The government of Memphis wants to dig up Nathan Bedford Forrest’s remains and move them to Elmwood Cemetery, which is where they were from the time of his death in 1877 until 1904.

This column will not talk about Forrest’s life, why his remains were moved in 1904 or why some people want them moved now. (Plenty has been written about these subjects in recent months.) But I would like to point out that he is not the only important person in Tennessee history whose grave has been moved.

John Sevier died in 1815 while taking part in a congressional delegation to establish a boundary between the United States and the Creek Indian Nation. He was buried near where he died, in present-day Macon County, Alabama, which is east of Montgomery. The remains of the first governor of Tennessee and the governor of the Lost State of Franklin remained there for 74 years before they were exhumed and moved to a spot beside the Knox County Courthouse.

James K. Polk died June 15, 1849, only 103 days after he left the presidency. For reasons I’ve never understood, he was first buried at Nashville City Cemetery. Within a year his remains were dug up and reburied in the front yard of Polk Place, his home in downtown Nashville. Then, in 1893, Polk was exhumed again so that his remains and those of his wife, Sarah Childress Polk, could be moved to the grounds of the Tennessee State Capitol.

I’ve always been curious about the movement of Sevier’s remains in 1889 and Polk’s four years later. I discovered recently that these two events are well documented.

Gordon Belt devoted quite a bit of space in his recent book “John Sevier: Tennessee’s First Hero” to the movement of Sevier’s remains. According to Belt, the key figure in arousing support to move Sevier’s remains was Arthur St. Clair Colyar, an industrialist and the author of a two-volume biography of Andrew Jackson. Colyar and the Tennessee Historical Society convinced the Tennessee General Assembly in 1889 to appropriate $500 to move Sevier’s remains from Alabama to a gravesite in Knoxville.

On June 17, 1889, an impressive group of dignitaries, including the governors of Alabama and Tennessee (Robert Love Taylor), gathered at Sevier’s grave in Alabama. After a few formal speeches were made, the crowd settled down and watched while two grave-diggers got to work.

I found an article about the event in the Knoxville Journal. What struck me about it were the details about what they found — and didn’t find — in Sevier’s grave. They didn’t find an ornate coffin — or a body. They did find a hollow place where the coffin had previously rested. Inside the hollow place was some soil that, upon further investigation by a professor from Auburn University, was declared to contain “disintegrated animal matter.” A while later, the gravediggers made more discoveries:

“The shovel brought up a whitish object covered with that peculiar substance noted on things undergoing what is termed dry-rot. Dr. Boyd took the object and pronounced it a piece of bone. The doctor examined it carefully and said that it was a portion of the thigh bone.”

Later, as they sifted through shovelfuls, they identified between 10 and 12 of Sevier’s teeth. All of these fragments were placed in a new casket and brought by train to Tennessee.

“As the train swept along through Cleveland, Charleston, Athens and other towns along the route, hundreds of people stood in silent reverence and in many instances with uncovered heads,” the article reported.

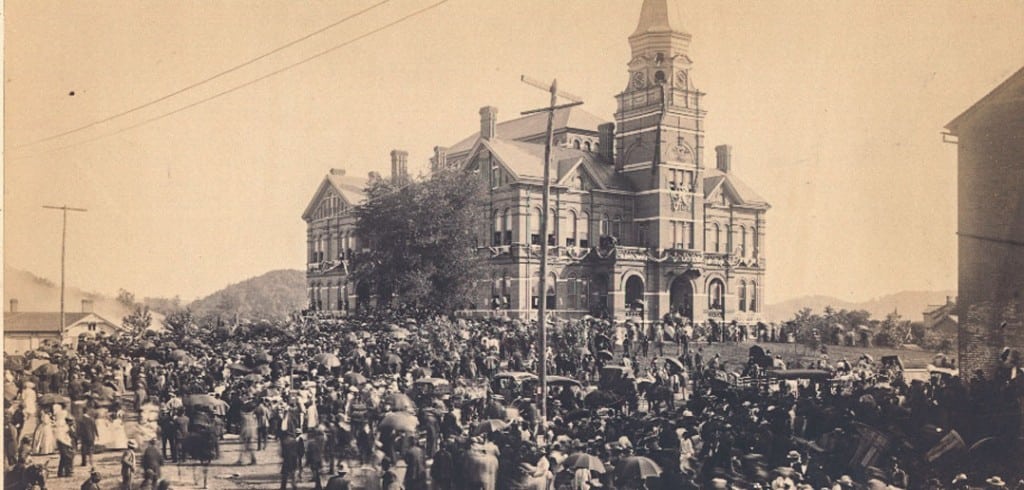

When the casket got to Knoxville, Sevier’s remains were reburied in a grave next to the Knox County Courthouse. The Tennessee State Library and Archives owns a photograph of Sevier’s second funeral, and the image is a testimony to how many people were interested in Tennessee history in the late 19th century.

The state of Tennessee decided to move Sevier’s remains to better honor the man. The decision to move Polk’s body originated from something entirely different.

You see, after Sarah Childress Polk died in 1891, the courts weren’t sure what to do with Polk’s assets because of the nature of the last will and testament of James K. Polk. In his will, Polk directed the state of Tennessee to care for the Polk Place mansion and the grounds around it, which included his and his wife’s graves. Polk made it clear that the state “shall not permit the same to be removed, nor any buildings or other improvements be placed or erected over the spot where said tomb may be.”

This may seem reasonable today, but this didn’t seem reasonable to Polk’s descendants at the time. In 1891, they challenged the legality of this will, saying they wanted his assets liquidated, divided and distributed. Since the will would have “established a perpetuity,” in legal terms, the courts declared it invalid. For the next several years there was a lot of hand-wringing about what to do with Polk Place.

The state of Tennessee nearly acquired Polk Place and made it the governor’s mansion (at the time, the governor stayed in a hotel room). But the General Assembly rejected that idea. In the meantime, on Sept. 19, 1893, the remains of the 11th president of the United States and his widow were dug up and moved to the Tennessee State Capitol.

In my mind, the reinterment of President and Mrs. Polk is one of the most disrespectful deeds ever committed by the state of Tennessee. I’m sure there were people who felt the same way at the time. However, the newspapers at the time didn’t reflect this point of view. “The services at Polk Place and Capitol Hill were very impressive, and the occasion was observed with due honor and respect by the state, the city, the church and the public,” the Nashville Banner reported.

Furthermore, unlike Sevier, the Polks were buried in copper caskets, and “both were in a perfect state of preservation,” so there was no need to search the graves for human remains.

After being placed on a plot northeast of the Tennessee State Capitol, the impressive monument over their graves was also moved and reassembled.

A few years after the Polks’ graves were removed, a developer named Craig McLenahan tore Polk Place down and built an apartment building there. Somewhere along the way, McLenahan donated part of the block to be developed into a Carnegie Library. I have read before that he did so to appease many Nashville residents who were sore at him for razing Polk’s home.

In any case, I am hopeful that the treatment of Sevier’s and Polk’s remains will put today’s debate about Nathan Bedford Forrest in some perspective. Truth is, we in Tennessee have a history of not letting famous people rest in peace.