It’s hard to imagine Nashville without the Capitol, state office buildings and thousands of state employees — let alone the annual spectacle known as the Tennessee General Assembly. But it almost turned out differently. In fact, thanks to Nashville’s reputation as a den of political iniquity, the Capitol nearly ended up in some other place.

For the first few decades of Tennessee’s existence, the legislature couldn’t agree on a permanent capital. Knoxville was the first seat of government in 1796, followed by Nashville in 1812, Knoxville again four years later, Murfreesboro in 1819 and Nashville again seven years later. Along the way — in one of the strange footnotes of Tennessee history — Kingston served as state capital for one day in 1807.

Tennessee might have had a temporary capital for a lot longer had it not been for William Carroll, who served 12 years as governor in the 1820s and 1830s. Carroll led the fight to create a chancery court, the state’s first penitentiary and the state’s first insane asylum (as homes for the mentally handicapped and mentally ill were then called).

Carroll was also responsible for organizing Tennessee’s Constitutional Convention of 1834 — a convention that debated the idea of a permanent capital at some length. Like many legislative bodies, however, it could come to no consensus and therefore decided to force other people to make the tough decision some other time: The delegates recommended (and the voters later approved) a constitutional amendment requiring the legislature to pick a permanent seat of government by 1843.

When the legislature met at the Davidson County Courthouse in October 1843, it spent the first week arguing over where to put the Capitol. House and Senate members took turns espousing the virtues of their hometowns, proposing the seat of government be placed there. Then the vote would be taken, the measure would fail and another representative or senator would stand up and espouse the virtues of his hometown.It went on and on. Over the course of the week, just about every organized community in Tennessee got its chance and lost. During the Senate debate on the morning of Oct. 4, Kingston, Lebanon, Hamilton, Sparta, Knoxville, Clarksville, McMinnville, Shelbyville, Murfreesboro, Chattanooga, Franklin, Harrison and Woodbury were all considered and voted down. After lunch, the Senate considered and rejected Sparta (again), Franklin, Harrison (again) and Woodbury. Then, late on the afternoon on Wednesday, Oct. 4, the State Senate passed a bill 13-12 to make Kingston the permanent capital of Tennessee.

Over in the 75-member State House, members were also taking a tour through Tennessee. The House considered and rejected the idea of putting the Capitol in Nashville, Carrollville (the riverside town in Wayne County now known as Clifton), Sparta, Carthage, Nashville (again), Smithville and Murfreesboro. After lunch, towns suggested but voted down included Knoxville, Jackson, Carthage (again), Knoxville (again), Savannah, Jackson (again), Manchester, Murfreesboro, Lebanon, Sparta (again) and Paris. Finally, in the early evening — about the same time the Senate passed a bill to make Kingston the permanent capital — the House passed a bill making Murfreesboro the permanent capital.

That night would have been an exciting news night for Kingston and Murfreesboro. But Tennessee didn’t have the telegraph yet, so there was no way that people in those communities could have known that they were so close to potential glory.

On Friday, Oct. 6, the House started up again. “The name of almost every town from Sullivan to Shelby successfully proposed,” the Knoxville Post reported. House members suggested and rejected Columbia, Harrison, Charlotte, Reynoldsburg, Shelbyville, Smithville, Manchester, Woodbury, Monticello (in Putnam County) and Chattanooga. This time, Chattanooga prevailed.

A few minutes later, the Johnson County community of Taylorsville prevailed. Then Columbia prevailed. The House then spent the rest of the afternoon debating a measure to locate the state capital “at the most eligible point within ten miles of the geographic center of the state.” Among the people who spoke in favor of this proposal was Rep. William Hawkins Polk of Maury County — “a younger brother of the ex-governor, and thought by some in his party to be a more talented man” (this was before James K. Polk became president).

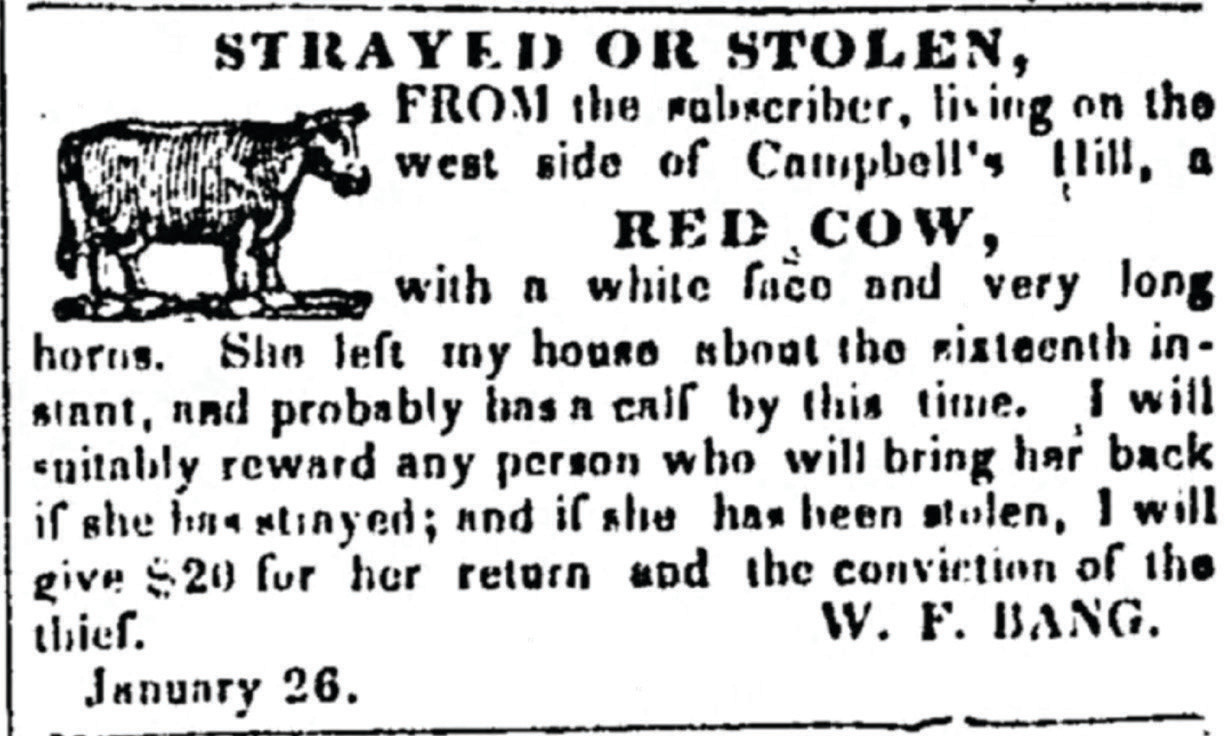

It eventually came down to Nashville and Murfreesboro, and it was then, on Saturday, Oct. 7, that the debate got ugly. Several legislators said Nashville was the logical choice. After all, the legislature was used to meeting there, it had better road and water connections and it contained institutions (such as the bank and prison) that the legislature needed to keep an eye on. The city of Nashville was also offering the state a hill on which to build a Capitol building. Acquired by attorney William Campbell years earlier as a fee for a lawsuit, several Nashville citizens had signed an option to buy Campbell’s Hill for $30,000 to donate it to the state.

Lawmakers advocating for Murfreesboro did not go down easily. State Sen. Samuel Laughlin of Warren County argued passionately against Nashville, pointing out that the geographic center of the state was in Rutherford County. (In fact, at the behest of legislators from Rutherford County, the state had hired a mathematician to calculate the geographic center of the state. In 1976, the Rutherford County Historical Society paid for an obelisk to be built there. You can find it today just north of Middle Tennessee State University.)

Laughlin also noted that since the legislature moved to Nashville 17 years earlier, the General Assembly was meeting for longer, and the government had increased its annual expenditure and taken on tremendous debt. This, he said, could be attributed to the forces at work in Nashville, which he described as “this political Sodom.”

State Sen. William Henry Sneed, representing Rutherford and Williamson counties, agreed with his colleague and added points of his own. “The people of Nashville are the creditor class,” he said, according to the Nashville Union. “They were traders, speculators … while the largest portion of the people elsewhere are farmers. The interests of the two classes are averse, and their opinions, of course, at variance.”

Sneed made reference to Nashville’s “voluptuousness” and “dissipation.” He also implied that the citizens of Nashville were bribing the legislature by offering it free land — a curious point, considering Murfreesboro was also offering the legislature free land.

That evening, the House voted 50-23 to make Nashville the state’s permanent capital. The next day, the Senate concurred by vote of 17-8.

Two days later, the Republican Banner had this to say: “The question being thus settled, let all the unpleasant circumstances connected with the conflict for the location of the Seat of Government be laid aside forever; let all thoughts of that controversy be buried in the grave of oblivion.”

And what became of State Sen. Sneed of Rutherford County? Two years after the capital debate, he moved to Knoxville and set up a law practice there. One of his clients was the newly formed Hancock County — a county whose creation in 1844 had been legally challenged. Sneed represented Hancock County in that lawsuit, which went all the way to the Tennessee Supreme Court and which Hancock County won in 1848. In gratitude, the county seat, previously known as Greasy Rock, was renamed Sneedville.

Sneed was elected to Congress in 1855, on the eve of the Civil War, and was a leader in Knoxville’s secessionist movement. This put him at odds with William Gannaway “Parson” Brownlow, a unionist and newspaper editor who was, in my opinion, the greatest insulter in Tennessee history. Brownlow hated Sneed so much that he advocated his execution in print. “They (Confederate leaders in Knoxville) have filled East Tennessee with widows and orphans; they have destroyed houses and barns, fences and homes; they have plundered honest men of their stock and grain, and they have filled the land with mourning,” Brownlow said of Sneed and his compatriots. “Let such imps of Hell die the deaths of traitors.”

Sneed died in 1869. I don’t think many people in Rutherford County, Williamson County, Hancock County or Knox County remember him today.