… but wins an election and builds his myth

In 1825, David Crockett lived in a cabin in West Tennessee in what is now Gibson County. His favorite thing to do was to hunt, sometimes for a few hours and sometimes for a few days. They didn’t have cell phones back then. His wife didn’t like it when he wandered off and wasn’t heard from for a week. But such was the life of Betsy Crockett.

A lot more things were made of wood back then than there are today. Buckets were made of wood. Whiskey was shipped in big wooden barrels. Even the wheels on horse carriages were made of wood.

All you had to do was get the wood to a town, where the factories were located. That was the hard part.

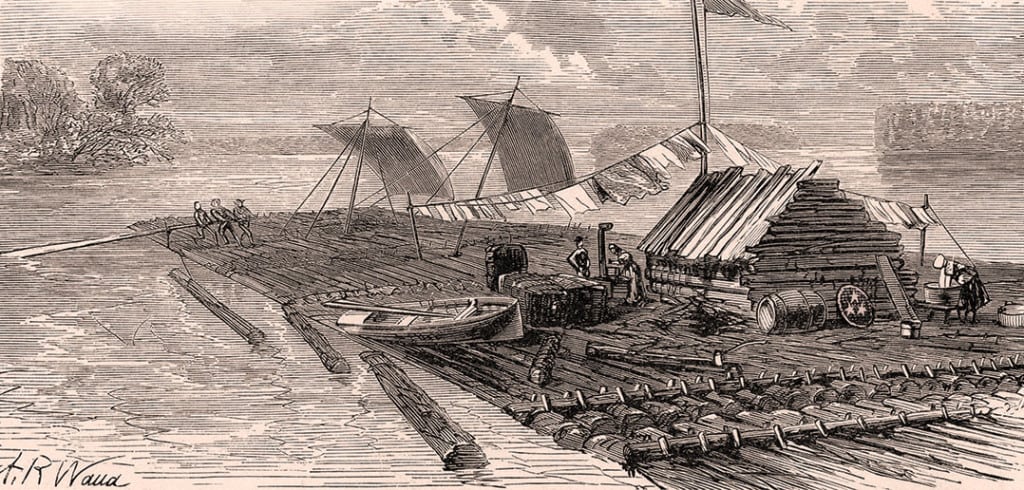

Crockett came up with a plan to make money. He and some other men would chop down trees and cut them up into pieces called staves. They would stack the staves all nice and neat and put them on two huge log rafts. They would then get on the rafts and steer them down the Obion River to where it meets the Mississippi River. From there they would float downstream to New Orleans and sell the staves.

What a great plan! What could go wrong?

Crockett hired some men to help him chop down trees and cut them into staves and make the log rafts. He couldn’t afford to pay them then, so he promised to pay them later, after he’d sold the staves. He also promised to feed them all the bear meat they could eat while they worked.

While all the men were chopping down trees, Crockett was hunting with his dogs. This was his favorite thing to do, and he was a great hunter. But he had to be careful. You see, there had been a lot of big earthquakes a few years earlier. That’s why people called that part of Tennessee “the land of the shakes.” Because of these earthquakes, there were big open cracks in the earth. Crockett was constantly pulling his dogs out of the cracks, and he had to be careful that he didn’t fall into one and never be heard from again.

In any case, Crockett brought in a lot of bear meat. And within a few months his hired hands had chopped 30,000 staves!

It was around March of 1826 when Crockett’s two rafts, loaded down with wooden staves, shoved off and headed down the Obion. The river was high, and the current moved quickly. The only thing Crockett and his men had to do was use big sticks and the rudders to keep the rafts in the middle of the river. Things went pretty well at first.

When they hit the big river, now that was a different story. From the moment the two flatboats floated out onto the “mighty Mississip,” they felt like they were on a fast-moving ocean. They had no idea how to control their rafts, steer their rafts or even stop their rafts. Crockett had his men tie the rafts together. But that didn’t help any.

One night Crockett and his men tried to steer to the shore. They could not. They floated all night in the dark, huge river, with no idea what was in front of them. At some point, they passed a town. They didn’t know what town it was, but they knew it was a town. People waved lanterns, trying to yell instructions on how to stop. “The people would run out with lights, and try to get us to shore, but all in vain,” Crockett wrote in his autobiography.

But there was no use. They kept on a-going.

Somehow they made it through a turn in the river known as the Devil’s Elbow. For a while, Crockett began to think they could make it all the way to New Orleans. But then their luck ran out. The rafts crashed into a large tree that was stuck in the river. Both boats tipped over, and all the men were thrown overboard. Crockett was lucky he didn’t drown.

Everyone clung to a pile of driftwood. All the staves were gone, and the men were cold. But they were glad to be alive.

“I felt happier and better off than I had in my life before,” Crockett wrote, “for I had made such a marvelous escape, that I had forgotten almost else in that; and so I felt prime.”

As luck would have it, a boat came by and picked them up. A few hours later, the boat landed in Memphis. It was greeted by a large crowd that included Marcus Winchester. He knew who Crockett was and was excited to see him.

Winchester owned a big store in Memphis, not far from the river. This turned out to be a good thing because Crockett was not wearing any pants when the boat fished him out of the Mississippi. Somehow they had fallen off as he struggled to stay alive in the river.

Winchester sent someone to get Crockett a pair of pants. He invited Crockett and his men into his house, which was one of the biggest in Memphis. He fed them and gave them a place to stay. And he loaned Crockett some money.

Crockett sent some of his men home. Then he got on a boat heading downstream in search of what was left of his flatboats. He went all the way to Natchez, Miss. But he never found his flatboats or his staves.

It was a long horse ride home up the Natchez Trace. When he got back to Tennessee, he explained the story to all the men he had hired. Since he couldn’t pay them, they didn’t think the story was funny. Crockett also had to explain it to his wife, Betsy, who by this time was used to his tall tales. She wasn’t amused either, even when he told her the part about losing his pants.

Other people loved the story, though. They lived in other parts of West Tennessee, in counties such as Carroll, Henderson and Madison. When Crockett ran for Congress the next year, he told stories about bear-hunting and floating uncontrollably down the Mississippi and being fished out of the river with no pants on. People laughed. They elected him to Congress.

And it was there, in Washington, D.C., that David Crockett first became a national hero.

This story is included in the Tennessee History for Kids booklet “Journey of the Adventure and other stories.” The original version of this story can be found in the autobiography “A Narrative in the Life of David Crockett of the State of Tennessee,” originally published in 1834.

Go to tnhistoryforkids.org to learn more tales of Tennessee history.