Fort Blount found after more than 200 years

The first week of May 1797 was an interesting time to be at Fort Blount. On the fourth of that month, John Sevier passed through. Sevier — hero of Kings Mountain and veteran of more than 30 armed encounters with Indians — was in his first year as governor of Tennessee.

Four days later, a Frenchman of apparent aristocratic birth, along with his retinue, arrived on horseback. Ridiculously out of place, the man identified himself as Prince Louis Phillipe of France. He said he and his companions had left Kingston three days earlier and were on their way to Nashville. In broken English, he said they were hungry and were willing to pay for any food.

The visitors from far away were disappointed by the accommodations. According to Louis Phillipe’s journal, “They gave us cornbread, a little milk and fatback of bear, salted and smoked, which we found impossible to swallow, hungry or no.”

One wonders whether it was the worst meal of his life. Years later, Louis Phillipe returned to his homeland and reigned as king of France from 1830 until 1848.

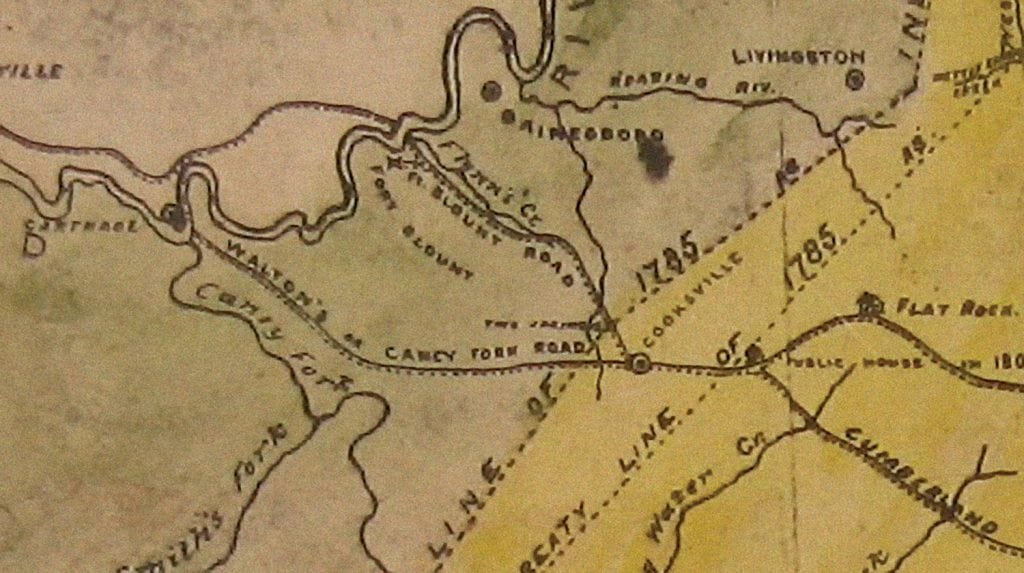

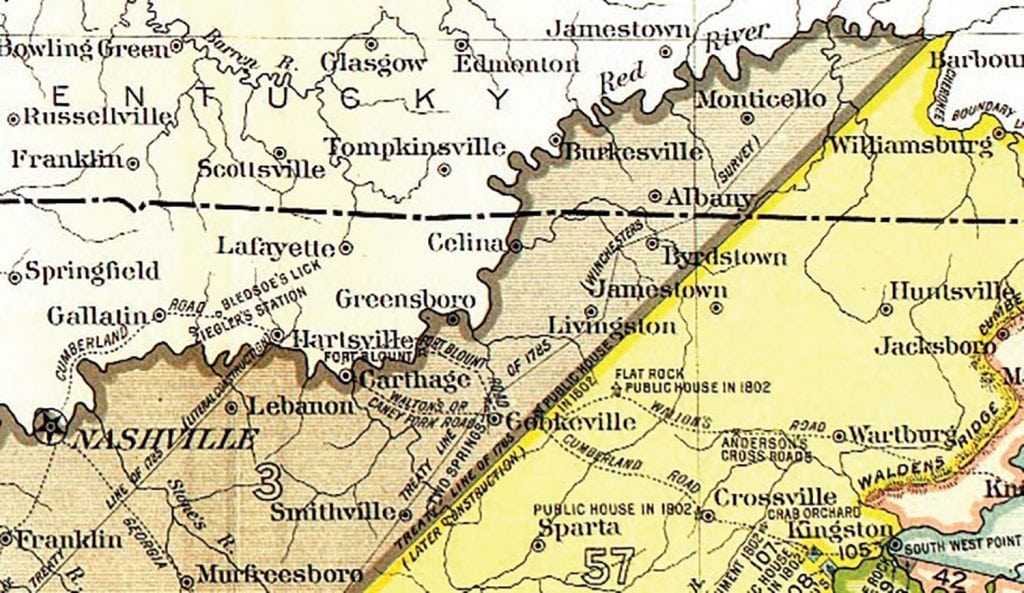

Fort Blount was a military outpost on the western edge of the Cumberland Plateau in present-day Jackson County. It was active in the 1790s when settlers claimed much of what is now Middle Tennessee, but the Cherokee nation was still recognized as the owner of the Cumberland Plateau. At a time when Indian attacks were still frequent, families migrating west would stop at Fort Southwest Point (in present-day Kingston). They would then ride or walk across the mountains with armed guards as far as Fort Blount, where they would cross the Cumberland River by ferry. From there they took a route (now referred to as Avery’s Trace) through present-day Trousdale and Sumner counties and into Nashville.

Originally known as the “Crossing of the Cumberland,” we think a blockhouse was built there in 1792. By 1794, it was known as Fort Blount and included a palisade wall.

The list of people who passed through the area doesn’t just include the king of France and the first governor of Tennessee. In 1788, when the road was first opened but the fort was not yet built, at least 60 families crossed the Cumberland River there on their way to Nashville. Andrew Jackson passed through on his way west that same year.

A few months ago, I wrote a column that mentioned the Nickajack Expedition, the decisive attack on the Chickamaugans west of present-day Chattanooga in 1794. The chief scout for the Nickajack Expedition was Joseph Brown, a young man whose family had been attacked by the Chickamaugans and who had spent a year living with them before he and his sisters were released. No sooner had Brown made his way back to Nashville than he volunteered for duty at Fort Blount. He was there for about a year, starting in April 1795.

In March 1796, French botanist Andre Michaux spent the night at Fort Blount and discovered in the woods near the fort a species of tree previously unknown to Europeans. Today we know this tree as the yellowwood, and in 1991, it was designated as Tennessee’s Bicentennial Tree.

Like many frontier installations, Fort Blount was not active for long. Indian attacks died down by 1796. The state of Tennessee and the federal government withdrew troops from the area about two years later. Not long after that, William Walton started a new ferry service about 20 miles southwest in a community later known as Carthage. People stopped passing through the Fort Blount area as they crossed Tennessee.

There remained a small community near the site of Fort Blount called Williamsburg, named for Sampson Williams, owner of the land on which the fort sat. For a time, Williamsburg was the seat of Jackson County. Eventually, however, the community died away, and the fort was torn down — or fell down.

As the decades passed, people forgot where the fort had been. They knew the fort was close to Sampson Williams’ gravesite, but some early accounts said it was one side of the river; some said it was on the other.

In the 1980s, state of Tennessee archaeologist Sam Smith became fascinated with Fort Blount because of extensive research he conducted at Fort Southwest Point. The Division of Archaeology secured grants to learn what it could about Jackson County’s forgotten frontier garrison.

Using old maps, journals and a lawsuit involving Sampson Williams, archaeologists were able to come up with a pretty good guess as to where to start digging. “The general area had been long suspected,” says Benjamin Nance, who took part in the project and still works for the Division of Archaeology. “But it took extensive research to narrow down enough of an area to test archaeologically.”

Archaeologists quickly discovered that Fort Blount was on the west side of the river. They found evidence of several structures, including an arrangement of post holes that appear to have been dug to build a palisade wall.

They also found thousands of pieces of kitchen artifacts, hundreds of pieces of kitchenware, 38 musket balls and 181 buttons. They found a stock clasp, a military button with an eagle on it and a button that indicated the owner had been a member of the Fourth Infantry Regiment — which had been stationed at Fort Blount.

They even found nine coins — eight of which were made in Spain and one that was marked with the year 1781.

“It was a pretty cool project,” Nance says.

The dig put to rest the long debate about exactly where Fort Blount was. However, 20 years later, the former site of the fort remains a combination of private and Army Corps of Engineers property. There are no plans for the state to acquire the land or for anyone to build a historic park or replica of the fort.

So Fort Blount, the place through which a famous botanist, governor, president and king all passed, is and will remain a little-known chapter of Tennessee history.