Charles Coolidge of Signal Mountain recently received quite a bit of publicity, and deservedly so. Tennessee’s last living World War II Medal of Honor recipient was honored at a three-day event that launched the new Medal of Honor Character Development Program in Middle Tennessee.

This seemed like a good opportunity to point out that eight Tennesseans received the Congressional Medal of Honor during World War II. These awards are given to people who go “above and beyond the call of duty” and risk their lives while engaged in an action against an enemy of the United States.

Elbert Kinser was a farmboy from Greene County who enlisted in the U.S. Marine Corps. On May 4, 1945, during the Battle of Okinawa, he threw himself on a live grenade, sacrificing his life to save several fellow Marines.

Camp Kinser, a Marine base at Okinawa, is named for him.

Knoxville native Troy McGill was killed in March 1944 at the battle over a Pacific Island called Los Negros. As military citations go, his may be the most succinct:

“With the enemy only 5 yards away, he charged from his foxhole in the face of certain death and clubbed the enemy with his rifle in hand-to-hand combat until he was killed,” his medal citation says. “At dawn, 105 enemy dead were found around his position.”

Today, a portion of Interstate 40 in Knox County is named for McGill.

Maury County native John Harlan Willis was a corpsman in the Navy. Willis spent the war with a Marine unit that took part in the Battle of Iwo Jima, among other conflicts.

During the battle, Willis was administering blood to a patient when a grenade landed in the foxhole in which he was standing. He threw it out. Another landed beside him, and he threw it out. This happened again and again until the ninth exploded in his hand, killing him.

The Navy named a ship after this war hero from Tennessee. The USS John Willis (DE-1027) was part of the American fleet from 1957 until 1972.

Kinser, McGill and Willis received their medals posthumously, which means their families received their medals after the heroes died. Here are the Tennesseans who came home and received their medals but have died since then:

Like Kinser, Raymond Cooley of South Pittsburg threw himself on a live grenade (in the Philippines) to save the lives of several of his fellow soldiers. Unlike Kinser, Cooley lived to come home.

However, Cooley’s postwar life was short and tragic. With one arm amputated and still heavily affected by his war wounds, Cooley died in a one-car accident in 1947. Today, a part of Highway 28 in his home Marion County is named for him.

When the Allied armies invaded Italy in January 1944, one of the fiercest battles took place at a beachhead called Anzio. Paul Huff, a Bradley County native, was fighting there when he crawled alone in the face of heavy machine-gun fire (for an estimated 75 yards) to determine the strength and location of a German company entrenched atop a hill. Later, Huff led a group of 12 men who fought and won a six-hour battle over that hill.

Huff died of natural causes in 1994. Today, a major thoroughfare in Cleveland is named for him.

Charles McGaha of Cocke County was fighting in the Philippines in February 1945 and crossed a road under a hail of bullets to save an injured comrade. Injured, he returned to his men, then removed another wounded soldier. Then he carried a third man to safety, finally collapsing from loss of blood and exhaustion.

McGaha was stabbed to death in 1984 at the office of his taxi cab company in Columbus, Ga., where today a small section of road is named for him.

Hardin County native Vernon McGarity received his medal for deeds performed during the Battle of the Bulge. McGarity was injured, returned to battle and then braved enemy gunfire to rescue two wounded soldiers and destroy German weapons.

McGarity spent the last several months of the war in a German prisoner-of-war camp. He died in 2013 at the age of 91.

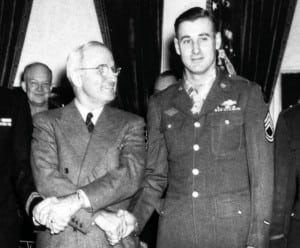

This brings us to 94-year-old Charles Coolidge, the last living Tennessee Medal of Honor recipient from World War II. Coolidge was a sergeant in the Army fighting in France in October 1944. He took command of a group of relatively inexperienced soldiers who ran into a company of German infantry and tanks. Coolidge and his men repelled the attacks.

“Coolidge armed himself with a bazooka and advanced to within 25 yards of the tanks,” according to the official citation. “His bazooka failed to function and he threw it aside. Securing all the hand grenades he could carry, he crawled forward and inflicted heavy casualties on the advancing enemy.” He then led his men in doing the same.

Chattanooga’s downtown riverfront park is named for Coolidge.