On July 26, 1945, the USS Indianapolis delivered a crate to a tiny island in the South Pacific called Tinian. None of the crew knew why they had been ordered to rush across the ocean, none knew that the crate contained the key part of a new type of bomb and none knew that its contents had been created in a Tennessee city whose very existence was a secret.

The crew also didn’t know that the Indianapolis was on its last mission.

To understand the story of this doomed Navy ship, you have to go back three years. After President Franklin Roosevelt gave the go-ahead for the U.S. military to start working on an atomic bomb, the project was given the code name “Manhattan Project” and placed under the command of U.S. Army officer Leslie Groves who chose physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer to be scientific director of the project.

Groves, Oppenheimer and most of the key scientists worked at Los Alamos, New Mexico. Physicists weren’t sure about the best way to create the nuclear reaction in an atomic bomb. Some believed that the best way to do it was by making an element called plutonium; others believed they should use Uranium-235.

The decision was made to create both elements — plutonium in Hanford, Washington, and Uranium-235 at an East Tennessee site that eventually came to be known as Oak Ridge.

Why East Tennessee? For one thing, the Tennessee Valley Authority was providing huge amounts of electricity at the time. For another, Oak Ridge was surrounded by natural barriers such as ridges and rivers.

The Manhattan Project moved fast. In 1942 and 1943, the U.S. government acquired about 56,000 acres in Anderson and Roane counties from about 3,000 property owners. Families, some of whom had lived there for generations, were told that they had to leave their homes and farms in as little as three weeks because of a U.S. government project then referred to as the Clinton Engineering Works.

The government sent engineers and construction crews to build roads, power plants, houses, office buildings, schools, stores — everything necessary to have a military base and take care of all the needs of the thousands of people who would live and work there. The largest structures, by far, were manufacturing plants with names such as K-25, S-50, Y-12 and X-10. Most of the plants were involved in trying to separate Uranium-235 from Uranium-238, the most common type of uranium found in the ground.

Thousands of people were hired to work at Oak Ridge. They lived in homes assigned based on the types of jobs they had. Housing ranged from three-bedroom houses at the top end to one-room “hutments” that contained four beds and a pot-bellied stove in the middle.

Security was tight. The U.S. government did not want the outside world to know what was happening at Oak Ridge. A key security concept was “compartmentalization” — the idea that workers only knew what they needed to know to do their particular jobs. A worker at an Oak Ridge factory might monitor gauges, open or close valves or repair piping. But almost none of them knew why they were monitoring the gauges or opening and closing valves or what the purpose of the factory was in the first place.

“I went to my job every day and watched temperature gauges,” said Sue Wilkerson, who worked at one of the Oak Ridge plants and later became a resident of Obion County. “If the temperature rose, I turned a dial. If the temperature dropped, I turned another. We girls didn’t know what the other girls were doing because we weren’t allowed to talk about it.”

To make sure no one talked about what they did, the government had agents who would read mail, listen in on phone conversations and make sure people didn’t talk about what they were doing at work.

Under the original plan, the secret government city of Oak Ridge was to have about 12,000 residents. As the project grew and scientists realized it took more work and manpower to make Uranium-235 than they thought, the plans grew. By 1945, Oak Ridge had close to 75,000 people, making it the fifth-largest city in Tennessee. But since it was a secret city, Oak Ridge did not appear on any maps, nor did the very mention of its existence appear in any newspapers until after the war.

In the summer of 1945, small amounts of Uranium-235 were transported from Oak Ridge to New Mexico. President Harry Truman issued the Potsdam Declaration, warning Japan that it had to surrender unconditionally or face dire consequences. Japan did not surrender, and Truman made the decision to drop the first atomic bomb on Hiroshima.

On Aug. 6, 1945, a B-29 bomber called the Enola Gay took off from Tinian and dropped the atomic bomb on Hiroshima. It killed about 80,000 people instantly and about another 100,000 people in subsequent months.

Within hours of the bombing, the U.S. War Department revealed that key components of the new bomb had been created in Anderson County. A secret no more, there were stories about Oak Ridge in just about every newspaper in America.

And what became of the USS Indianapolis? Only four days after dropping off its mysterious crate, it was sunk by two Japanese torpedoes. About 300 of its 1,200-man crew died immediately, and another 600 of them perished during the next four days as they awaited rescue. Many of the crewmembers of the Indianapolis drowned. Others died from dehydration, and some died in some of the worst shark attacks in recorded history.

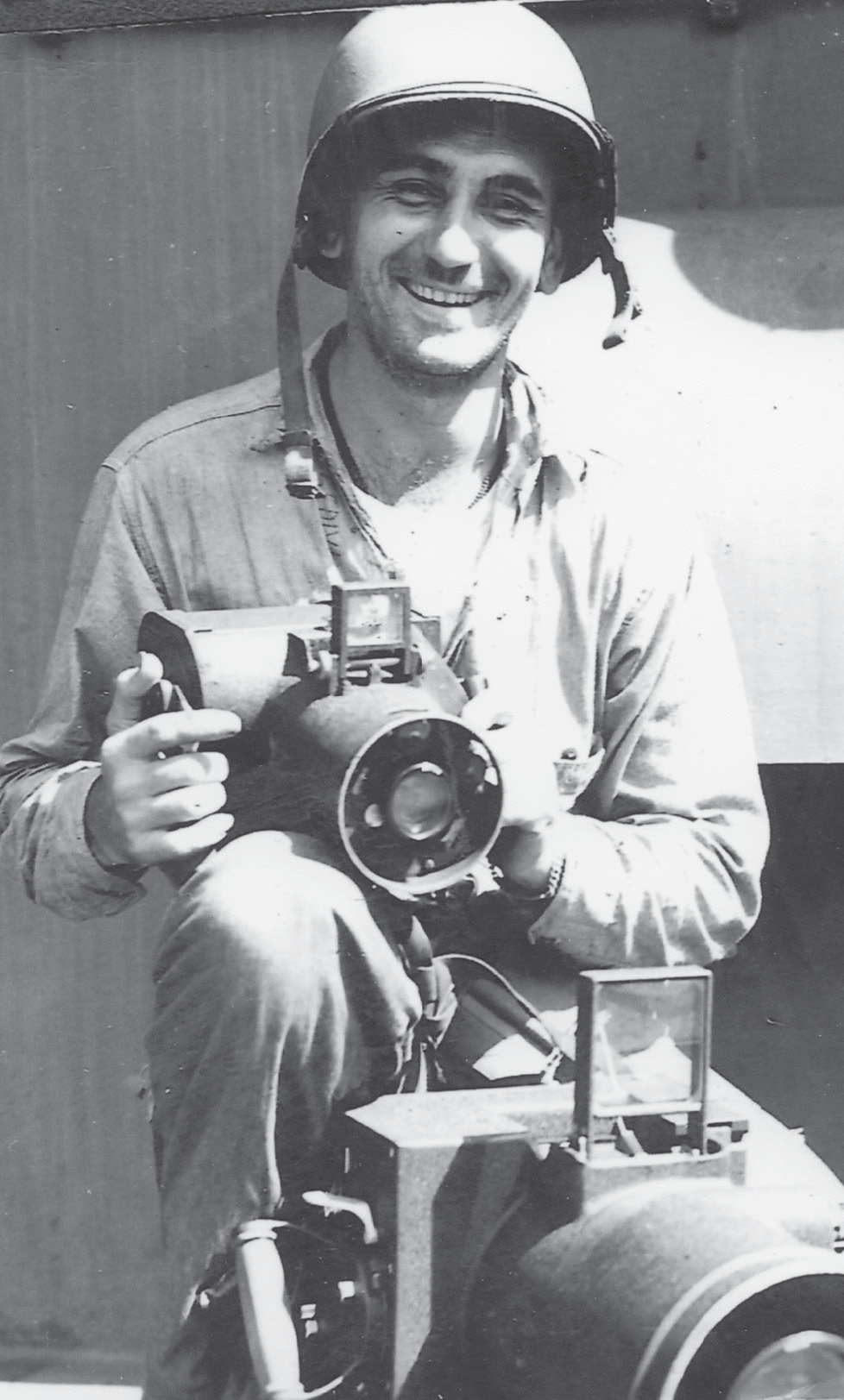

Most of the photos we have of the crew of the Indianapolis were taken by ship photographer Alfred Sedivi — one of the 900 crewmembers who perished.

Like the secret crate that the Indianapolis had delivered, Sedivi was from Tennessee — Nashville, to be exact. His family donated more than a thousand of the photographs he took while serving on board the Indianapolis to the U.S. Naval Institute Press. You can see them at photos.usni.org.

Thanks to Edward T. Sullivan, author of “The Ultimate Weapon: The Race to Develop the Atomic Bomb,” for his assistance in writing this column.

Alfred Sedivi, the photographer for the USS Indianapolis, was a resident of Nashville.