I spent a good part of last summer and fall searching for old photographs to be included in the Tennessee History for Kids booklets.

I spent many long nights staring at a computer screen that showed images from the Tennessee State Library and Archives, the Library of Congress, the International Museum of Photography and Film and other organizations.

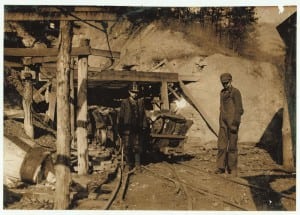

I was mesmerized by photographs of child laborers taken in the early 20th century and learned that many of these pictures were taken by Lewis Wickes Hine.

Hine was the photographer for the National Child Labor Committee (NCLC) from 1908 until 1912. The NCLC, a private organization, had been started by people concerned with the plight of working children.

Hine traveled through the eastern United States, taking photographs of child laborers at sweatshops in New York, apparel factories in North Carolina and coal mines in West Virginia.

Hine also visited Tennessee, capturing images at the May Hosiery Mill in Nashville, the Brookside Mills in Knoxville, the Elk Cotton Mills in Fayetteville and places in between.

It may be our impression that Tennessee’s children were learning their ABCs in one-room schoolhouses in 1910. Hine’s photographs prove that thousands of kids were doing nothing of the kind.

“If I could tell the story in words,” he used to say, “I wouldn’t need to lug around a camera.”

Hine took notes about the children he photographed and the conditions in which they worked. “These all work in Cleveland Hosiery Mills,” he wrote about one group of girls he photographed in Tennessee. “The very youngest one (with curls) said, ‘I ravels and pick up.’ Small boy in another mill said, ‘Over in Cleveland, they work ’em so little, they have to stand ’em on boxes to reach.’”

There is no doubt that Lewis Hine’s photos led to the passage and imposition of child labor laws across the United States. “His photographs would awaken the consciousness of the nation and change the reality of life for millions of impoverished, undereducated children,” the National Child Labor Committee website says today.

Hine may have done wonders to raise the fortunes of American children, but he wasn’t able to secure a comfortable retirement for himself. Unable to find work for most of the 1930s, he died destitute in 1940.

Today, Tennessee’s children spend seven hours a day in school rather than 12 hours a day working in cotton mills. So much has changed in the last 100 years, in fact, that it is almost hard for us to imagine the state Hine captured on film.

For more on Lewis Hine and his photographs, read “Kids at Work: Lewis Hine and the Crusade Against Child Labor” by Russell Freedman.