If you read this column regularly, you might remember that in September 2014, I started off with my opinion that “the influenza epidemic of 1918 is the most overlooked event in American history” since it killed three times the number of people who died in World War I.

I believed then — and now — that history books seriously underrate the impact of pandemics. Smallpox wiped out half of the Cherokee Nation in 1738–1739. It nearly destroyed George Washington’s Continental Army, which is why he ordered his soldiers to be inoculated. Yellow fever killed about 5,000 of the 25,000 people who remained in Memphis during its 1878 epidemic.

And, of course, future generations will have to make sense of the COVID outbreak of 2020 to 2022. Good luck, future generations.

Until recently, the only thing I knew about cholera outbreaks in the mid-19th century is that one killed James K. Polk. But a few months ago, I made a disturbing discovery about a cholera outbreak among the workers who built the Nashville and Chattanooga Railroad tunnel and their families.

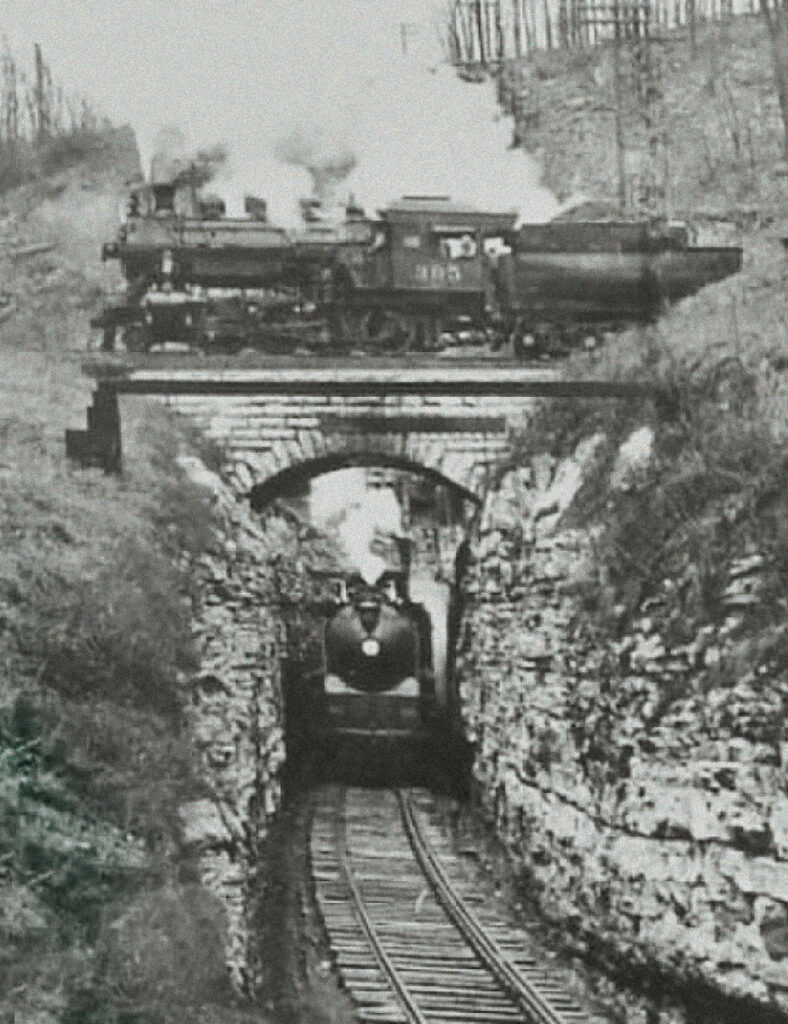

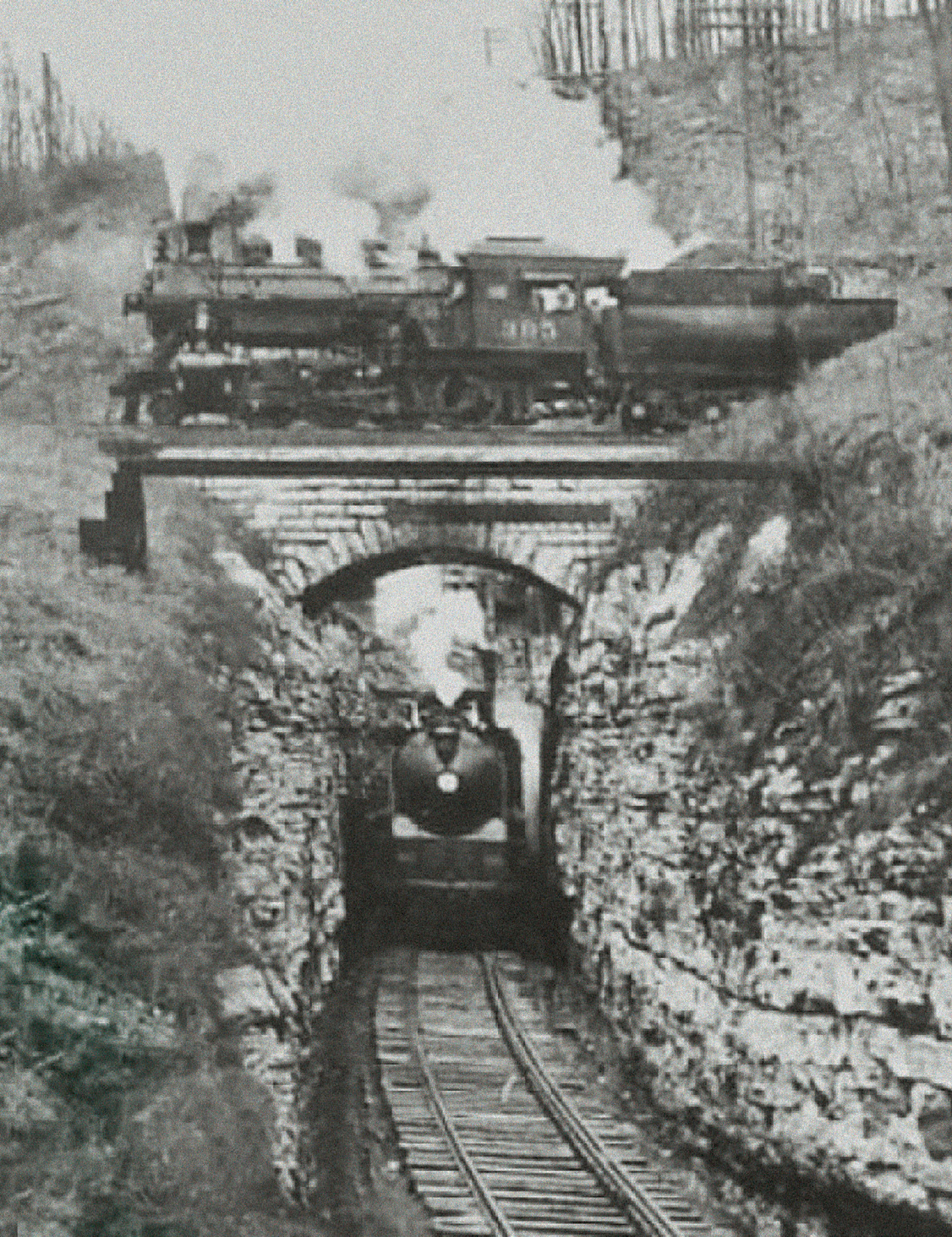

First, some background: The Nashville and Chattanooga was one of the first railroads built in Tennessee. When it started operation in 1854, it connected Nashville to the Tennessee River, Atlanta and Savannah, Georgia — reducing travel time from Nashville to the Atlantic Ocean from about a week to about a day.

However, the N&C wasn’t an easy railroad to build. The most challenging part was crossing the Cumberland Plateau — a feat that required the blasting of a 2,200-foot tunnel near the Franklin County community of Cowan.

There continues to be some uncertainty about the ethnic status of all the people employed to build this tunnel and the stretches of railroad near it. I maintain that some of them were enslaved. But Tom Knowles, a local historian on the board of the Cowan Railroad Museum, says the vast majority of tunnel workers were Irish. “Slaves were hired to build the tunnel at first, but one of them died,” Knowles says. “As a result of that death, the contractor was ordered by the courts to pay $1,200 for ‘loss of property,’ a huge sum of money at that time. Meanwhile, there was a steady stream of Irishmen available who carried no such liability. So Irish and others completed the tunnel.”

To add to the confusion about enslaved workers, different stretches of the Nashville and Chattanooga were built by different contractors. The stretch of railroad between the Tennessee River and Chattanooga was built by the firm Murdoch and Townsend, which bought newspaper ads that prove it hired as many as 1,000 Irish workmen and 500 slaves.

In 1849 and 1850, there were cholera outbreaks all over the United States. The death counts were especially bad in Mississippi River cities such as New Orleans and St. Louis, but it was also awful in Nashville where an estimated 311 people died from the disease. The most famous of the casualties was former President James K. Polk, who died on April 2, 1849.

Cholera spread among railroad laborers working on the Nashville and Chattanooga Railroad tunnel just south of Cowan on July 16, 1850. According to a story in the Winchester Independent, the first victim was a woman named Mrs. Mills, who died about a day after she fell ill. The second death was Edward Paul, a native of Cornwall, England, and one of the superintendents on the tunnel construction. “He was a married man, and he expected his wife here from Pennsylvania in today’s stage,” the newspaper reported. By the time this small item went to press, six other people died of cholera, including one child.

Today, we don’t know whether printed accounts of this outbreak are exaggerated or understated. We do know, however, that what the Winchester Independent reported on July 26 is horrible to contemplate: “At the beginning of the cholera, the hands and families living at the tunnel were dispersed and scattered in every direction, there was no security in flight; the fell (cruel) disease followed them up and cut them down wherever they went.”

On Aug. 2, the Independent listed the names of 28 people near the tunnel who died of the disease, including four enslaved people and six children. However, the newspaper maintained that the town of Winchester (about seven miles away) had escaped the scourge. It made no mention of law enforcement efforts that the town had made to keep diseased workers away, although there is no doubt that there would have been some.

Only a few weeks later, the (Nashville) Republican Banner sent a reporter to Cowan. That reporter said that “a number” of cabins had been burned in the communities where workers lived because it was common practice to burn down the cabins of people who died of cholera — often with their bodies still in it. The reporter also said that 31 workers had died of cholera “out of a population of one hundred and eighty.”

All of this reminded me that there is an abandoned Irish cemetery along the railroad tracks above Cowan. I’ve never seen it (it is difficult to reach and on private property), but oral history maintains there are many unmarked graves of cholera victims there.

Only a few months later, in February 1851, the tunnel was completed. There was a big ceremony and celebration; some people walked through the tunnel carrying candles while others got to ride through it on a train car that was pulled by a horse. That event was reported in newspapers as far away as Buffalo, New York, and the word “cholera” appeared in none of those articles. The railroad, and the state, had moved on.