They’ve been around for millions of years and have been supplying honey for the human race since the Stone Age, but there is great concern that their benefits to the world will be diminished, if not lost. However, with a little help from homeowners and other concerned citizens, there is hope for their future — and ours.

“They” are honeybees, those amazing and almost mythic creatures that possess a highly developed social structure and have helped sustain humankind and human society.

Once thought to be native to South Asia and the South East Asia subregion, more recent studies indicate that honeybees may also be native to Africa and probably to all continents except North America. Cave paintings and drawings also indicate that early on, humans recognized the value of honey.

As humans learned to domesticate honeybees, the art of beekeeping grew, and today honeybees provide us not just with honey but also with beeswax, propolis (a bee glue used in cosmetics and health supplements) and pollination services.

Though several species of honeybees exist, only two have been domesticated (the Egyptians were among the first to do so), and only one species (Apis mellifera) is used extensively for domestic honey production and pollination.

An average well-managed domestic hive will contain some 50,000 bees (sometimes as high as 80,000) during the peak of the midsummer season. Bees from that one hive can gather up to 80 pounds of pollen in a year and produce well in excess of 100 pounds of honey annually.

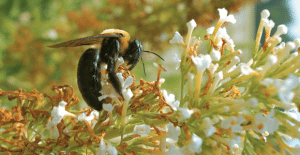

Honeybee species generally visit flowers to collect pollen, their source of protein, and in the process they are responsible for an estimated 80 percent of all insect pollination. This service is valued in the billions of dollars, and without it many commercial and homegrown food crops would be greatly reduced.

In 2007, honeybees made the news because a disturbing number (30 percent to 70 percent) of North American European honey bee hives collapsed. This sudden and unprecedented decline was named colony collapse disorder (CCD). So far researchers have not found a specific cause of CCD, though many scientists suspect it is a syndrome caused by a combination of factors rather than a single pathogen or poison.

Included among those factors may be loss of habitat, changes in agricultural practices, new viruses and pathogens, extreme weather during the past decade that resulted in impaired protein (pollen) production and the possible synergistic effects of any combination of these factors.

A decline in beekeeping, another contributing factor to the decline in honeybee population, has been taking place since the 1950s.

For many years the cause of decline was economic in nature and was tied to the availability of other sweeteners on the market. Access to inexpensive sugar and high fructose corn sugar (HFCS) changed consumers’ habits, causing many to stop using honey as a home sweetener.

With relatively cheap sweetener prices, we no longer consume much honey on a per-person basis — less than two pounds per year. On the other hand, we consume more than 100 pounds of refined sugars and HFCS per person, and some estimates are much higher than that.

This caused honey prices for many years to stay so low as to make it difficult to make a living, and many commercial beekeepers gave up their operations.

Compounding that problem are the health issues of honey bees. In the last 20 years we have had two new parasitic mites that have come into the country, and the varroa mite vectors as many as 17 to 20 different viruses that affect honey bee health. This has increased the cost of keeping bees alive, resulting in some beekeepers giving up this important work for jobs in other fields.

Without a corresponding rise in pollinating fees over the past 15 years or so, many of the larger beekeepers that are still in existence would likely have gone out of business as well.

Though current research indicates that the use of chemicals in home gardens and landscapes has not contributed to CCD, homeowners can still help protect these amazing and economically important creatures.

The main thing homeowners can do is provide plantings of beneficial flowers that bloom during the full season to provide nectar for honeybees and all native pollinators.

The second thing that can be done is educate the public to accept a lower level of perfection in their yards and gardens and use fewer herbicides and pesticides that can affect pollinators. It is not a good thing to treat our lawns to remove clovers and even dandelions that provide nectar to bees. While it makes for a less-than-perfect-looking lawn, it is more natural and beneficial to the bees.

White clovers and native wild flowers, trees and shrubs that provide lots of pollen and nectar are wonderful additions to yards and landscapes. Shrubs such as spirea, currents, blackberries, blueberries and even honeysuckle are great choices. Beneficial trees include all fruit-producing species and ornamental trees such as Bradford pears and black locusts.

Homeowners certainly can take up beekeeping themselves. Beekeeping courses are available in every state, often through local beekeeping associations and Extension programs. And if beekeeping is not feasible, homeowners can still help by providing locations for beekeepers to place bees, especially on the outskirts of towns and suburban environments but also in the countryside.

So what’s the course of action should a swarm of honeybees show up on its own? Because they can pose a threat to people and animals and because the swarm may be the more aggressive strain of Africanized honeybees, call a local beekeeper to have them removed.

To learn more about honeybees and beekeeping, visit the American Beekeeping Federation website, www.abfnet.org, or contact a county or regional Extension office for sources of local information and help.

Tim Tucker is a member of the American Beekeeping Federation’s Membership and Marketing Committee and editor of the organization’s E-Buzz newsletter.