Former slaves who left the South to move north and west in the 1870s were known as Exodusters. Many of them migrated under the leadership of a former slave from Nashville.

Benjamin “Pap” Singleton was born in 1809 and escaped to the North when he was 37. “I have been a slave,” he later said to a U.S. congressional committee. “Fled to Canada when my children were small, and 19 years after, when I returned, they were grown.”

After the Union Army took over Middle Tennessee during the Civil War, Singleton moved back to Nashville and went to work as a cabinetmaker. As the war ended, he had high hopes for the future of African-Americans in the South. But after the Ku Klux Klan became a major force and after voting power was effectively taken away from former slaves, he became convinced that black people would never receive fair treatment in the South.

In 1874, Singleton and a Sumner County minister named Columbus Johnson co-founded a firm called the Edgefield Real Estate and Homestead Association. It went into the business of moving African Americans from Middle Tennessee to places in Kansas.

“Brethren, Friends & Fellow Citizens,” one of the company’s handbills said. “I feel thankful to inform you that the Real Estate and Homestead Association will leave here the 15th of April 1878 in pursuit of homes in the southwestern lands of America, at transportation rates cheaper than ever was known before.”

Why Kansas? For one thing, the Homestead Act of 1862 said that any U.S. citizen could lay claim to 160 acres of land there if they lived on the land for five years, improved it and built a home on it. There was also something symbolic about Kansas, the state that produced abolitionists such as John Brown.

In the late 1870s, about 120 African-Americans left Nashville at a time by steamboat, bound for St. Louis. From there they took the train to communities along the railroad such as Dunlap, Kan. Others settled in more established communities such as Topeka, where an entire part of the city became known as “Tennessee Town.”

Under Singleton’s leadership, as many as 8,000 people left Tennessee for Kansas in this manner.

How did these migrants make out? Some of them didn’t remain in rural Kansas for long, run off by the lack of water, blizzards, prairie fires and other difficulties of life in that part of the world. But some of them stayed, and their descendants still live in Kansas.

The Exoduster movement also created a surge in the African-American population of St. Louis. You see, many of the migrants got to St. Louis but couldn’t afford to go farther. Thousands of them were stranded, and they eventually put down roots.

By 1881, publicity surrounding Singleton and the migration had resulted in more African-Americans leaving the South for states such as Nebraska, Missouri and Indiana. Singleton was brought to Congress to testify about the movement, which had its share of critics, especially among white elected officials from the South. By this time, the Exoduster movement had largely ended.

For more details on Singleton and the Exoduster movement, read “The African-American History of Nashville, Tennessee, 1780-1930.”

There’s more on the Web

Go to tnhistoryforkids.org to learn more tales of Tennessee history.

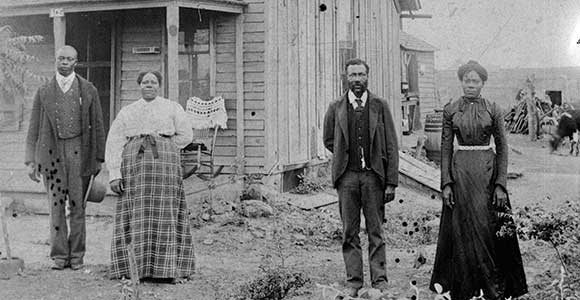

CAPTION: These four people moved from Tennessee to Kansas as part of the Exodusters movement. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, HABS KANS,33-NICO,1–6