I have to admit that I find many biographies hard to wade through — especially those written in scholarly style and with footnotes on every page. On the other hand, I find autobiographies fascinating. An autobiography tells you the words a person used, the way he or she saw the world and (if you read between the lines) all about the times in which the person lived.

Here are some of my favorites:

“A Narrative of the Life of David Crockett of the State of Tennessee” (1834)

It is hard to know how accurate Crockett’s autobiography is since the man had a tendency to stretch the truth, and we don’t know how much of it was embellished by his ghost writer. But I do think the phrases and jokes in the book are authentic. They have made me laugh out loud more than once.

For instance, Crockett mentions a woman he met who was “well enough to smartness, but she was as ugly as a stone fence.” He admits that as the years passed, he was “better at increasing my family than my fortune.” And speeches in Congress, Crockett claims, are so boring that “it’s harder than splitting gum logs in August to stay awake.”

“Company Aytch: Or A Sideshow of the Big Show” (1900)

Sam Watkins’ book about life as a soldier in the Confederate Army is one of the most touching personal accounts of any private in any war. In one unforgettable passage, he describes being forced to watch the execution of two U.S. Army soldiers accused of spying on the Confederacy:

“The two little boys were rushed upon the platform. I saw that they were handcuffed. ‘Are they spies?’ I was appalled; I was horrified; nay, more, I was sick at heart. One was about fourteen and the other about sixteen years old, I should judge. The ropes were promptly adjusted around their necks by the Provost Marshal. The youngest one began to beg and cry and plead most piteously. It was horrid. The older one kicked him, and told him to stand up and show the Rebels how a Union man could die for his country. Be a man! The charges and specifications were then read. The props were knocked out and the two boys were dangling in the air. I turned off, sick at heart.”

“Crusade for Justice: The Autobiography of Ida B. Wells” (1970)

Ida Wells fought racial injustice in the South more than 130 years ago, but her autobiography reads like it was written last month. One of the most compelling stories predates her role in the early civil rights movement. In this scene, she describes what happened after her parents died, when several men stood in her family’s house and decided that all of her younger brothers and sisters would be scattered to other households to be cared for. Wells later recalled:

“When all this had been arranged to their satisfaction, I, who said nothing before and had not even been consulted, calmly announced that they were not going to put any of the children anywhere; I said that it would make my father and mother turn over in their graves to know their children had been scattered like that and that we owned the house and if the Masons would help me find work, I would take care of them.”

The 14-year-old Ida Wells found a job as a teacher and managed to keep her brothers and sisters together.

“Father of the Blues: An Autobiography” by W.C. Handy (1941)

I read this book last year and was amused by the fact that W.C. Handy’s father went to great lengths to stop his son from having a career in music — including making young W.C. return a guitar he bought with money he saved up. “Take it away, I tell you!” Charles Handy told his son. “Get it out of your hands. Whatever possessed you to bring a sinful thing like that into our Christian home?”

Since W.C. Handy turned out to be one the great composer/musicians of his era, this anecdote did make me wonder whether we modern-day parents have it all wrong. If we want our kids to grow up to be great musicians, should we maybe refuse to let them bring a musical instrument into the house? It worked for Charles Handy.Civil rights leader Myles Horton says in his autobiography, “I took the gamble of doing something about a moral problem instead of simply talking about it.”

“Doctor Woman of the Cumberlands: The Autobiography of May Cravath Wharton” (1953)

One of the overlooked heroes of Tennessee history, Wharton moved to the Cumberland County community of Pleasant Hill during World War I. For many years, she was the only physician for miles around. In her autobiography, she describes what it was like to travel through her part of the state (often on foot or by mule) and treat people in their tiny log cabin homes who were suffering from life-threatening diseases. It is a touching story that makes it very clear why some folks in Cumberland County still revere the name May Wharton.

“I resolved that mothers should be saved; that little children should be given a fair start in life; that pneumonia, pellagra, diabetes, anemia and all the rest should not go on and on until no medical skill should cure them; that the old and invalid should have some comfort and care even when they could not be mended; and that those far from doctors should have medical aid brought within reach — of their homes and their thin pocketbooks,” Wharton wrote.

“First Lady of the Seeing Eye” by Morris Frank (1957)

Nashville native Morris Frank was the first blind man to train and use a Seeing Eye dog, and the title of the book refers to his German shepherd. However, this is, in every sense of the word, Frank’s autobiography — the fascinating story about how his dog, Buddy, helped transform his life from a lonely one into one in which people were constantly talking to him.

In his book, Frank describes the way New Yorkers reacted when they realized his dog was leading him around the city. “Everywhere people were attracted to Buddy,” he wrote. “They spoke to her, petted her, offered her sweets. But she refused to be distracted, did not get irritated or side tracked, and did her work magnificently and with obvious pleasure. In a week Buddy had conquered the biggest city in the world. She was a celebrity in a town that loves nothing better.”

“The Long Haul: An Autobiography” by Myles Horton (1990)

Horton has many stories about Martin Luther King Jr., Rosa Parks and other civil rights leaders who were influenced by the Highlander Folk School, which he founded.

I was intrigued by many stories in this book — such as the time, in 1928, that he organized an integrated (and thus illegal) dinner that included white and black high school students at the YMCA in Knoxville. After some hemming and hawing, the waiters shrugged and served everyone at the meal — quite possibly the first publicly integrated event in the city’s history. “I took the gamble of doing something about a moral problem instead of simply talking about it,” Horton wrote. “I just reversed the process that was going on in the universities and churches, and over 120 people learned that they could change things if they wanted to.”

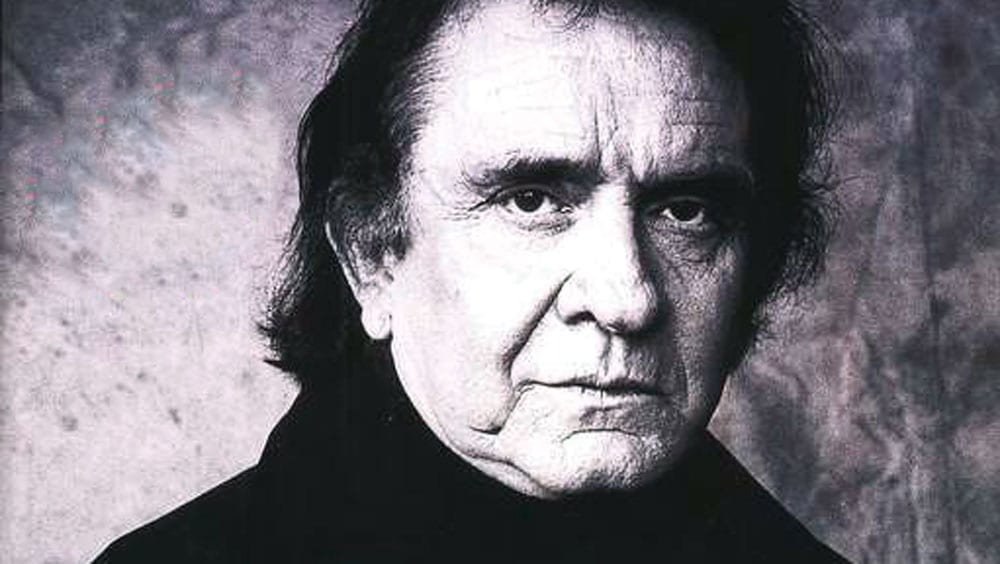

“Cash: The Autobiography” (1997)

Johnny Cash was a Tennessee history buff. He was especially interested in the Chickamaugan Indians and the geography of the Tennessee River just downstream from Chattanooga, and he wrote about both in a song called “The Whirl and the Suck.”

Cash also went through a stage of his life when he was addicted to drugs. In his autobiography, he says that, in 1967, he chose Nickajack Cave to be the site of his suicide because of all the events that had occurred there. “(An) army had slaughtered the Nickajack Indians there, men, women and children, and soldiers from both sides of the War Between the States had taken shelter in the caves at various times during the conflict.… If I crawled in far enough, I thought, I’d never be able to find my way back out, and nobody would be able to locate me until I was dead, and indeed if they ever could. (Nickajack Dam) was going in soon.”

Instead, Cash found Jesus, crawled out of the cave and turned his life around. “I told my mother that God had saved me from killing myself. I told her I was ready to commit myself to Him, and do whatever it took to get off drugs. I wasn’t lying.”