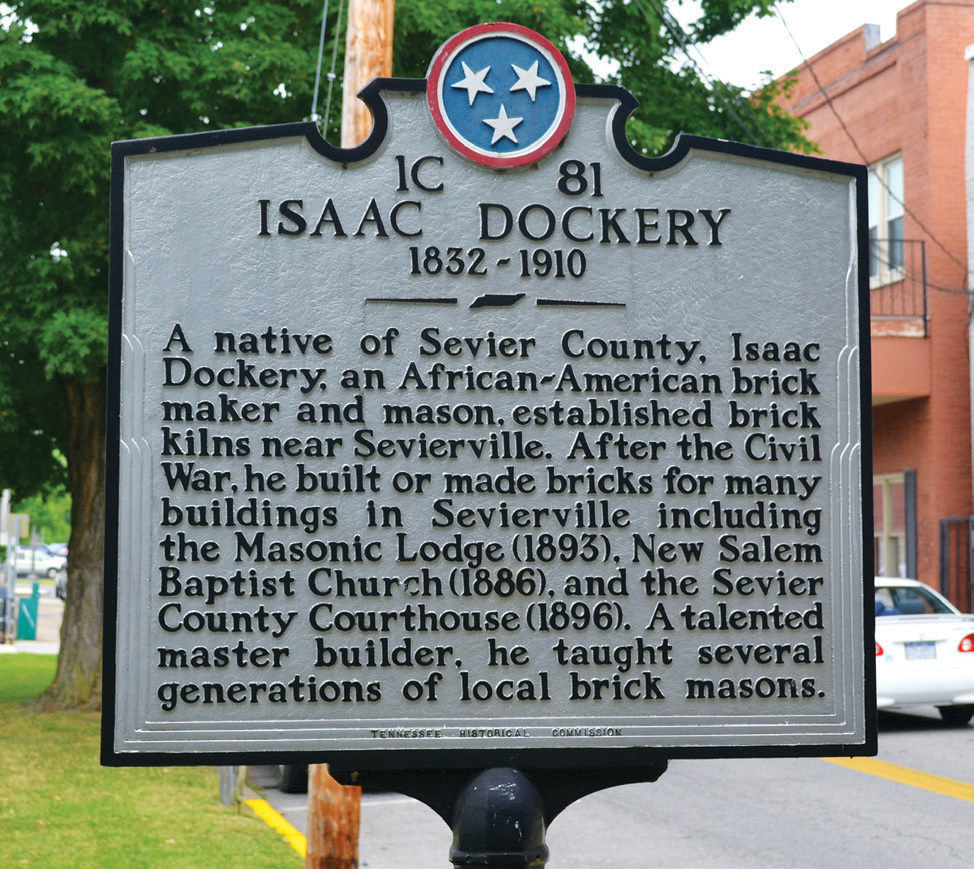

There were 4,510 free African Americans in Tennessee in 1830 — a number that grew to 7,300 by 1860. In recent years, we’ve learned more about these “free persons of color” — as they were known at the time. There are even historical markers to celebrate them such as the one at the Sevier County Courthouse that honors brickmason Isaac Dockery.

However, we need to put in context the word “free” when we refer to African Americans who lived in Tennessee before the Civil War. Black Tennesseans who were not enslaved had to abide by many laws that would have affected their lifestyles, relationships, career choices and quality of life. For instance:

“Free persons of color” could not vote in Tennessee, under the 1834 Constitution.

“Free persons of color” were required to register with the clerk of the county in which they lived. He or she was required to register their name, age and color, along with “any apparent mark or scar on his or her face, head or hands.” The county clerk would make two copies of the certificate verifying that the person was free — one to remain at the courthouse, the other for the Black person to carry as proof that they were not enslaved. Without the certificate, “free persons of color” were in danger of being mistaken for runaways.

“Free persons of color” were not allowed to have in their homes any enslaved person at night or Sunday “without permission of the owner or employer of such slave.” If, for instance, a free Black person had a child or parent who was enslaved, they pretty much couldn’t have this family member as a guest at their house.

“Free persons of color” were not allowed to marry enslaved people without permission of their slaveholder. A free Black man who married an enslaved Black woman and who took her away from her slaveholder was guilty of “negro stealing” — a crime punishable by two years in the state penitentiary.

“Free persons of color” weren’t allowed to marry people who were not also “of color,” since Tennessee law forbade a “white person to marry a negro, mulatto, or other person of mixed negro blood.”

“Free persons of color” weren’t allowed to give or sell alcoholic beverages. So, free Black people couldn’t own or work in an inn or store that served beer or whiskey, at least in a role that involved selling or serving the beer or whiskey.

“Free persons of color” were not allowed to “buy from or sell to a slave any goods or commodities or other things without written permission from the master, setting forth the articles to be bought or sold.” So, if an enslaved person was a craftsman and made things out his or her hands, it was illegal for a free Black person to purchase from that enslaved person something he or she had made.

“Free persons of color” were not allowed to write anything that could possibly be interpreted as encouraging enslaved people to rebel. “No person shall, in this State,” Tennessee law said, “may write, print, paint, draw, engrave or aid or abet in writing, printing, painting, drawing or engraving on paper, parchment, linen, metal or other substance with a view to its circulation, any paper, essay, verses, pamphlet, book, painting, drawing or engraving, calculated to excite discontent, insurrection or rebellion amongst the slaves or free persons of color.”

“Free persons of color” from other states were not allowed to move to Tennessee, with the maximum visit time being 20 days.

“Free persons of color” could be jailed for “refusing to work” — a clause that referred to the act of going on strike.

“Free persons of color” were forbidden from owning businesses that engaged in the act of “peddling and bartering.” As best I can tell, this law (which went into effect in April 1856) would have prohibited free Black people from owning businesses that sold products of any kind and traveled from place to place.

As for education, laws varied by date and location. There were, obviously, some free Black people (and some enslaved Black people) who could read and write. However, the legality of schools for African Americans varied by date and location. In 1850, the Nashville Union reported that there were “several schools for free negroes” in Nashville, and the paper saw no harm in their existence. However, after the November 1856 slave rebellion in Stewart County, the Nashville City Council passed a law outlawing schools for Black children.

Then there is the matter of assembly. In 1823, the Nashville Whig said it was the job of the local authorities was to “keep the streets clear of all assemblages of Negroes” — without specifying whether this meant just enslaved ones. In 1846, the Clarksville Weekly Chronicle said it was the duty of the town constable to disburse immediately any “unusual assemblage of negroes.”

In any case, the 1856 Nashville law that outlawed schools for Black children included this clear provision:

“There shall be no assemblage of negroes at any time after sundown for the purpose of attending preaching, and no free black or colored person, or slave, shall be permitted to act as a preacher to any assemblage of slaves; and no white man shall be permitted to preach to slaves or free negroes after night.”

All this begs the question: If free Black people in antebellum Tennessee couldn’t vote, choose any job that a white person could choose, have over for dinner who they wanted, marry who they chose, go on strike or go where they pleased, what could they do?

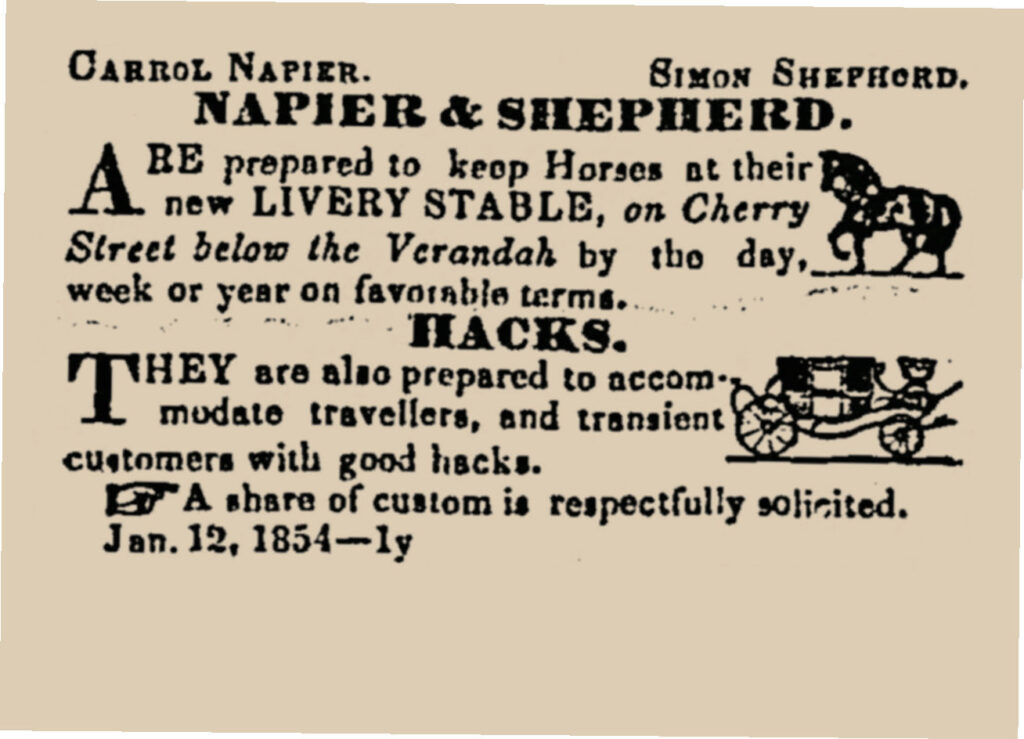

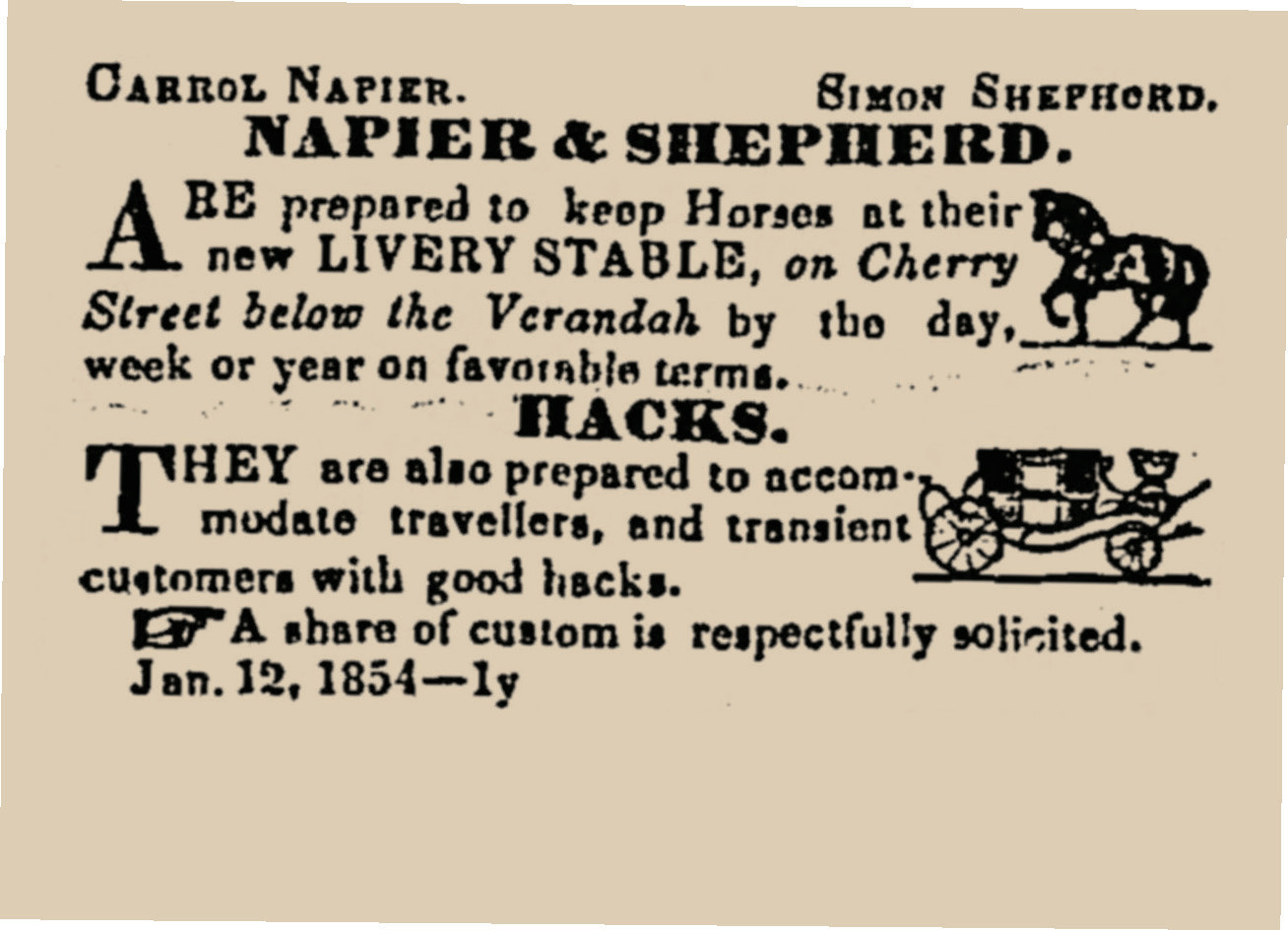

Free African-Americans could testify in court, and they could file lawsuits. They could attend church, during the day, with other free Black people — so long as the preacher didn’t speak against the institution of slavery. They could own certain types of businesses; among the prominent Black-owned businesses in Nashville were the caterer Sarah Estell and the livery stable Napier & Shepherd. Free Black people could own land. They could even own slaves (in fact, a free Black man in Rutherford County named Sherrod Bryant did own slaves)!

However, after studying Tennessee’s antebellum laws, I’ve concluded that “free persons of color” would have had a tendency to remain close to their domiciles, rarely gone out at night, avoided congregating publicly with other Black people and tried hard to remain on good terms with their local sheriff and county judge.

More than 100 years ago, a Tennessee historian named Douglas Anderson had this to say about the status of “free persons of color” in Tennessee before the Civil War: “Compared with slaves, the free Negro was a freeman. Compared with white men, he was not.”