In the heart of picturesque downtown Asheville, North Carolina, you will find a statue of a Tennessee-bred hog. Not a person, but a hog.

Why?

The story behind this amusing sculpture starts with geography. The French Broad River flows west from Asheville into Newport, Dandridge and Knoxville—creating a natural route into and out of Tennessee. In the 1800s, East Tennessee farmers herded livestock such as cattle, sheep, ducks, turkeys and hogs to slaughterhouses and trading marts in Asheville.

This statue in downtown Asheville is called “Crossroads: Turkeys and Pigs”

The road connecting Cocke County to Asheville became mainly associated with “hog drovers”—the term used for the men who herded hogs. It was not unusual for travelers on the French Broad Road to be forced aside on the road for 15 minutes or a half-hour to allow the noisy herds past. By the mid-1800s, when Tennessee was still known as the Hog and Hominy State, more than 80,000 hogs would be driven on this route.

Typically, this migration occurred in the late fall—after farmers had fattened their hogs with their surplus corn crop and before what was, and still is, known in agricultural circles as “hog killin’ time.”

Some of the stories and accounts of the hog drover era are quite humorous.

The 1851 Wilmington Daily Journal described the hog drovers of East Tennessee as a class of men who could perform incredible feats. “They are a species of human boa constrictor, never eating but once a day, and then swallowing at night from ten to sixteen cups of coffee, with biscuit and meat to match,” the paper reported. “We have met up in our time with some queer fish, but the East Tennessee hog-driver can take our hat.”

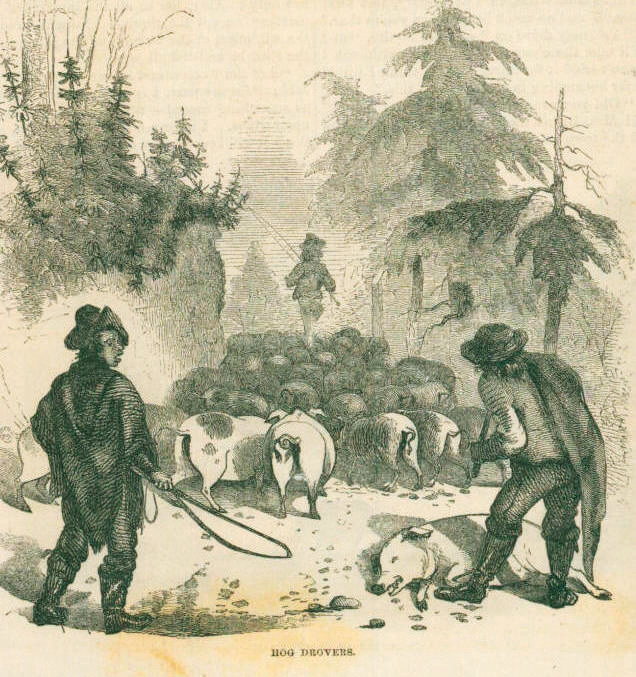

A sketch from Harper’s New Monthly Magazine in 1857 shows hog drovers in the French Broad Valley.

In 1878, the Winston-Salem People’s Press reported a verbal exchange that occurred in the courthouse in Marshall, North Carolina—one of the communities along the French Broad. Attempting to conduct court on a cold November day, a judge complained to a clerk about the noise from out-side the courtroom and told him to stop it.

“May it please your honor,” the clerk said, “it is impossible to stop that noise. It’s the hog-drovers.”

That same year, a traveler published his account of a journey down the French Broad Road in the Richmond Dispatch. “Hogs were before us and behind us, and both to the right and the left of us,” he wrote. “We were so constantly with them that we became critics of hogs. We became acquainted with each separate hog. We knew his movement, his color and his spots—nay, the very twist of his tail.”

Edmund Cody Burnett grew up in the French Broad Valley in the late 1800s and later wrote about his childhood. “As soon as a drove came through the gap in the ridge about a half mile distant across the river, we could hear the ‘ho-o-o-yuh! ho-o-o-yuh!’ of the drivers,” he wrote. “Sometimes we could hear the crack of their whips, both sounds increasing in volume at the schoolhouse as the drove drew nearer the ferry.”

This 1888 Rand McNally Map shows the road along the French Broad River.

Burnett said he spent many hours staring at the huge herds of hogs and their drivers: “Not every driver took pride in his voice, though some of them seemed eager to start the echoes from the nearby hillside, but every driver seemed proud of his whip.

“There is no room to doubt that a combination of the driver’s voice and whip impelled a lazy sluggish hog to quicken his pace.”

These drovers typically moved their herds about 10 miles a day and spent the night at roadside inns, often called wagon stands, with fenced-in areas for their livestock. Drovers would pay their bills with one of their hogs, then head out first thing in the morning after a big breakfast.

Wilma Dykeman devoted an entire chapter of her 1955 book “The French Broad” to the history and culture of the hog drovers. She wrote that each inn along the way had its own personality. “There was the Widow Frisbee’s where the sauerkraut dipped out of the wide, cloth-covered crocks had the finest flavor of any on the trip; and the Fletcher tavern at the little North Carolina village of that same name, where the proprietor, a man of wide variety, was a doctor serving his area day and night running his farm and tavern, too,” she wrote.

The French Broad River

“There was the Widow Patton’s, where apple brandy was manufactured at its government-licensed distillery, and a decanter called Black Betsy stood on the sideboard from which anyone might help himself free and welcome.”

So what happened to the culture of the hog drovers? It quickly vanished in the 1880s when railroads were completed from one end of the French Broad Valley to the other and gave farmers a less expensive way to send their livestock to market. The annual herds stopped coming through, the inns went out of business and the word “drover” slowly slipped from the local vernacular.