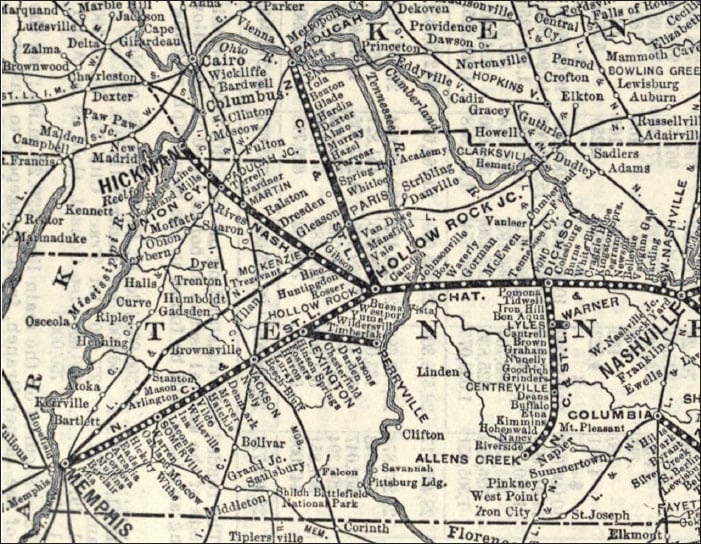

If you scan the 1903 map of the Nashville, Chattanooga and St. Louis Railway system, the name “Hollow Rock” jumps right out at you.

The NC&St.L, as the rail was abbreviated, did more to develop the modern economy of Middle and West Tennessee in the late 1800s than any other railroad. Its main line intersected with branch lines at towns such as Dickson, Cowan, Decherd and Bridgeport, Alabama. It carried coal, timber, cotton and passengers to and from locations such as Memphis, Monterey, McMinnville and Pikeville.

None of this seems too surprising. But this may: Between about 1880 and 1930, there was only one place in the NC&St.L where four lines intersected. It wasn’t Nashville or Chattanooga. It was the Carroll County community of Hollow Rock.

Hollow Rock is where the main line from Nashville split into three branch lines — one to Memphis, one to Hickman, Kentucky, and one to Paducah, Kentucky.

Because of this, Hollow Rock was a pretty important place.

In the 1890s, the NC&St.L moved its operation a few hundred feet from Hollow Rock to a new town it created from scratch. The railway bought land and built a larger yard, passenger station, train shed, offices, company hotel and a roundhouse for engine maintenance and repair. The company oversaw the design and development of a town where engineers, mechanics, firemen and other employees could live, shop, go to church and send their kids to school. The NC&St.L named it Junction City, then later renamed it Bruceton.

“I’ve always heard that the reason they changed the name from Junction City is that there was confusion with the name Johnson City,” says Buddy Smothers, a retired high school history teacher and basketball coach who grew up there. “They renamed it for a railroad executive named W.P. Bruce.”

Bruceton’s wooden roundhouse burned shortly after it was put to use and was replaced by one made of steel and reinforced concrete. You can still see it just off U.S. Highway 70 in the now rather quiet town of Bruceton. Decades after its last use, the old roundhouse keeps out most of the rain. But it is being invaded by weeds, poison ivy and birds that nest in its rafters. At this point, it seems likely that it will one day fall down or be torn down.“It’s sad to see the building like this,” says Smothers. “This used to be the hub of this whole area.”

Bruceton was also a name recognized by just about everyone who rode the railroad. According to “Next Stop on Grandpa’s Road: The History and Architecture of NC&St.L Railway Depots and Terminals,” trains from all four lines of the railroad used to converge at Bruceton at about 11:25 every day.

“If you were lucky enough to have been in Bruceton during the first quarter of the twentieth century, you would have been able to see four trains enter the station and grind to a halt on parallel tracks next to the covered train platform,” the book by Terry Coats states. “For about five minutes, these four trains sat side by side. Passengers alighting from one train, hurrying to pass to one of the three sister accommodations made the Bruceton platforms a beehive of activity. Baggage carts filled with mail and express would weave in and out between the passengers as their drivers hurried to transfer their cargo to the correct RPO (railroad post office).”

The NC&St.L never turned Hollow Rock or Bruceton into large cities. But it did help create enough commerce to maintain a healthy small-town economy with banks, grocery and drug stores, a corn and wheat mill and (eventually) a movie theater.

The NC&St.L was also the foundation of many cultural aspects of life. Kids grew up wanting to work for the railroad and assuming they would one day work for it. The sound of trains coming and going indicated the time of day, every day. Everyone who went off to war and came back did so on the railroad. The NC&St.L used to organize a passenger train — the “Tiger Special” — that would take the high school football team and its fans to road games.

After the NC&St.L merged into the Louisville & Nashville Railroad in 1957, many of the railroad jobs went away. By that time, Bruceton/Hollow Rock had leveraged rail connections to recruit an apparel plant owned by New York-based Henry I. Siegel. At one time, that jeans factory employed 1,700 workers. However, Siegel shut down its operations between 1995 and 2000, which is why there are more vacant commercial buildings in Hollow Rock and Bruceton than there are occupied ones.

“The towns have been losing population for several years now,” says Smothers. “This part of Carroll County really needs jobs.

“And, yes, it would be great to see something done about this old roundhouse. But it’s hard to imagine something happening to it unless something first happens to the town.”

Today, CSX Railroad still has a small operation in Bruceton, and monuments to the town’s railroad roots remain. A few blocks from the old roundhouse, the walls of Bruceton’s city hall are covered with articles and photographs from the town’s heyday as a major railroad intersection. A small civic park nearby features an old caboose and historic marker with the number 95 on it.

“From here we are exactly 95 miles to Nashville,” Smothers says.