Parents love to take their kids to play in the fountains at Bicentennial Capitol Mall State Park in Nashville. I’m not sure if the kids or parents notice this, but the fountains represent Tennessee’s rivers. There are fountains named for large rivers like the Mississippi and Tennessee and smaller waters such as the Obion and Harpeth.

You won’t find a fountain representing the Conasauga River at the Bicentennial Mall, however. It is as if the river doesn’t exist. But there was a time when the Conasauga was considered quite valuable.

The Conasauga River flows west through Polk County in southeast Tennessee. It crosses under Highway 411, dips into Bradley County and turns south into Georgia. From there it continues past Dalton and merges into the Oostanaula River. The Oostanaula flows into Alabama, merges into the Coosa River and after hundreds of twists and turns makes its way to the Gulf of Mexico.

In fact, the Conasauga River is the only river in Tennessee that is not part of the Mississippi, Tennessee or Cumberland River systems. Though today this may sound like trivia, it made the Conasauga quite alluring in the early 1800s.

Before the Tennessee Valley Authority existed, there were serious barriers to navigation on the Tennessee River. Downstream from present-day Chattanooga was a series of rapids, shoals and currents with names like the Suck, Frying Pan and Boiling Pot. A hundred miles or so downstream, there was an even more notorious series of barriers collectively known as the Muscle Shoals. There, the river widened to as much as a mile and a half and got so shallow that boats could get stuck for days at a time.

While all of this may make the Tennessee river sound like a kayakers paradise, the boatmen who transported goods along the river by flatboat and keelboat didn’t see it that way.

The barriers to navigation along the Tennessee River were so bad that they retarded the commercial growth of East Tennessee. In 1830, the top 10 counties in Tennessee (population-wise) were all in Middle Tennessee (West Tennessee was just beginning to be developed). Counties such as Davidson, Sumner, Williamson and Wilson had far more people than Knox and Blount because they had easy access to the more dependable Cumberland River.

East Tennessee merchants and boatmen were constantly looking for alternatives to the long, bumpy and dangerous trek down the Tennessee River, all the way to the Ohio and Mississippi rivers and down to New Orleans. In 1821, some keelboat operators tried something different. They began taking the Tennessee River downstream to the Hiwassee River, then the Hiwassee up-stream to the Ocoee, then the Ocoee upstream to a point about five miles south of present-day Benton. Boats and cargo were then lifted onto big wagons and dragged by oxen nine miles south, where they were lowered onto the Conasauga for the long journey to Mobile Bay.

Both ends of this portage were on Cherokee land. The portage on the Ocoee side was owned and operated by a Cherokee family named Hildebrand, while the portage at the Conasauga end was operated by the Mc-Nair family.

Today you can still find a road named for the Hildebrand family on the north end of the route and the tiny McNair family cemetery on the south end. The ninemile stretch between these two take-out points still exists in the southwest part of Polk County — known locally as the Old Federal Road.

For about a generation, products such as flour and whiskey were moved with regularity through the portage. The route, though an interesting alternative, was not efficient enough from a commercial point of view. No sooner did it start becoming used than talk began of a canal connecting the Ocoee and Conasauga rivers.

Today, the notion of this canal might seem hard to believe. But the 1820s was America’s “canal era.” The 336mile Erie Canal connecting the Great Lakes to New York City and the Atlantic Ocean was being built in the early 1820s, and many other less-prominent canals were being developed as well. Commercial boats (keelboats, in particular) were much, much smaller than they are now. And any canal would have made water navigation feasible through a series of locks.

In 1826, the Tennessee General Assembly granted a charter to the Hiwassee Canal Company, whose intent was to develop the canal. About that time, Tennessee Gov. Joseph McMinn petitioned Congress to obtain the permission of the Cherokee Nation to build the canal.

The U.S. War Department sent two men, one of whom was a West Point-trained civil engineer, to survey a potential canal. The men determined that the route was “feasible” and said 15 locks would need to be created — 10 on the Ocoee side and five on the Conasauga.

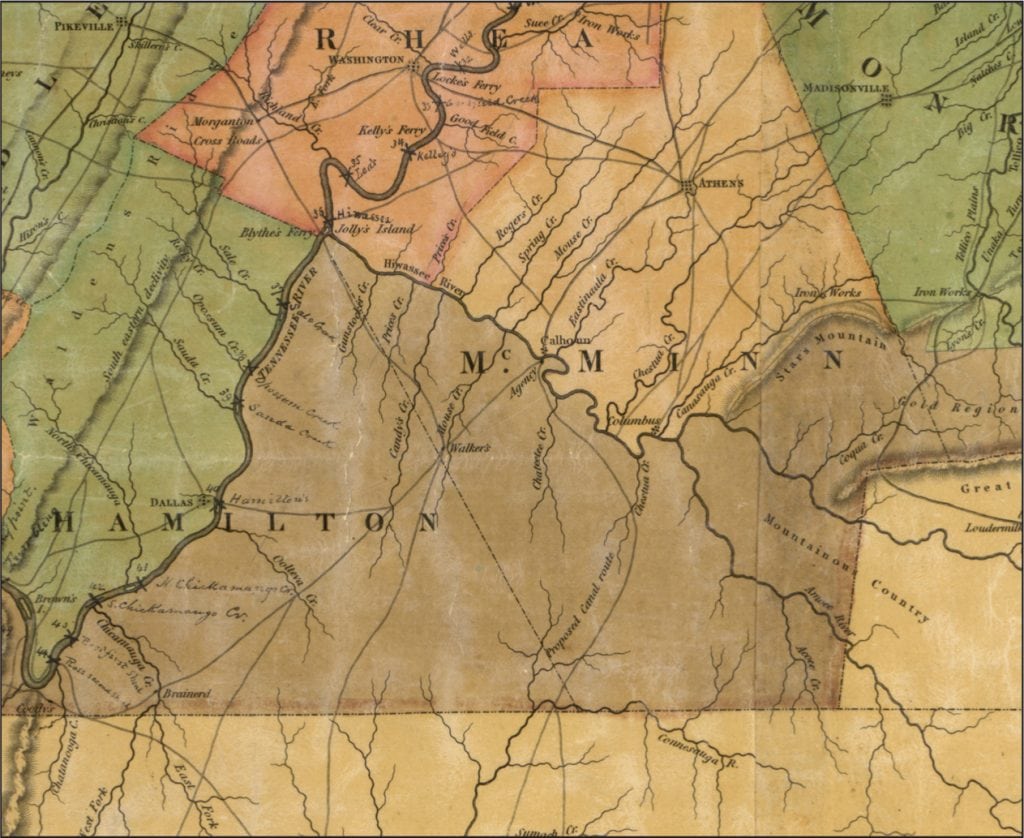

It was about this time that Matthew Rhea’s landmark map of Tennessee came out with the words “Proposed Canal Route” between the Hiwassee and the Conasauga rivers.

Had the Ocoee-Conasauga canal been built, Tennessee history might have turned out differently. East Tennessee might have grown a lot more prior to the Civil War. Bradley and Polk counties might have larger cities today.

However, the canal was never built. One reason may have been President Andrew Jackson’s lack of enthusiasm for internal improvements subsidized by the federal government. But the main reason appears to have been the opposition of the Cherokee Nation to the canal. It was, after all, Cherokee land at the time. When asked to sell the land through which the canal would be dug, Cherokee chiefs rejected the notion outright.

“Your propositions to purchase from us a tract of land … as would be necessary for a canal to connect the Hiwassee and Connasaga with each other were received,” read a letter signed by 44 Cherokee chiefs (including John Ross) on Oct. 11, 1827. “The representatives of this nation solemnly pledged themselves in General Council that they would never dispose of one foot more of land again.”

During the 1830s, matters related to the Cherokee were centered on the Indian Removal Act and the tragic Trail of Tears that followed. By the time the Cherokee left, railroads had begun to take over America. (Remember that the first railroad west of the Appalachians was created in Tuscumbia, Alabama, as a shortcut around the Muscle Shoals.) In any case, the Ocoee-Conasauga canal was never dug.

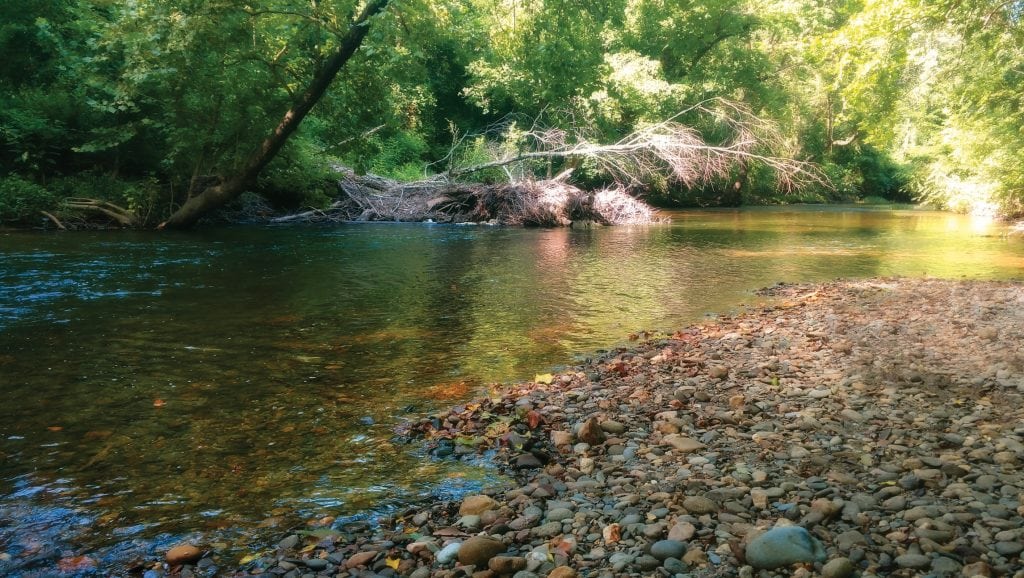

Today, the Ocoee is known for whitewater rafting. The Conasauga River, though little known to most Tennesseans, is notable for the biodiversity of its fish, mussel, snail and crayfish populations. In fact, the Conasauga has at least 10 species of fish and mussels listed as endangered and threatened — and many of them might be gone by now had the isolated Conasauga system been connected to the Tennessee River system. So it is just as well that the Ocoee-Conasauga canal was never built.