Historic photograph captures heyday of corporate giant

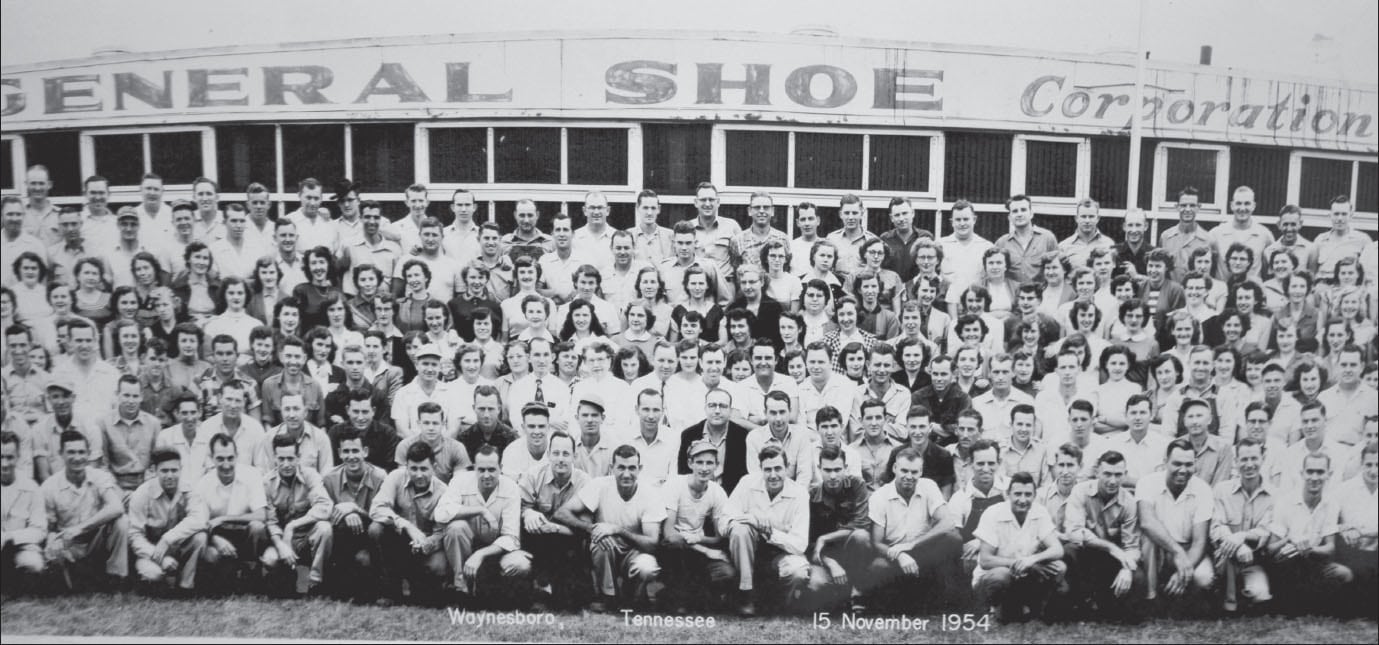

I recently had lunch at Emeralds, a restaurant beside the Wayne County Courthouse in Waynesboro. While there, I spotted a 1954 photo of employees of the local General Shoe factory. This reminded me of something I learned several years ago when I wrote a Nashville history book called “Fortunes, Fiddles and Fried Chicken.”

Genesco was, at one time, among Tennessee’s largest employers. At its peak in the 1960s, it had shoe factories all over the state, including Nashville, Gallatin, Tullahoma, Waynesboro, Hohenwald, Lewisburg, Pulaski, Cowan, Centerville, McMinnville, Camden and Smithville.

Genesco’s stock was, for nearly 40 years, one of the most reliable and profitable investments in America. Many Nashville families built wealth from 1930 through 1970 by owning shares of it.

Genesco was so big that it acquired other firms engaged in everything from making clothing and perfume to running variety stores. In fact, when the movie “Breakfast at Tiffany’s” came out, Genesco owned Tiffany’s!

However, Genesco’s revenues plummeted in the 1970s and 1980s. The company barely survived. Today, Genesco is a retail chain that owns stores such as Johnston & Murphy, Dockers Footwear and Journeys.

Genesco started in 1924 as the Jarman Shoe Company. One of the first lessons it learned was to not put a shoe factory too close to the Cumberland River; the first one the company built (in Nashville near the current site of Nissan Stadium) flooded and had to be replaced by one on higher ground.

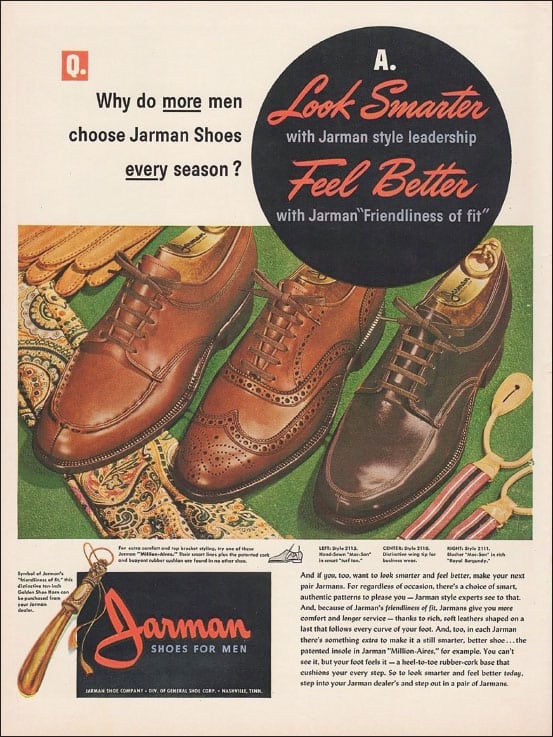

In Jarman Shoe’s early years, founders J.F. Jarman and William Weymss focused on making comfortable, long-lasting men’s dress shoes for as little money as possible. By 1930, the company had more than 1,000 employees producing 5,600 pairs of shoes per day at its main plant in Nashville.

Jarman Shoe specialized in the sale of “Friendly Fives” — $5 dress shoes that “could take a shine.” Within a few years, these shoes were available in stores all over the U.S. and advertised in national publications such as the Saturday Evening Post. Jarman Shoe even sponsored a radio show called “Friendly Five” on which a man named Friendly Fred tap-danced to the tunes of the Friendly Five Orchestra!

Jarman changed its name to General Shoe Corporation in 1933. It grew during the Great Depression, a time when most shoe and clothing manufacturers were shrinking or going out of business. Its executives (which included J.F. Jarman’s son, Maxey) worked tirelessly to produce a good shoe and sell it aggressively. One of the keys to the company’s success was the fact that labor costs were lower in the union-free South than they were in New England, which was where the shoe business had been centered.General Shoe made more than 5 million pairs of shoes and boots for the U.S. military during World War II. After the war, the company grew through acquisition. From 1950 until 1955, General Shoe acquired at least 18 shoe manufacturing, wholesaling and retailing businesses.

Among them were retail chains Berland (102 stores), W.L. Douglas (64 stores) and Nisley (46 stores). It also bought shoe-making firms such as Johnston & Murphy and I. Miller and Sons. These purchases of multiple parts of the industry terrified small shoe manufacturers. “If the big ones buy the retail chains, who’s going to buy our shoes?” an economist from the New England Shoe and Leather Association asked in 1951.

In 1955, the U.S. Justice Department filed an antitrust suit accusing General Shoe Corporation of trying to become a monopoly in the shoe business. The legal case caused the company to shift its focus from shoes to the apparel industry in general. Its new name: Genesco. Its new slogan: “Everything to wear.”

Hitting the ground running, the company bought the upscale department store chain Bonwit Teller (a purchase that included the jewelry store Tiffany’s). Genesco acquired a New York specialty shop called Henri Bendel, underwear manufacturer Formfit Rogers, men’s suit-maker L. Greif & Brothers, perfume-maker Parfum Givenchy, the variety store chain known as Kress and other companies.

The growth strategy was based on the optimistic notion that, as America got bigger, the acquisition of apparel manufacturers and retail chains would always work out in the end. This was, after all, the era of the American business conglomerate.

However, Genesco’s executives made several miscalculations (as did a lot of people in the apparel and shoe industry of that era). It did not foresee the “casual revolution” coming in the workplace. It completely missed the athletic shoe revolution started by Nike. But the biggest problem Genesco had was when shoe and apparel manufacturing shifted overseas in search of cheap labor — a process that dominated the last quarter of the 20th century.

“I remember the first time I said we should close some plants,” said Bill Wire, one of Genesco’s leaders in the 1980s. “The room just erupted. The company just did not want to recognize it. To me, it was like an ostrich with its head in the sand.”

Genesco eventually closed its manufacturing plants in places like Tullahoma, Gallatin and Waynesboro with devastating consequences to working people all over the state. By 1992, the apparel company that once had 65,000 employees had only about one-tenth of that number.

Today, Genesco no longer makes shoes; it contracts with manufacturers that make shoes in other countries around the world. The company has survived by repositioning itself as a retailer; today, it owns nearly 2,500 stores, including quite a few that operate in shopping malls across the U.S.

The General Shoe Corporation, whose employees are shown in the photo at Emeralds restaurant in Waynesboro, was nearly wiped out in the 1970s and 1980s by changes to American lifestyle and buying habits. Thankfully, Americans still buy shoes in stores. The shoe sales business hasn’t been wiped out like some other sectors of retail. Because of this, Genesco still exists and is even back in a growing mode.