The real story of why Tennessee rewrote its sacred document in 1870

There aren’t many Tennessee laws that address social studies standards. One of the few that does requires teachers to explain that Tennessee has had three different constitutions and how changes have been made to the Tennessee Constitution of 1870 in the last century and a half. Using legal terminology, the law is Tennessee Code Annotated 49-6-1028.

To be honest, I didn’t feel like I knew this topic well, so I researched it. Some of what I discovered came as a surprise.

First of all, I suspect most people don’t know why Tennessee had the 1870 Constitutional Convention in the first place. Yes, it had something to do with the Civil War. However, Tennessee outlawed slavery and passed the 13th Amendment in 1865 and was readmitted to the Union in 1866. The federal government didn’t require Tennessee to rewrite its constitution because of the war.

According to Lewis Laska’s book “The Tennessee Constitution,” the way the state was governed in the years during and immediately after the Civil War convinced most Tennesseans that a new constitution was necessary. Tennessee’s chief executive from 1862 to 1865 was military governor Andrew Johnson; his successor was the even more unpopular William Brownlow. More than any other governor in the state’s history, Brownlow ran Tennessee like it was a dictatorship. “The Brownlow regime brought a period of vengefulness, incompetence and corruption to the state,” Laska writes. “Brownlow used the militia as a tool of oppression, suspended the writ of habeas corpus, mismanaged the state’s finances and saddled the state with debt.”

Perhaps the most controversial thing Johnson and Brownlow did was to require everyone to swear to a 161-word oath in order to vote. Not only did the oath force the prospective voter to swear that he was an “active friend of the government of the United States,” it also required him to say that he “sincerely rejoice(s) in the triumph of its armies and navies in the defeat and overthrow of the so-called Confederate States.”

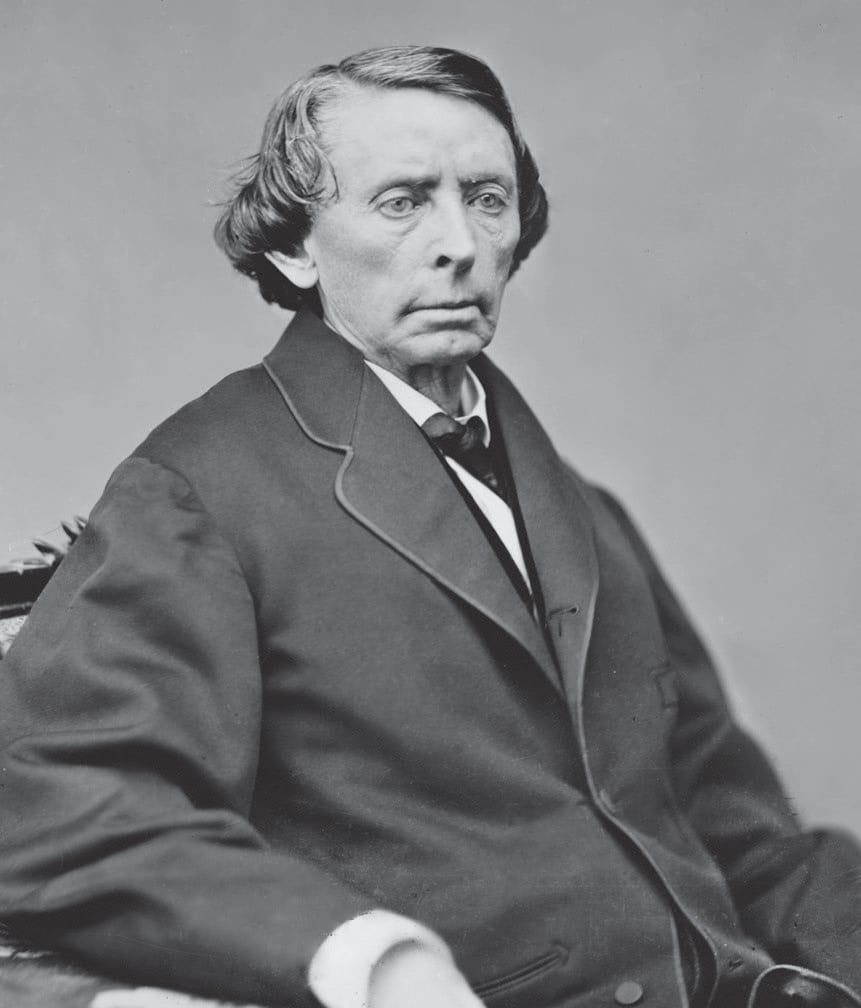

The term of William Brownlow as governor convinced many Tennesseans that the state needed a new constitution (Mathew Brady photo/Library of Congress).

This requirement, Laska points out, “meant that only Union loyalists and liars” could vote in Tennessee in the mid-to late 1860s. In 1865, for instance, only 21,144 Tennesseans cast ballots in the statewide referendum over slavery — about one-seventh the turnout in the 1860 presidential race.

By the time Brownlow left office in 1869, many people regarded as invalid just about anything state government had done in the previous first few years following the war.

In 1869, under a new governor, Dewitt Senter, the General Assembly called a statewide referendum on whether there would be a constitutional convention. The measure passed, and 69 delegates were elected from across the state.

The convention met in Nashville during the first few months of 1870. Here are some of the points I find especially interesting about the constitution they wrote:

- The Tennessee Constitution included a Declaration of Rights much longer than the U.S. Bill of Rights. It included the right to keep and bear arms, but it also declared that the General Assembly could “regulate the wearing of arms with a view to prevent crime” — something not stated in the U.S. Constitution.

- It banned slavery except as punishment for crime, using similar language to that in the 13th Amendment.

- It stated that no man over the age of 21 and who had not committed “infamous” crimes could be denied the opportunity to vote, provided he had paid his poll tax. It did not levy such a poll tax but said the General Assembly had the right to enact one (the legislature eventually did, but not until 1890). All money raised from such a poll tax would be earmarked for education.

- It gave the governor far less power than Johnson and Brownlow had wielded. Under the new constitution, the governor could not suspend habeas corpus or declare martial law without the approval of the General Assembly. The new constitution required only a majority vote in both houses of the legislature to override a veto — another way of limiting the power of the executive branch. Finally, the constitution set up three “constitutional officers” — the treasurer, secretary of state and comptroller — to be appointed by the General Assembly, not the governor.

- It made many changes to the way the judiciary was organized. It increased the size of the state supreme court from three to five members and made it clear that judges were to be elected from within their districts, not appointed by the governor. It also required judges to have lived in the state of Tennessee for at least five years — an item that targeted “carpetbagger” politicians.

- It required that Tennessee have “safe and comfortable” prisons — a reflection of the fact that so many soldiers and Confederate sympathizers had been jailed during the war (including former U.S. Sen. A.O.P. Nicholson, the convention’s most prominent delegate).

- It barred interracial schools and interracial marriage.

- It barred “ministers of the gospel” from serving as legislators (an item that may have been written with former Gov. Brownlow — a former Methodist minister — in mind).

The new constitution was approved by a vote of about 100,000 to 30,000 on March 21, 1870. It remained unchanged for 83 years but has been amended several times in the last three-quarters of a century — sometimes via constitutional convention and sometimes via referendum.

In 1953, for instance, a constitutional convention changed the term of the governor from two to four years and got rid of the clause that allowed for a poll tax.

In 1977, another constitutional convention got rid of the clauses banning interracial schools and interracial marriage as well as the item that limited loan interest at 10 percent (the so-called “usury clause”).

In 2002, voters decided by referendum to get rid of the constitution’s ban on lotteries.

In any case, I hope all this information helps teachers and students realize that the Tennessee Constitution is not set in stone. It is a living, changeable document with a story behind every item and clause.