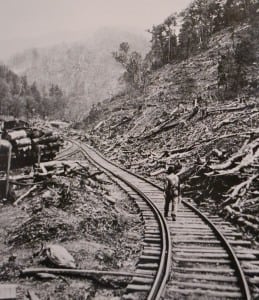

The harvesting of trees began as the rail line was still being created.

Most of the trees were cut down the old-fashioned way — by two men called sawyers working together with a hand saw. This process was physically demanding as well as dangerous as one can never tell for certain in what direction a tree will fall.

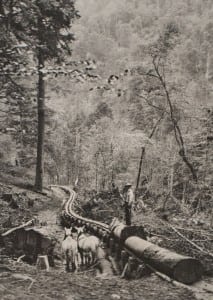

Once the tree had been cut down and the branches cut off, the tree trunk had to be dragged to the nearest rail line. This process was known as skidding. In areas where the terrain was steep, workers would create a skid road — a long, wooden path along which a log would be slid down the mountainside with the help of a mule. Once the logs had been dragged to the railroad, they were lifted and placed on a rail car by a steam-powered log-loader.

Workers toiled long hours and lived with their families in communities built and owned by the Little River Lumber Company. Of these communities, the two best-known were Elkmont and Tremont.

Like coal miners in other parts of Tennessee, workers for the Little River Lumber Company bought their groceries, rented their homes and even paid their electric bills to their employer. They worked six days a week, usually taking Sunday off, going to church in the morning and taking a free train ride to Townsend in the afternoon.

Working for the Little River Lumber Company may sound like a rough life by today’s standards. However, the people who worked for the company didn’t necessarily see it that way. “The logging operation was a blessing for the mountain people who were given the opportunity to have jobs and earn a living,” says Sandy Headrick, a board member of the Little River Railroad and Lumber Company Museum in Townsend. “Colonel Townsend was well liked and respected for all he did for the workers in terms of jobs, pay, healthcare and the quality of life that came with the community.”

Working for the Little River Lumber Company may sound like a rough life by today’s standards. However, the people who worked for the company didn’t necessarily see it that way. “The logging operation was a blessing for the mountain people who were given the opportunity to have jobs and earn a living,” says Sandy Headrick, a board member of the Little River Railroad and Lumber Company Museum in Townsend. “Colonel Townsend was well liked and respected for all he did for the workers in terms of jobs, pay, healthcare and the quality of life that came with the community.”

Many loggers’ families lived in portable houses that were moved by train to different areas where trees were being harvested. These houses were located right on the train tracks because the terrain was so steep and because the log-loader couldn’t reach very far from the train tracks.

“The railroad tracks were in front of our house, and the river was in back,” recalls Gladys Oliver Burns, whose father worked for the Little River Lumber Company. “We were really in a dangerous situation, but we didn’t realize that; we didn’t know.

“We were happy, actually. We had a happy life.”

These mobile communities of portable houses became known as stringtowns, and they were located at various places in the Great Smoky Mountains.

Always on the lookout for a new way to make money, in 1911 the Little River Lumber Company developed a hotel in Elkmont known as the Wonderland Hotel. The company used its railroad to take tourists, hunters and fishermen from Knoxville and other locations to the hotel. These day-long and weekend-long excursions gave many people their first experiences in the Great Smoky Mountains.

The Little River Lumber Company clear-cut almost all the land drained by the Little River, which is most of the Tennessee side of the Great Smoky Mountains. W.B. Townsend’s company laid 150 miles of train track, cleared about 75,000 acres of land and cut 560 million board feet of lumber.

It did so at a time when many activists such as Knoxville residents Willis and Anne Davis and North Carolina resident Horace Kephart were trying to preserve the Smokies and have the area turned into a national park.

In 1924, the Little River Lumber Company agreed to sell its 75,000 acres in the Great Smoky Mountains to the state of Tennessee as part of the process under which the national park was formed. As part of that deal, the company reserved the right to log a portion of it for 15 more years.

By the time the Little River Lumber Company and other logging businesses were moved out, about two-thirds of the national park had been clear-cut.

W.B. Townsend died in 1936. By that time, thousands of workers with the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) had begun the process of building roads on the railroad beds created by the Little River Lumber Company. Once that job was completed, CCC workers created new trails in the Smokies — many of them also on former railroad beds.

It took many years, but the trees have grown back in the Smoky Mountains. However, “The magnificent forest we see today is a pale shadow of the immense original natural blanket which spread before pioneer settlers when they came to farm in ever-increasing numbers in the early days of the nineteenth century,” says a book about the Little River Lumber Company called “Whistle over the Mountain.”

Because of logging and hunting, the population of animals such as bear, deer and hawks in the mountains fell to almost nothing in the 1930s. However, it has recovered now to a point that hikers frequently encounter animals such as black bears in the park.

The Wonderland Hotel remained at Elkmont until the 1990s, when the National Park Service closed it. Today, Elkmont is the largest campground in the Great Smoky Mountains National Park.

Tremont is now used as an educational institute where thousands of students from across the country come for overnight retreats.

The best way to learn more about this incredible saga is to visit the Little River Railroad and Lumber Company Museum in Townsend.