From a column originally penned for “Comet Earthquake and Fire Canoe” — Tennessee History for Kids’ new fourth-grade reading booklet.

You can talk about the battles of Bunker Hill, Saratoga and Kings Mountain all you want, but more Americans died on British prison ships than in all the battles of the Revolutionary War combined.

Prisoners are a problem in every war. Since the British won most of the battles in the Revolutionary War, especially early on, the British had a lot of American prisoners.

When the war started, the British had humane procedures for handling prisoners captured in wars with foreign countries. They chose not to follow those procedures because King George III declared the rebelling Americans to be traitors, not foreigners.

To make sure American prisoners didn’t escape, the British turned some old ships into prisons. Most were located off the coast of New York, but there were also prison ships in Philadelphia; Charleston, South Carolina; and St. Augustine, Florida.

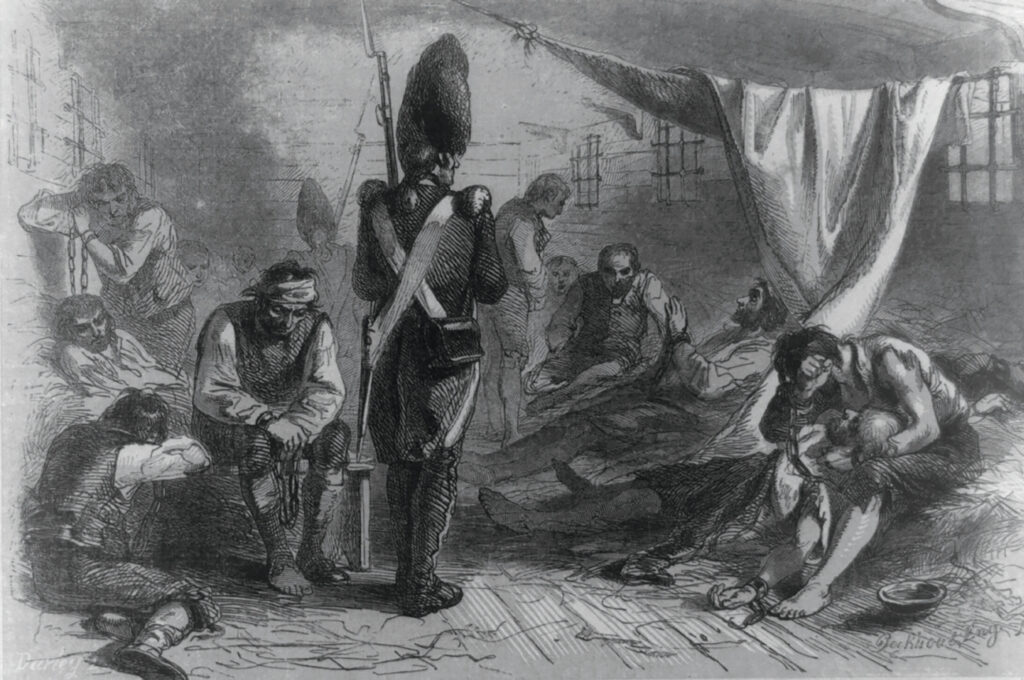

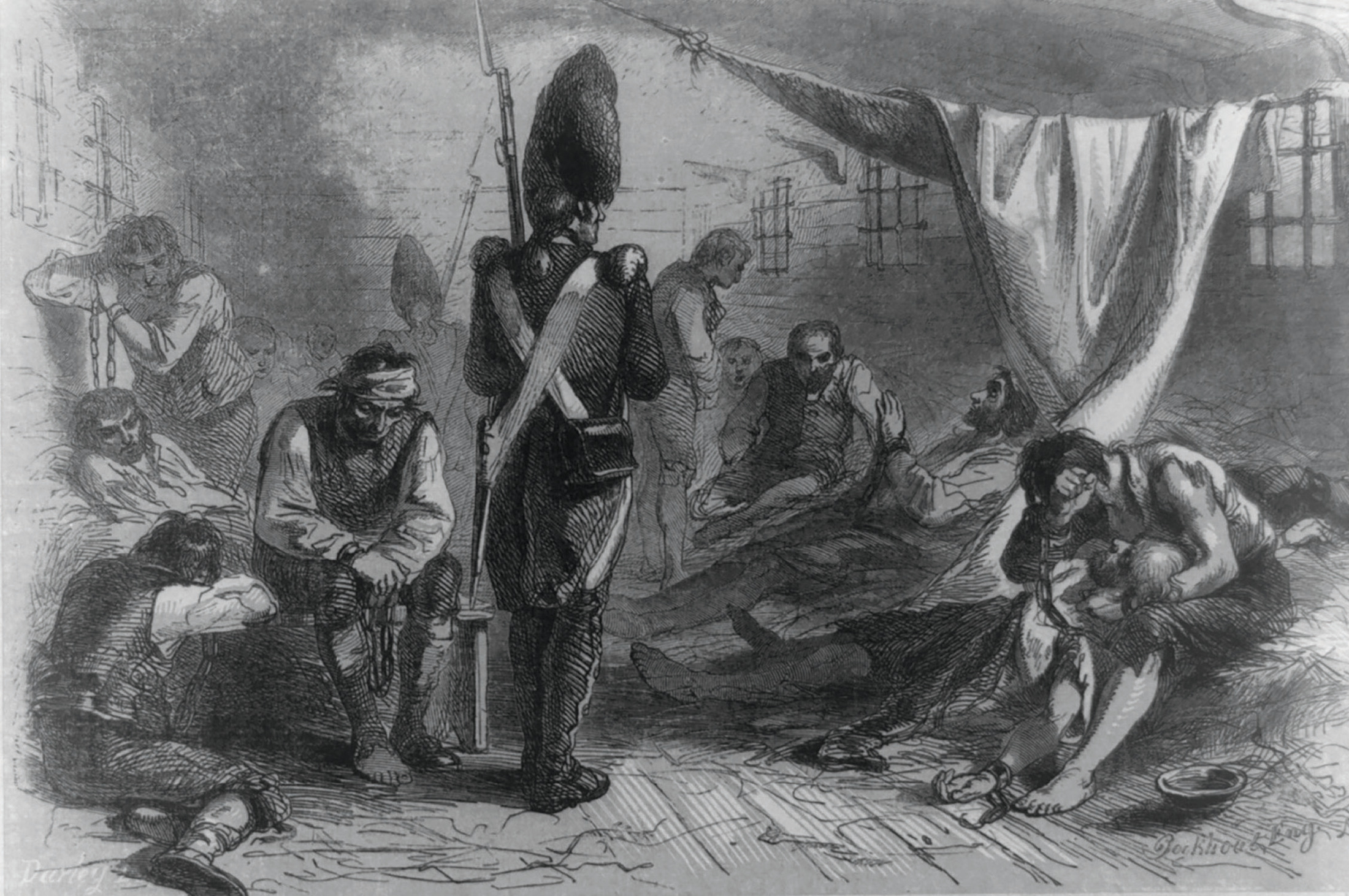

Conditions on these ships were appalling. Captured soldiers and sailors were chained up, packed in, fed very little and given little, if any, medical care. Disease was rampant, and thousands of men died of smallpox or cholera.

You might ask why the soldiers didn’t jump overboard and try to swim to shore and escape. Many of them couldn’t swim; others were too weak to try. Most who did attempt escape died trying. In October 1781, six prisoners tried to escape from one of the prison ships in New York. Four were either shot or drowned; one was bayoneted by a guard and died the next day; the sixth realized he had no chance to survive and climbed back up the anchor chain to the ship.

One of the few soldiers who did manage to escape from a prison ship was Robert Sheffield. When he got home, Sheffield wrote a detailed account of his experiences that was published in several American newspapers in the summer of 1778. Sheffield said prisoners were chained up naked and that the air was foul and the conditions so dark that it was often days until a dead body was discovered.

An excerpt:

“Their (the prisoners’) sickly countenances and ghastly looks were truly horrible; some sweating and blaspheming; some crying, praying and wringing their hands, and stalking about like ghosts and apparitions; other delirious and void of reason, raving and storming, some groaning and dying — all panting for breath, some dead and corrupting.”

Sheffield’s account was so horrifying, in fact, that it might have convinced a lot of colonists who were still “on the fence” about the Revolution to turn against the king.

The British had a policy under which prisoners could earn their freedom if they agreed to switch sides in the war and take up arms against the rebellious colonists. We now know that very few of the prisoners did this, which means thousands of men chose death over joining the British. “They preferred to linger and die rather than desert their country’s cause,” Thomas Dring, one of the American prisoners, said of his colleagues.

The most infamous of the prison ships was the HMS Jersey, which was anchored off the coast of New York. About 1,400 men were imprisoned on the Jersey at one time, but it is estimated that the number of prisoners who spent time on that ship was several times that number because so many of them died.

In fact, about eight American prisoners died every day on the Jersey.

And what happened to their bodies? Some were thrown overboard, but most were taken to a nearby shoreline and buried in shallow graves. After the war, what was left of these bodies was exposed, and people who lived in Brooklyn found hundreds of bones and body parts along or near the shore. Some of these human remains now lie under the Prison Ship Martyrs Monument in Fort Greene Park — probably the most overlooked Revolutionary War site in United States.

Prison ships also had an important effect on Tennessee’s history. During the war, the British sometimes allowed volunteer doctors and nurses to go on board prison ships to treat the sick and wounded. One American woman who did this was Elizabeth Jackson, who traveled all the way from her home in the hills of North Carolina to nurse prisoners on a ship in Charleston. Jackson caught cholera and died, leaving her 14-year-old son, Andrew, orphaned.

With nothing to keep him in North Carolina, Andrew Jackson moved — first across the mountains to Jonesborough and Greeneville, Tennessee, and eventually all the way to Nashville. Jackson became a lawyer, a judge, a soldier and a general. He got revenge on the British on Jan. 8, 1815, at a battlefield near New Orleans called Chalmette.

Today, we estimate that about 7,000 Americans were killed in battle during the Revolutionary War, and as many as 14,000 died on British prison ships.

All of this reminds me of a trip I once took to Philadelphia. It was a beautiful day, and I managed to fit in tours of Independence Hall, Betsy Ross’ home and the new Constitution Center. However, the stop that made the biggest impression on me was the Tomb of the Unknown Revolutionary War Soldier in Washington Square. There’s a statue of the first president there, but it isn’t the statue itself that jumped out at me; it was the words in granite behind it.

“Freedom is a light,” the inscription says, “for which many men have died in darkness.”